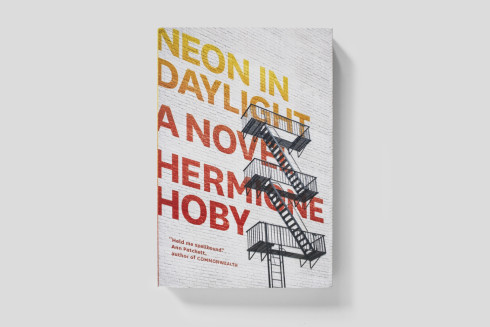

TEJU COLE'S 'EVERY DAY IS FOR THE THIEF'

“Every day is for the thief,” goes the Yoruba proverb, “but one day is for the owner.” Most often used to refer to embezzling politicians, it espouses the belief that you can lie, cheat, and steal, but no matter how long you get away with it, you will, someday, be caught. It trusts that justice will prevail.

The unnamed narrator in Teju Cole’s Every Day is for the Thief (technically his first book, as it was published in Nigeria before the Hemingway/PEN Award-winning Open City was released in America in 2011), who returns home to Lagos for the first time after fifteen years abroad, has a hard time believing it. In a series of vignettes, interspersed with Cole’s own melancholy photographs of the city, the narrator walks the reader through his reencounters with the venality and violence that permeate local daily life there, expressing his constant disappointment and wondering—doubting—whether he could ever return. He finds the streets papered with anti-corruption billboards as policemen extract “small gifts” from passing drivers. Young thugs known as “area boys” threaten their potential victims: “You have become wealthy and we must become wealthy too.” A child accused of theft is publicly burned alive in a marketplace, and Christian pastors drive Rolls Royces and own Learjets, insisting, “His true followers can be neither poor nor wretched.” The narrator reacts with outrage and disappointment, and then with weary acceptance.

It’s not easy for him to take in. Much like the narrator in Open City, he’s developed into an erudite sophisticate in the West, a lover of Coltrane and Ondaatje whose thoughts move freely from Marx to Chekhov to Beckett. A life in America and England “like a prince in exile” has spoiled him with “the assumptions of life in a Western democracy.” Nigeria, in comparison, is “a hostile environment for the life of the mind.” At first, the question of where he belongs hardly seems to warrant consideration.

Yet the place you belong is not always the place you call home, a thought that anchors the narrator’s meandering thoughts as he reacquaints himself with the city he left behind. He keeps returning to the uncertain space between his Nigerian past and American present, hoping to find himself there. In Lagos, however, he feels like a stranger; living abroad has changed him, perhaps irrevocably. Speaking in Yoruba to a market vendor, he is met with laughter and surprise, and then, irritated, wonders, “What subtle tells of dress or body language have, again, given me away?” He’s grown unable to conceal that he is tokumbo—Yoruba for ‘from over the seas’—and notes that this word, which was “once a mark of worldliness,” now has “a mildly pejorative air about it.” His narration carries a faint but noticeable current of underlying guilt—did I abandon them?—a feeling repatriates the world over never manage to shake.

Feeling alienated, he finds consolation in the like-minded few he encounters in Lagos, “the friendship of some powerful swimmers against the tide.” There is the enigmatic woman on the bus reading Ondaatje, the owners of a finely curated independent jazz shop, and the Musical Society of Nigeria, who are about to host a production of a play by Molière. “They are emerging, these creatives, in spite of everything,” he says, “and they are essential because they are the signs of hope in a place that, like all other places on the limited earth, needs hope.”

He can’t avoid the obvious question: could he not be one of those Lagosian creatives? He realizes that, although it’s the city’s chaos that deters him, it’s this same chaos that makes this city a writer’s paradise. Why should he, like Western writers, bother to “ply [his] trade from sleepy American suburbs, writing divorce scenes symbolized by the very slow washing of dishes,” when spontaneous brawls erupt and subside in the streets? Yet the oppression and heartbreak are still too much to bear. “I don’t care if there are a million untold stories,” he says. “I decide that I love my own tranquillity too much to muck about in other people’s troubles.” A paragraph later: “I am going to move back to Lagos. I must.” Lying in bed with his headphones on, Coltrane’s Giant Steps battles with the clamor of the electrical generators, and “Neither gives way.”

Home, the narrator muses, is “so simple a word, and so hard to pin its meaning.” It’s a big idea to explore, yet Cole does so conscientiously and succinctly through his spare, deliberate prose and his carefully curated scenes. There are no straightforward answers in Every Day Is for the Thief, there’s no obvious order to the vignettes, and there’s no real plot. Cole’s narrator is content to simply walk, allowing himself to get lost and ask more, not fewer, questions. In the final, poignant scene, he wanders the winding streets of Lagos until he comes across a community of carpenters dedicated to the timeworn tradition of housing the dead. He is moved by the honesty and purity of their work. “I sense an intentionality to my being there,” he says. “It feels like a return, like a center, though it is not a place I have ever been before.” It’s when he’s most disoriented that he comes closest to finding home, whatever it may be.

Every Day Is for the Thief is out now from Random House.

Yasmin Tayag is an editor and writer based in New York. She is occasionally a video host for Scientific American.