SHOOT

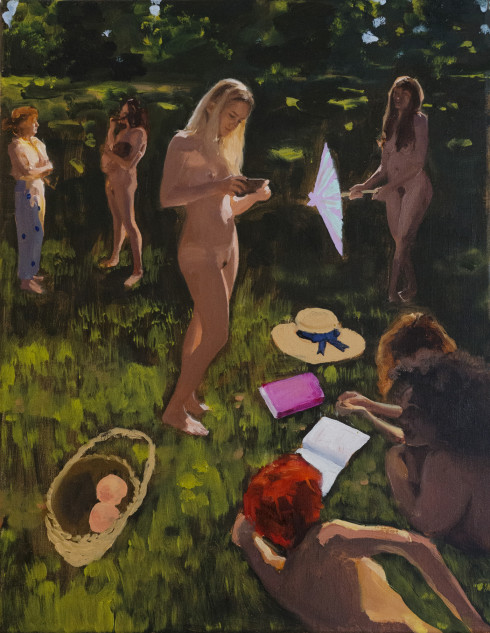

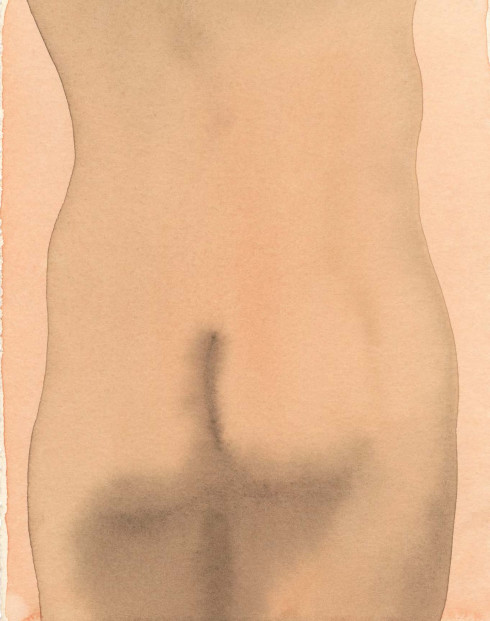

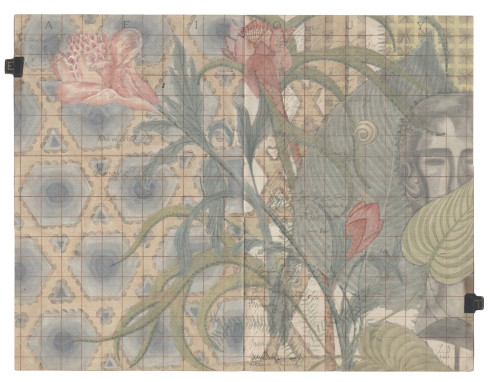

Newly published by Rizzoli, SHOOT: Photography of the Moment embraces a genre of lo-fi, “caught moment” photography that depends much more on the ecstatic promise of a well-timed shutter click than on the magic of pre- and post-production tinkering. Surveying the work of 26 photographers—from legends like Nan Goldin and Boris Mikhailov to younger artists like Gynnis McDaris and Ola Rindal—the book emphasizes the importance of this type of photography as a distinct genre formulated by iconic figures including Stephen Shore, Lee Friedlander, William Eggleston and Bruce Davidson. If, as theorist Roland Barthes stated, every photograph is about death, the caught moments in SHOOT are perhaps a smidgen less about death’s certainty than the glimmering flashes of living at its most exalted. Here, we speak to the book’s editor, Ken Miller.

Aimee Walleston: The premise of SHOOT is antithetical to the elaborately staged work of someone like Gregory Crewdson, and also opposite the highly composed, digitally altered work of photographers like Andreas Gursky. How would you parse the differences between these styles and the work of the artists you feature in SHOOT?

Ken Miller: I think they’re all a reaction to digital media. The work of Crewdson, Gursky, Lachapelle, etc. reflects how easy to process and manipulate images with digital technology. But with its emphasis on very expensive production and post-production, this approach is very exclusionary. In a way, it’s saying the image is important and has value because it was expensive and time consuming to make. The other approach is a reaction to how easy it is for us all to make and share photographs, and how much we have come to rely on those images to define ourselves. But if everyone can now take pictures (and if you don’t even need a camera to take a photograph anymore), how do you define who is a “photographer”? I think it’s really daring to embrace the democratic qualities of the photographic image and to seek out the uncommon qualities in seemingly ordinary photographs.

AW: In a way, this type of photography (particularly in the hands of Goldin or early Tillmans) equates to certain aspects of literary autobiography. Do you see a link between these, or a crossover?

KM: Ummm… No, not really. Well, I think the common aspect they have is that the work is edited before it is presented to the public, which is what separates a diary form an autobiography. Once you go through and edit which images you’re going to exhibit and publish, you’ve created a manufactured narrative. It’s something we all do now when we select images for our Facebook profiles, Flickr pages, Tumblr pages, etc. There’s a certain image of yourself that you want to present, even if it’s not really “true.”

AW: How did you select the artists and work in the book?

KM: To a large degree, I let them self-curate. I started with a small handful of people I knew I wanted to include, and then I asked them who else I should include and went from there. I’ll admit that I didn’t include everyone they suggested and not everyone I invited is in the book, but overall I think it was pretty democratic.

Photography by: Glynnis McDaris, self portrait 2005