FROM THE ARCHIVE: FRANK HAINES, FALL 2009

We’ve been around awhile now, and we know a lot of our readers might not have had the opportunity to experience our earlier issues. So we wanted to give you the chance to discover one of our favorite stories from our archive every Friday. Some of them feature actors, musicians, or artists who eventually made it big, talents we are proud to have tapped early in their careers. Some have brilliant writing, and some have beautiful photography. Some have both. But all of them are so great we thought they deserved a second chance. This week we present Aimee Walleston’s Fall 2009 profile of the satanically brilliant multi-talented artist Frank Haines.

ARTIST FRANK HAINES ISN’T AFRAID OF WHERE THE PRODUCTION AND SPECTACLE OF ART MIGHT LEAD HIM. HE MIXES MEDIA AND OCCULT REFERENCES AND KNOWS THAT AT THE END OF THE DAY, ART IS ABOUT THE EXPERIENCE. WHICH IS OBVIOUS FROM HIS TOTALLY TWISTED GALLERY PERFORMANCES.

“A work of art is a form that articulates forces, making them intelligible,” wrote critic Guy Davenport. And were he around today, Davenport could have easily created that chewy little line to describe American artist Frank Haines. Haines is a force and form unto himself: prone, kinetic body covered in tattoos, head crowned with prematurely pewter hair—and a mind packed tight with ruminations on artistic practice that are almost exasperatingly compelling. In his work, Haines adroitly hopscotches through myriad mediums—he is a musician, sculptor, and painter, among other things. But the conceptual underpinnings of his art always relate back to the simple necessity of making objects and events that articulate creative and spiritual thought. Equally, Haines employs a rigorous DIY sensibility in his work, ensuring that the art he makes is always an extension of the hand of its maker. At the Lisa Cooley gallery for the opening of his recent solo show, “Form Is the Graveyard of Consciousness,” Haines was selling the show’s self-made sound track, a creepy, evocative recording of experimental audio intrigue. Eschewing the tyranny and expectation of iTunes, Haines made his recording on cassette tape.

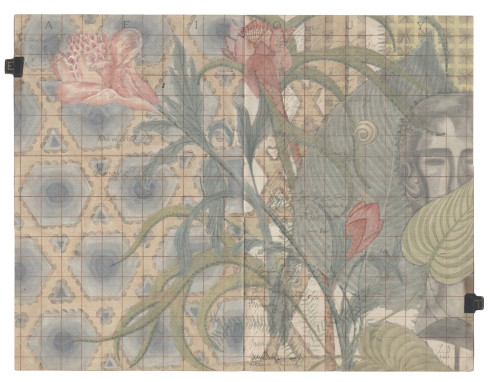

This decidedly analog, American punk ethos can be found in every nook and cranny of Haines’ world—he is 24/7 creator, and his life is based around his artistic practice in a way that rivals a Beuys or a Burden. Crammed with pagan-tinged ephemera, and presided over by an enormous feline emissary (Buddy), Haines’ small studio in Brooklyn is presently where the artist makes his work. Visiting, one has the feeling of entering an establishment where bands have probably crashed on the floor, and those who did were more than likely thankful for the graciousness of Haines’ “what’s mine is yours” mentality. Originally from Florida, Haines still carries with him a hint of the Sunshine State’s eerie feeling of paradise lost. Peel the orange and find the fruit rotten. Then make art out of it. He got his MFA from San Francisco State University and soon after began creating performance-based works which nodded to the campy supernaturalism of legendary filmmaker Kenneth Anger.

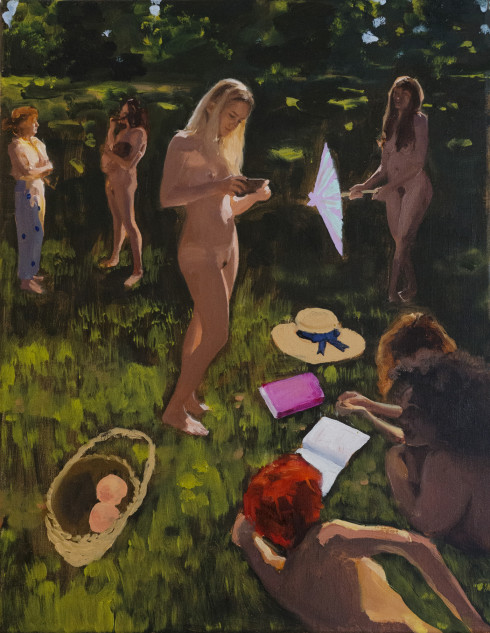

Anger is still a big influence (a presiding godfather in a way), as are the occultist symbols, ritual devices, and ceremonial motifs invoked in his films. This past summer, Haines organized an event at PS1 in New York to celebrate both the summer solstice and Anger’s retrospective at the museum. The event featured performances by several art world luminaries and also included a set by Haines’s band, Blanko & Noiry. Blanko & Noiry were first envisioned by Haines when he decided, on Good Friday (symbolic days are important) to contact a gentleman named Chris Kachulis. Kachulis, who is elderly, was once a collaborator and business manager of electronic music pioneer Bruce Haack (Haack’s 1970 recording Electric Lucifer was written in part by Kachulis and also features his vocals). Kachulis was responsible for bringing Haack’s music into more commercial venues, but has since been limelight-free and enjoying a quiet, 48-year career at ABC Studios in New York. On the basis of the Electric Lucifer recording and presumably a few other metaphysical impulses, Haines felt the stirrings of a creative union with Kachulis, and thus Blanko & Noiry was wrought. The team’s performances are spectacles to say the least, with music that spans the sonic landscape from industrial noise to vaudevillian oom-pah. The aesthetics of the team are similar to what Haines does on his own (i.e. lots of glam, glitter, and spewing paint, met with worship-ready iconography) and unite with the actionist artistic movement of post-war Vienna, where Haines recently spent his winter months.

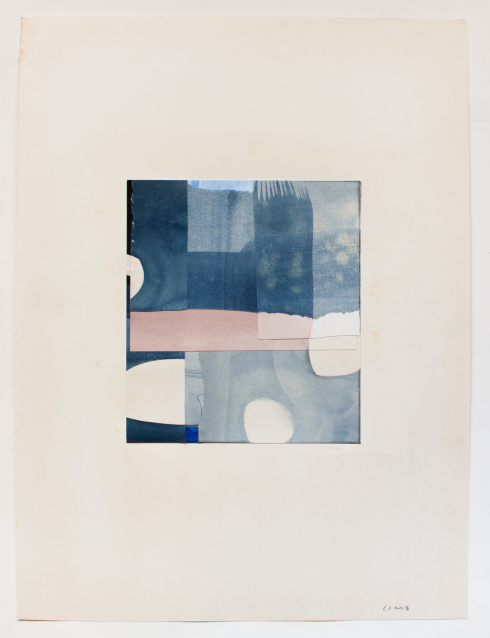

Like his performance pieces, much of Haines’ sculptural work and paintings harken to the artifact and language of ancient ritual—but these pieces are often transmogrified by the tenets and traditions of art history. One sees riffs on minimalism and Francis Bacon-esque abstraction in his work, much of which combines organic shapes with more geometric elements. His exploration into aesthetic form has as its basis a deep, somewhat Platonic interest in forms writ large: how they work in magic and religious ritual, and how those kinds of forms then reflect back onto society in the quotidian shapes and ideas that attack our retinas and cognition. To say Haines is a connoisseur of spirituality is to say that God sometimes likes to be in charge of things.

When questioned about belief and whether or not all his dutiful studies into the intricacies of spiritual practice are intellectual curiosities or firmly-held personal ideologies, Haines is caught in a moment of reflection. His honest answer seems to be that it’s an open question, which precisely mirrors his artistic practice. When Haines shows you his art, he wants you to take it on your own terms and he wants you to incorporate it into your life in your own way. Many artists aren’t like that. Many have a conceptual agenda or dogma that they feel is integral to a viewer’s experience. If you don’t hop the conceptual train with them, you are not getting it. But Haines seems to believe more in the formal aesthetics and experience of his objects, and that the “trip” (his oft-used word) they take you on is the endgame of his practice. Objects and events are never what they really are. They are always the moment you experience them: on your own, in a gallery; with the woman you love; with the man who’ll break your heart. Those things cannot be divorced from the experience of art. Art is always only memories.