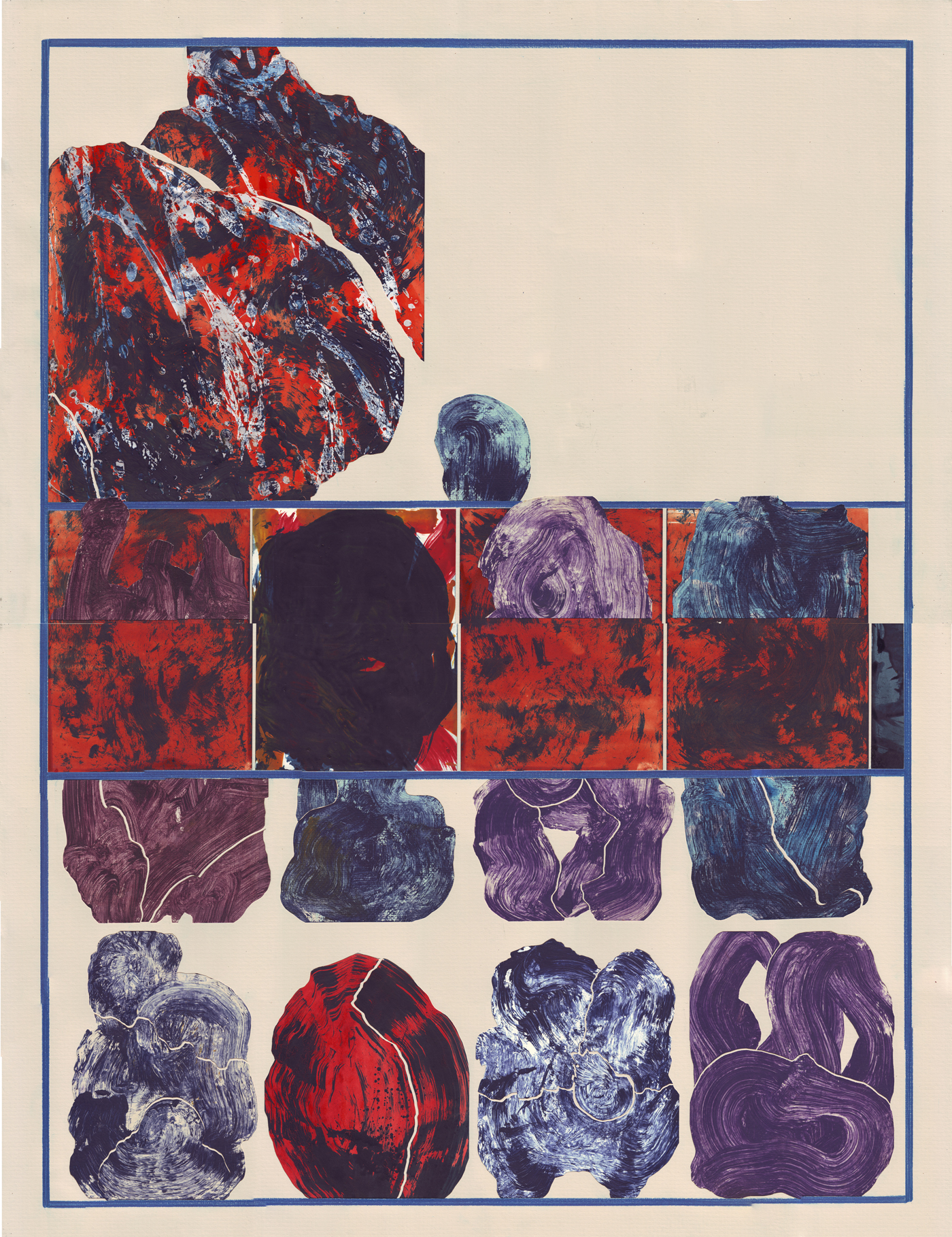

Chyrum Lambert, ‘New Career A Snake,’ 2016.

- By

- Kevin Greenberg

All images courtesy of the artist.

CHYRUM LAMBERT

“I’ve always been drawn to something that’s not quite there,” muses the artist Chyrum Lambert. “When it comes to how I approach a composition, what appeals to me is ambiguity: forms that hint distantly at figures or certain shapes without ever quite coming into focus.”

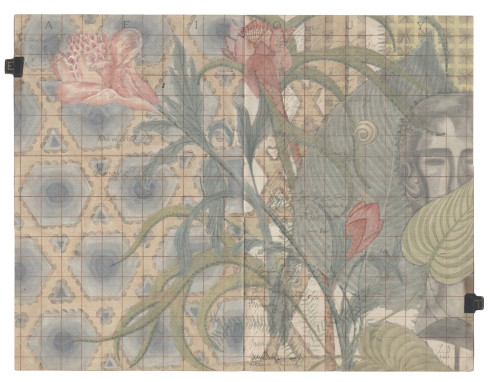

Lambert employs a complex process: working almost exclusively on paper, he begins with painting, focusing on brushwork and gestural expression; then he isolates whorls, eddies, and other organic shapes and cuts them away, assembling them into a collage alongside other materials, including patterned fabric and industrial abrasives.

The crisp edges and stark forms of Lambert’s finished paintings create a delightful balance between figuration and abstraction. Some pieces seem wide focus, long range—the dimples and knurls of Lambert’s brushwork suggesting the crags and peaks of a dramatic alien topography, framed by an impenetrable fog. Others seem to operate at a more intimate scale: here is a collection of small geological objects, there is a hooded figure skulking toward a placid sea.

“I’m super messy,” laughs Lambert, who lives in Los Angeles. “I paint in my backyard. I take what I’ve painted and I haul it down to the studio, cut things up, and animate them as I compose them.”

“I feel like I can grow most easily by working this way,” says the 36-year-old artist, noting that he’s been employing this technique for the past six or seven years. However, there’s more to his work than morphological noodling or academic compositional experiments.

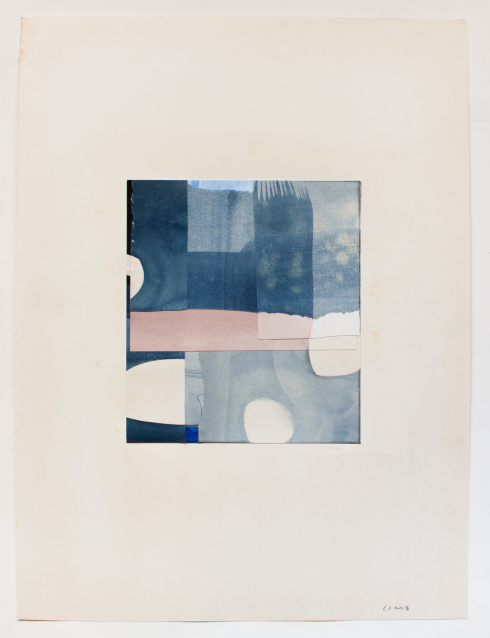

“In fact, I don’t think about shape. It’s about texture and tonal value,” he explains. “How do I affect the material I’m using— whether it’s wax or dye, or a textile, or sandpaper—to draw out its unique characteristics and achieve a heightened sense of color or combination of colors? I’m drawn to dynamic, high-contrast jumps in color. How can I take this pink and make it feel effortless next to this neon green, even if they wouldn’t normally work together?

“I also enjoy trying to surprise myself with unexpected adjacencies in the compositions,” he continues. “I know certain things will always work, but I kind of like to be surprised. I like a lot of negative space and spaces that shouldn’t be. I like grids and framing devices.”

Lambert works at various sizes and with different rectangular proportions as his backdrop. Often, he begins with a small five-inch-by-five-inch study. These pieces, which almost have the intimate, close-focus feeling of a tone poem, often originate from the huge piles of leftover painted scraps that are a byproduct of his process.

“Working at a dimension like that, the textures and scales of brushstrokes are very different than the larger compositions,” the artist notes. “It comes down to the viewing distance. That’s how the gridded pieces developed.” In the past, Lambert has created large compositions that present a regular grid of diverse five-inch-by-five-inch forms, starkly highlighted against negative space. The resulting pieces have the playful feel of an ad hoc taxonomy.

“It’s a way of revisiting and mentally cataloging my existing materials, but also about having all those images hit your eyes at once,” Lambert says. “I try to endow the larger pieces with a more pronounced focus or hierarchy. These small ones are less hierarchical.”

Lambert likes integrating fabric into his pieces because it’s less rigid, he says. He can glue it down, but “you can’t get a straight line, which I really like. The more you fiddle with it, the more movement it gets,” he smiles. Lambert goes to thrift stores and buys different bedsheets to use in his work. The fact that he’s likely to never encounter the same pattern twice appeals to him. “It’s fresh and surprising. I can’t anticipate before I begin the work what type of look I’m likely to get with that particular texture or pattern or weight of fabric,” he says. “The way fabric captures light is really nice compared to paper. It’s kind of a nice jump.”

Nevertheless, Lambert does have favorite materials, and one of them is the cream-hued paper stock upon which he creates his compositions, and which has become a signature element of his work. The bone-colored background, often preserved in vast expanses of negative space, lends his pieces a pleasingly vintage look, though Lambert is quick to point out his preference for the material has nothing to do with creating the appearance of age. “I simply want to be able to use white as a foreground color as well,” he explains.

Despite his mixed-media approach, Lambert shies away from being labeled as a collage artist. “I still feel like I’m a painter,” he asserts, adding that two of his favorite artists are the painters Richard Diebenkorn and RB Kitaj.

For a brief period, Lambert employed text in his compositions, but he admits it only added to the notion that his primary interest was collage. “I want my paintings to feel unsure of themselves in a way,” he notes. “The presence of text is hard because it’s declaring something.”

Still, he wants people to know the title of the works they’re viewing. To Lambert, an avid reader of poetry, a considered title creates a more viable interplay between word and image. “I like to use the title to tilt things in a certain direction a little bit,” he grins.

In practice, Lambert’s associative titling technique bears fruit: without knowing the title of Empty Chair, Table, Dinner (2016), a viewer might not be inclined to read the broad and slender rectangle dotted with vaguely round forms and surrounded by ergonomic voids as a bird’s-eye view of the titular meal. But once you’ve heard the work’s name, it’s hard to see it any other way.

There’s a charmingly mischievous quality to Lambert, both in his work and in the way he talks about it. “I’ve always been rebellious, and kind of anti-schooling,” he says quietly. “I’ve always been more of a hands-on type of person.”

In lieu of attending art school, Lambert spent his formative years traveling the West Coast, writing, making art, and playing music in his spare time. He doesn’t regret his lack of formal training. “To me, the joy of learning is about making small personal discoveries,” he says. “I had to be self-disciplined about getting better at things.”

After twenty years of regular work, painting is an integral part of his daily routine, no matter where he finds himself or what else is happening in his life. It’s automatic. “I come down to work every day just because I’ve been doing it every day since I was in my twenties,” he says. “I can be dead tired, but I just enjoy doing it.”

- By

- Kevin Greenberg

All images courtesy of the artist.