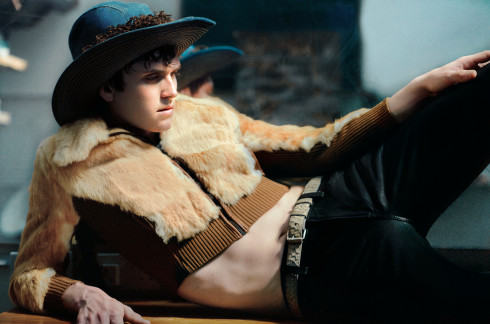

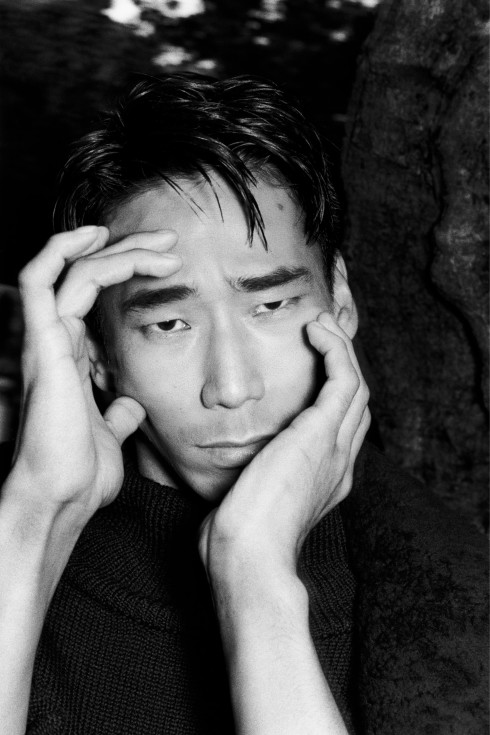

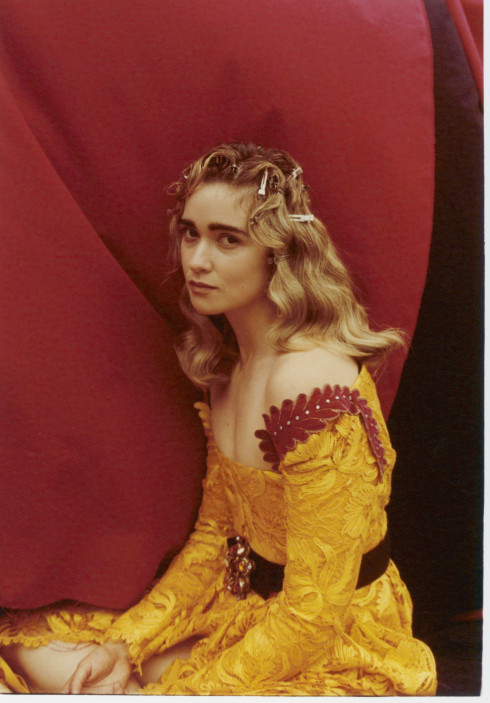

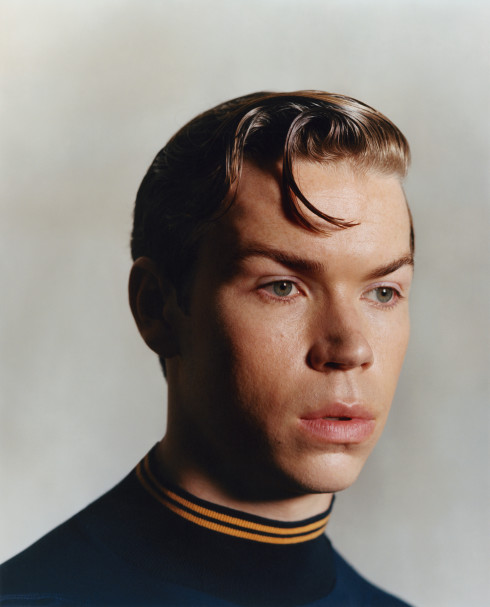

Photography by Hector Perez.

JACQUES NAUDE'S FIRST SHORT FILM

‘How often I have awoken here,’ an old man ponders, as he saunters through a sparse field, with the sun beating down on him. No one is around him, but life surrounds him, as arid as it may appear. It’s a setting that features a visually arresting, if somber, landscape featuring a character that is dignified in his isolation. The atmosphere is captivating, but in an unreal way, like a fantasy created just for a film. “I wanted to shoot this so you can almost picture this as being anywhere else in the world,” director Jacques Naude says about his first short film. If not for the Afrikaans dialect used in the carefully paced soliloquy, this might be any quiet countryside. But everything about “Overberg,” both the film and the region, leads the way for reflection, contrast, and a pensive inspection of life. “I wanted it to feel like a dream—and ultimately it is a dream.”

“Overberg” is a bold foray into the narrative film form, but Naude felt it was necessary to push himself creatively after years working in advertising and high-end fashion. When his friend Jimmy Traboulsi offered him an opportunity to create a short in South Africa, Overberg was a natural starting point: “Geographically it’s a very special place. It’s a place that’s close to my heart, it’s a place I grew up seeing and experiencing as a child, but it’s one of the most beautiful hidden areas of South Africa.” Raised in Capetown, Naude enjoyed big-city life, but it was always juxtaposed with country experiences he relished at his grandfather’s farm, where “Overberg” was filmed. “[The scenes] are small snippets of experiences that I had as a child in the farm, so a lot of it indirectly reflects my childhood, or things that I saw growing up.”

Contemplation is the underlying theme in “Overberg,” which runs just under seven minutes. In that span of time, Naude delivers an acute meditation on the acceptance of age. “Growing up, I was influenced a lot by my elders. My folks, my grandparents, I was always surrounded by a lot of…wisdom, if you want to call it that,” he says. “And I was always interested in life after death, and the present moment for us all; getting older and looking back on our past.” In the film, the old man takes a seat on a bench, alone in the vast expanse of his farm, and slowly drifts off into sleep. It’s in that state that he confronts his past, neither in conflict nor in longing, but in acceptance that his was a life that was lived.

Having a strong connection to his childhood surroundings allowed Naude to create a serene setting that fosters reflection, but the land itself plays a larger role in understanding the characters. “Growing up in Capetown, it’s a very cosmopolitan city in terms of culture and people,” he explains. “But we’ve got the nature element, we’re surrounded by really beautiful landscapes and mountains. There’s just so many different getaways to explore, and that’s obviously a massive influence for me, visually.”

His strong visual sense is used to great effect in “Overberg” to communicate the inextricable relationship between man and nature. “I feel like the film reflects the simplicity I see in life. The city is this crazy concrete jungle, and the getaways we go to are actually the type of lifestyle that these people live, everyday life,” he says. “We live in the surroundings we put ourselves in. I wanted to show these people that live on this land, and the type of life they live. And this is what they can reflect back on.”

The environment itself is a point that he’s focused on, as the beautiful visuals of canola fields and mountainous landscapes are intertwined with the characters’s existence. “You go through life in a certain area, and a lot of people don’t even get the chance to leave and to go see the rest of the world,” Naude muses. “But that [place] itself, to us that might look like heaven. It’s like heaven on earth, but that to them is just life. It’s like they live this really simple life, but the surroundings, the beauty they’re surrounded by, is almost a gift in itself.”

All of this is expressed without dialogue, but rather with a poetic narration that amplifies the intended effect. “We drew on old Afrikaans,” Naude says. “There are a lot of small innuendos and mannerisms within Afrikaans poetry. It’s a different language, because you can say one line that means a lot. There’s a lot of meaning in a lot of words in Afrikaans that can take the mind in many different directions.”

The complete film uses all of these elements in conjunction, resulting in something more coherent than you might expect from a first time filmmaker, carefully blurring the line between fiction and reality that Naude likes to focus on. That balance makes “Overberg” a sharp and promising entry, and it’s only in his description of his two characters that Naude reveals his own character as a filmmaker: “I wanted the little boy and this old man to have this connection of being dreamers. You get certain people that are naturally dreamers—they like to let their minds go.”

“Overberg” premieres tonight at Anthology Film Archives, New York.

Photography by Hector Perez.