- By

- Karen Wong

- Photography by

- Iwan Baan

JUNYA ISHIGAMI

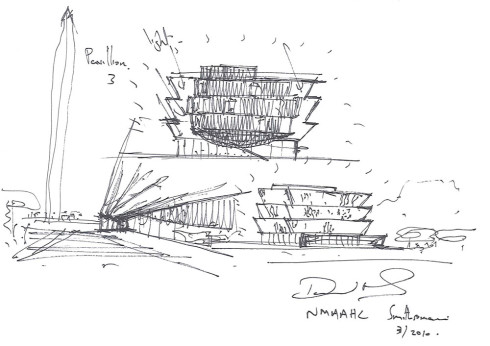

When other architects speak about Junya Ishigami, they use words like charming, ephemeral, poetic, fragile, and magical. They are not wrong. But that’s only half the story. After a four-year stint at the Tokyo studio of SANAA, Ishigami set up his own practice, Junya Ishigami and Associates, in 2004. He emerged onto the global stage in 2008 with three very different projects: a Yohji Yamamoto boutique in New York, a series of pavilions in Venice, and a maker space in his hometown of Kanagawa.

The Yamamoto store on Gansevoort Street, now home to Marni Edition, opened to great fanfare on an unusual triangular site in the Meatpacking District. Imagine a slice of pie with a path cut in it midsection, resulting in two discrete rooms and a passageway in between. This bold and highly original move upended the retail model by reducing selling space, providing a pedestrian shortcut between Gansevoort and 13th streets, siting an entrance that is hard to find (and very Japanese), and carving out large windows so natural light would highlight the enigmatic beauty of Yamamoto’s designs.

Tapped to reimagine the Japanese Pavilion at the Venice Architecture Biennale, Ishigami did the opposite. He left the building empty, with the exception of meticulous drawings rendered on the white walls in his trademark naïve style. Outside the modernist building in the surrounding garden stood eight small glass structures with a delicate framework of thin pillars. The eight cube greenhouses protected indigenous plants of Japan curated by an ikebana master. The interior was contemplative yet extreme. His studio spent superhuman hours on the expansive cartographic drawing depicting how this installation was conceptualized. Outside, he disrupted the existing landscape and imposed his architecture, and yet the entire exercise felt harmonious.

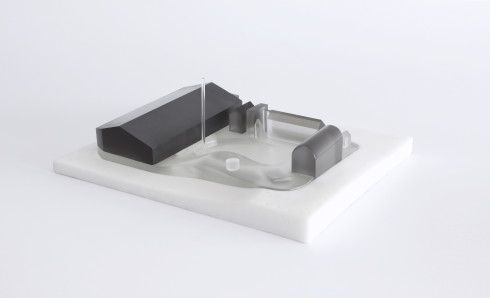

In the suburbs of Tokyo (a misnomer for a ninety-minute ride on the subway) is the Kanagawa Institute of Technology. There, Ishigami designed a 21,000-square-foot glass box otherwise known as the University Project Space. It is an incubator at the campus’ center, brimming with activity for all to see. The absence of walls leaves us instead with 305 barely perceptible steel-plate columns painted white. Forty-two columns are angled and positioned to carry the vertical loads. The other 263 columns carry the horizontal load. The arrangement maps out fourteen spaces for specialized activity, including pottery, woodworking, computer graphics, and metal casting, and a supply store and an office area for facility supervisors. Deceivingly simple and elegantly muscular, this project took three years of research and a thousand models.

One cannot deny the Narnian quality of the University Project Space, an enchanted white forest complete with potted plants and small trees dotting the landscape. The wafer-thin glass façade is rendered almost invisible, making us believe we have the power to walk through walls, like Kitty Pryde of X-Men.

More recently, Ishigami has continued to captivate with his Architecture as Air installations at the Arsenale in Venice in 2010, for which he won the Golden Lion, and the following year at the Barbican’s Curve Gallery in London. These controversial exhibitions consisted of thread-thin columns made from carbon fiber sheets that were braced by a cobweb of diagonals made of the same material. At first glance you saw nothing, and some detractors exclaimed this was a feat of the “emperor has no clothes” variety. Both these presentations were experiments in defining space for an actual building. The almost imperceptible lines were a three-dimensional drawing predicated on complex geometries and mathematics, reminding us that a lot of what happens in architecture is made invisible.

The architectural community has perhaps purposely positioned Ishigami’s work as precious and conceptual, resulting in a slower groove for larger-scale work. But in good time, Ishigami will prevail—recent competition wins for a ferry terminal in Taiwan and a significant visitor center for a park in the Netherlands will allow him to flex his muscles. In the poetry, there is technical prowess; in the fragility, there is sweat. Ishigami makes the public see what he wants it to see and uses artistry as his sleight of hand, making invisible the fundamentals of architecture that are so inherently pervasive in his work. So what is the full story? Ishigami is the magician.

“A Japanese Constellation: Toyo Ito, SANAA, and Beyond” runs through July 4 at the Museum of Modern Art, New York.

- By

- Karen Wong

- Photography by

- Iwan Baan