HOPE GANGLOFF

“I started painting in earnest as soon as I could afford a larger studio,” laughs the artist Hope Gangloff. “Every time I can manage to, I move into a larger space.” The relatively recent transition back to painting, which occurred over the last several years after a protracted period during which she focused primarily on drawing, was a kind of homecoming for Gangloff, who grew up painting large-scale pieces in her parents’ barn on Long Island. “When I was much younger I painted really large,” she says. “I loved it. I love moving across a canvas, it feels good.”

This autumn, Gangloff will get an opportunity to return to her large-scale roots with a show at the Eli and Edythe Broad Museum at Michigan State University, where she’ll select pieces from the museum’s permanent collection to hang alongside works of her own, along with a new mural designed to activate the space. A show at the Kemper Museum in Kansas City will follow in October.

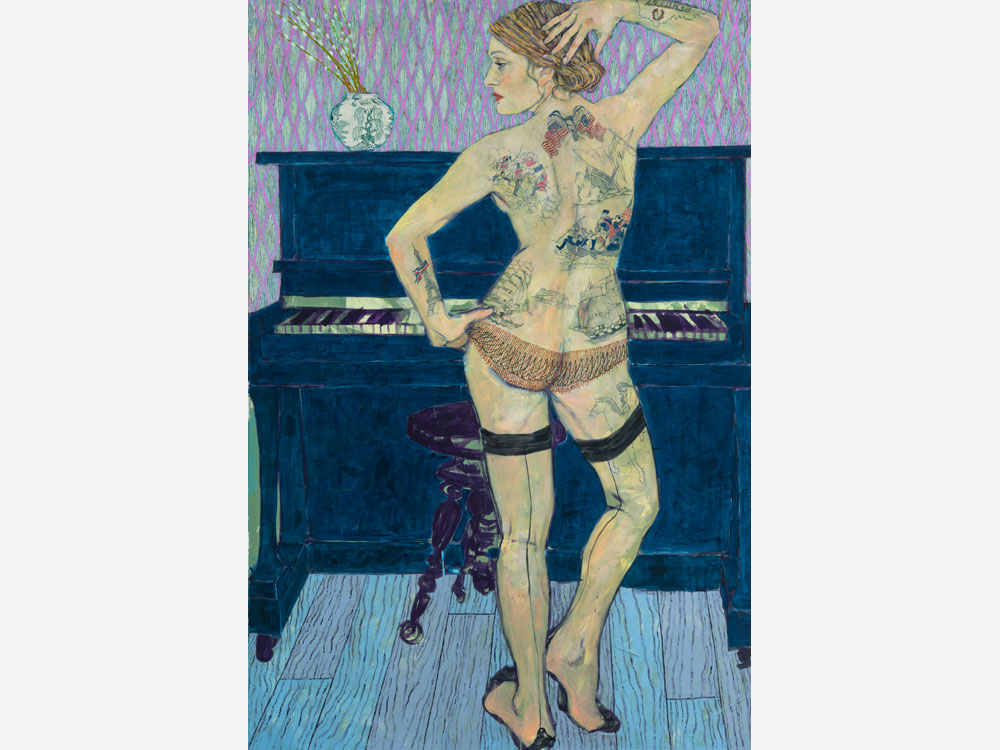

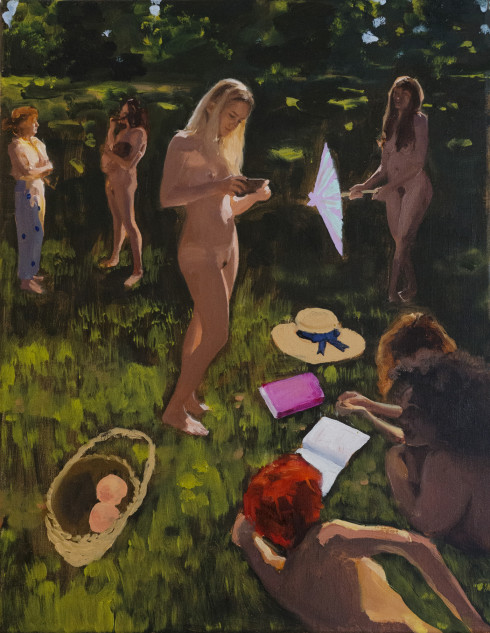

Gangloff came of age as a student at Cooper Union in the mid- Nineties, a time which is now much-mythologized as a boiling point for unfettered artistic creativity in New York City. It was at Cooper that Gangloff began training her eye on friends and acquaintances, creating portraits whose slight exaggerations and off-kilter compositions enhance the subjects’ likenesses. As the years have passed and her work has matured, Gangloff has benefited increasingly from patient subjects (both local and from points further afield) who arrive to sit for her in her studio, which is located in a converted factory a few hours north of New York City, and which she shares with her husband, the painter Benjamin Degen. “I really just use the sitting as an opportunity to get the lines down, then I just begin pushing paint around on the canvas,” Gangloff emphasizes. After she’s laid the foundation for the composition, she moves on to complete the painting in loose strokes, without meticulous concern for things like shadow or perspective. The results have a kind of pleasant flatness that recalls the symbolist canvases of Gustav Klimt and even the Post-Impressionism of Vincent van Gogh.

Gangloff herself, however, doesn’t find the comparison particularly germane. “I mean, who doesn’t like Van Gogh?” she notes. “He was very purposeful, and I like that. He knew what he was doing and it looks like fun.” A current of play and fun is very important to Gangloff; she emphasizes that joyful- ness is the quality in her work that she prizes above all others. As far as influences go, she’s not so concerned with venerated masters or the dusty annals of art history, preferring instead to take inspiration from her peers. “I like the duality of knowing the artist and knowing their art; it makes it more enjoyable for me to look at their work,” she says. Given that the subjects of her canvases tend to be friends and fellow artists, it makes perfect sense that Gangloff would find more meaning from personal relationships than history books or the hallowed halls of great museums.

For all her technical skill, there is a seductive humility to Gangloff’s work. For years, she has pursued dual practices; in addition to her painting, she is an active illustrator, creating images to accompany stories in The New Yorker, New York, and other publications. “I prefer to do opinion editorial pieces,” she says, noting that she frequently recasts friends in different roles to suit the story. “There are really only certain types of stories I’m interested in illustrating,” Gangloff notes. “No cigarette ads, no banks, no pharmaceutical companies. The New Yorker sent me to a play, and that was fun. Movie reviews are fun.” Gangloff believes illustration is an art that needs to be elevated. “A lot of the computer art that young illustrators come up with right out of school is really bad,” she laughs.

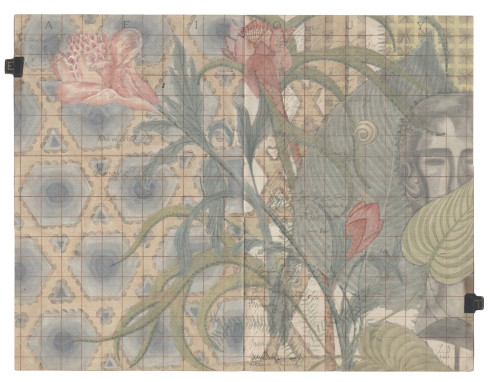

At a glance, Gangloff’s strength in drawing is plain in her paintings. Gangloff takes obvious delight in line and pattern, filling her compositions with quilts and textiles. “I love to sew,” Gangloff says, noting that “a lot of the quilts in my paintings are actual patterns I made for my husband.” Through Gangloff’s eyes, simple portraits of friends become beguiling collages that straddle the line between two and three dimensions, full of whimsy, physical presence, subtle elegance, and visual delight.

Despite the striking uniqueness of her style already, Gangloff is determined to keep evolving. There are “small, radical breaks in every painting,” she says. “It’s always new. If it ever feels mechanical, it’s time to stop or change directions.”

“Dressed Up,” a group exhibition featuring a selection of Gangloff’s paintings, runs through April 27, 2014, at the Kemper Museum of Contemporary Art, Kansas City, Missouri. All images courtesy of the artist and Susan Inglett Gallery, New York.

Kevin Greenberg is the art editor of The Last Magazine. He is also a practicing architect and the principal of Space Exploration, an integrated architecture and interior design firm located in New York. In addition to his work for The Last Magazine, Kevin is an editor of PIN-UP, a semi-annual “magazine for architectural entertainment.”