COMPASSION

Living forever at the crossroads of Canadian and amazing, artist and curator AA Bronson is New York’s answer to a conceptual art soothsayer and savior. Originally a member of the art collective General Idea, Bronson’s practice has always pushed the boundaries of art to its spacial and spiritual limits, and continues to do so. While other people are staging outlaw art exhibitions in salon-style environments and disused commercial spaces, Bronson is currently exhibiting an immaculate collection of artworks—by Marina Abramović, Bas Jan Ader and Scott Treleaven, among others, and themed around the idea of “Compassion”—in a seminary. The visually astounding Union Theological Seminary, to be exact. Created in conjunction with the newly-formed Institute for Art, Religion and Social Justice, the show will be on view until December 19th. Here we speak to Bronson about the organization and the show’s premise.

Aimee Walleston: Your practice, both as an artist and a curator, has often been linked to creating and distributing art beyond the confines of the museum or gallery space. Why did you decide to have this show at the seminary?

AA Bronson: I began studying at Union Theological Seminary a little over a year ago. For the last years, Union, like many seminaries, has been very shut off from the world, and almost no one I know has seen the inside of this quite amazing complex. As much as anything, the exhibition was a way to open Union’s doors, and get people moving through the spaces, to give some awareness of what is there, both architecturally and in terms of its resources, such as the extraordinary library. At the same time, I wanted to bring people’s awareness to the ways in which art addresses “spiritual” issues. None of the artists in the exhibition would be considered out of the usual in the Chelsea art world, but by framing their work in the context of the word “compassion”, and a “pilgrimage” through a seminary, other aspects of the work begin to leak out, the work is enriched by the context, and vice versa.

AW: Can you explain a bit about the Institute for Art, Religion and Social Justice, and your involvement with it?

AB: Union is known for its involvement with social justice issues, and all seminaries include some relation to the arts in their program. However, I noted that nobody at the seminary had any idea of the massive amount of activity, especially amongst younger artists, in the contemporary art world related to social justice. Creative Time’s recent summit, “Revolutions in Social Practice” is a case in point. I proposed to the President of Union that we should found the Institute of Art, Religion, and Social Justice to facilitate some sort of conversation between the worlds of art and religion and she immediately agreed, making me the Artistic Director. At the moment we have only two projects, the exhibition “compassion,” and a series of dinners in which we bring together artists and theologians for mutual benefit.

AW: Spirituality is not something broadly discussed in artistic practice anymore. Your interests have often involved shamanism and less organized methods of spiritual practice. How do you see organized religion in regard to contemporary art practice?

AB: Organized religion does not interest me, per se. And at any rate, who is to say what is “organized” and what is not. Religion exists in so many hybridized forms today, and even the most conservative Roman Catholic is liable to be studying yoga on the side. Union is a non-denominational Christian seminary that is making rapid strides toward becoming multi-faith. Two of the professors are both Christian and Buddhist, and there is a number of Buddhist students, many Unitarians, a Quaker or two, and even an occasional agnostic. My own background is in Tibetan Buddhism, which I practiced for fourteen years; and, yes, I am also interested in shamanism and spiritualism, as well as voodoo and other African diaspora religions. The exhibition includes both Hindu and Buddhist forms, although the majority of the works are more “spiritual” than they are religious. I think that the intersection between art and religion can be seen through the lens of social justice, and social justice is a theme that is occupying many young artists today, especially the more radical collaborative practices, such as LTTR, Red76, or the Center for Tactical Magic.

AW: For whatever reason, compassion seems to be a tall order to ask of people. In relation to images that are meant to evoke compassion, like war images, where do you think contemporary art stands? And how does compassion relate to passion?

AB: Compassion has always been and will always be a tall order. As the world becomes more complex and more difficult, I see an increasing interest in compassion rather than a decrease. Alfredo Jaar’s Rwanda works, for example, address genocide in sometimes very explicit forms, while Yoko Ono’s Imagine Peace projects come at compassion from the opposite direction. The popularity of the Dalai Lama, whose primary message is compassion, speaks to our need in today’s world. As for passion, that is a more complex question. The word comes from the Latin for suffer or endure, but the Passion of Christ is clearly not what you are referring to here!

Union Theological Seminary

3041 Broadway at 121st Street

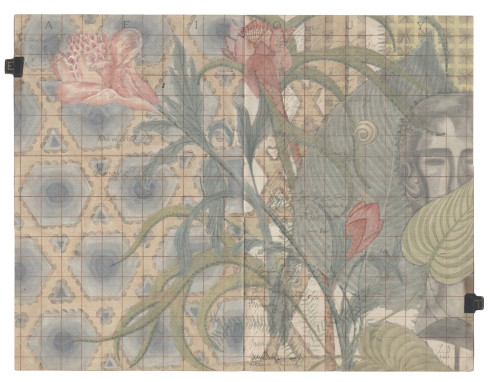

Chrysanne Stathacos

Rose Mandala Mirror (three reflections for HHDL), 2006

Glass, mirror, roses

Dimensions variable

Courtesy the artist, New York