- By

- Karen Wong

LEONG LEONG AT THE VENICE ARCHITECTURE BIENNALE

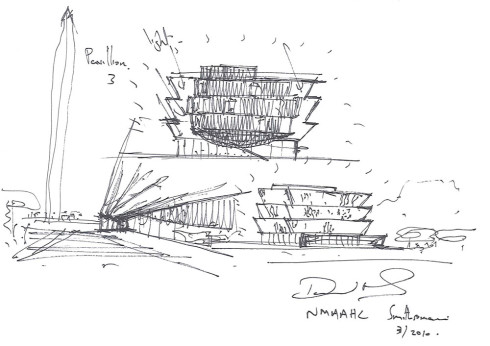

Less glamorous with less money and less crowds, the Venice Architecture Biennale is the ugly stepsister to the Art Biennale’s Cinderella held in alternating years. There were anxious expectations for Rem Koolhaas, author of the seminal Delirious New York and founder of the far reaching and influential office OMA, who was tapped to take the helm and set things right. Critics have applauded his encyclopedic “Fundamentals” exhibition that resides in the Central Pavilion in the Giardini, as well as his autocratic decision to steer all the national pavilions to focus on the rise of modernism over the last hundred years. A commanding commissioner, Koolhaas has organized one of the most cohesive biennales in recent memory. Standouts included the Korean Pavilion, whose attempt to bridge North and South Korea through architecture garnered the Golden Lion, and the clever and funny Russian Pavilion as an international trade fair promoting the modernization efforts of its motherland.

Closer to home, the US Pavilion, entitled OfficeUS, was brilliantly conceived by Eva Franch (Storefront for Art and Architecture), Ana Miljački (MIT), and Ashley Schafer (Praxis journal). The ambitious task of gathering and presenting a thousand projects built on foreign soil but designed by a hundred US-based firms, constituting the exportation of American modernism, was coupled by extending the exhibition model to double as a working office for the duration of the six-month run where Fellows would analyze and remake these projects in a contemporary context.

Making all these layers legible is the New York architecture studio Leong Leong Architecture, the brotherly duo of Chris and Dominic. The fashion community tapped them early on for their ability to negotiate surface, beauty, and materiality, and now, finally, the architectural world has the chance to see a powerful demonstration of their abilities in the refined makeover of the American pavilion through the end of November.

Karen Wong: Rem Koolhaas’ Biennale centers on a title and thesis, “Fundamentals,” as in ceiling, floor, windows, stairs, walls, roof, toilets, etc. Missing in his index is furniture. And yet the table that you designed for the OfficeUS is the cornerstone that organizes the exhibition/workspace. How would you explain this omission?

Chris and Dominic Leong: Well, it’s impossible to speak for Rem Koolhaas, but I do think that his strong “anti-design” polemic would have to exclude furniture since oftentimes it’s the only element within a building that could be considered a “design” object. Or maybe the exclusion of furniture is much more practical—the topic is just too broad to be tackled in an already expansive curatorial agenda. While it wasn’t a core part of the “Fundamentals” exhibition, furniture was an essential element for us to address when thinking about workspace and office culture. The evolution of office culture can be tracked by the genealogy of its furniture systems. From singular desks to concepts of the “office landscape” and now the presence of domestic or leisure furniture, the ideology of an office always manifests in its furniture design or selection.

Leong Leong has thus far built a reputation for innovation and elegance in the retail projects for 3.1 Phillip Lim. In these cases, your spaces are designed as a backdrop to Lim’s collections. Did you feel additional pressure or change your approach in the task of exhibition design for OfficeUS?

The common denominator between exhibition and retail design are the issues of display and desire. So in a conceptual sense, the main differences are only the content and the context. The pressure is the same, although in a store the audience experiences the environment in a state of distraction or as a background, while in an exhibition context, the design is more of an interface and is scrutinized much more. In both cases, the constraints are demanding while the expectations are still very high.

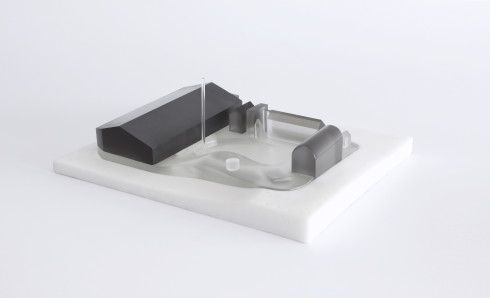

Your obsession with surfaces is a show-stopping counterpoint to the Neo-Palladian architecture of the US Pavilion. There’s the terrazzo foam cubes for seating, the smoky gray Plexiglas tabletop, the silver mylar blinds that veil the façade of the building. Talk me through these choices.

We were interested in the tension between banality and strangeness. We wanted to make an “office” that felt both very familiar and also a bit foreign by translating or abstracting certain cliches of modernism into an experience. The choice of materials was based on heightening this tension and altering the perception of the existing pavilion. For example, the foam cubes are very ambiguous. They look hard like the terrazzo floor but are actually very soft and comfortable. The mylar blinds are a very common window shading system, but when used so relentlessly, they create a blurry reflective surface like a Gerhard Richter painting. The table appears as if it extends beyond the walls of the pavilion as it’s reflected in the mirrored walls, while the smoky glass appears monolithic and opaque from certain vantage points and crystal clear from others like the surface of a pool. It is totally superficial one moment, then infinitely deep in another.

Now that you have conquered Venice, the next stop is Miami in December. What are you debuting?

We’re doing a large façade project in the Miami Design District. All we can say is that it’s very Miami and we’re neighbors with a very large John Baldessari piece. We also have a couple of other projects that will be completed this fall—a space for the new Curatorial Practice at the School of Visual Arts designed in collaboration with Charles Renfro, and a department store in Saint Petersburg, Russia.

Karen Wong is the deputy director of the New Museum and cofounder of NEW INC. Photography by David Sundberg.