- By

- Alexander Slotnick

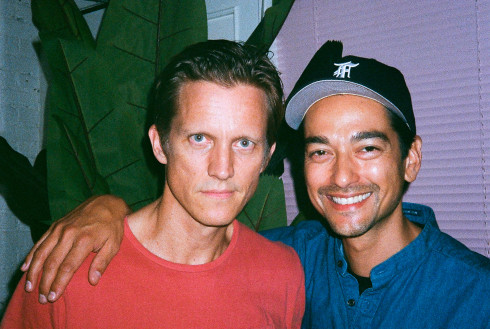

- Photography by

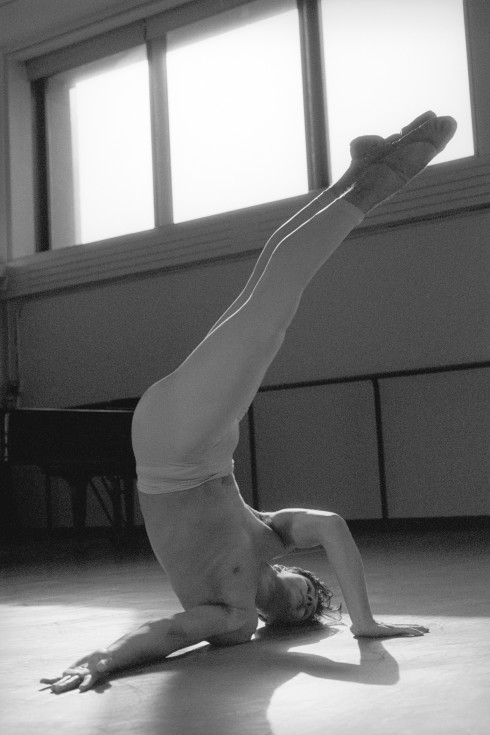

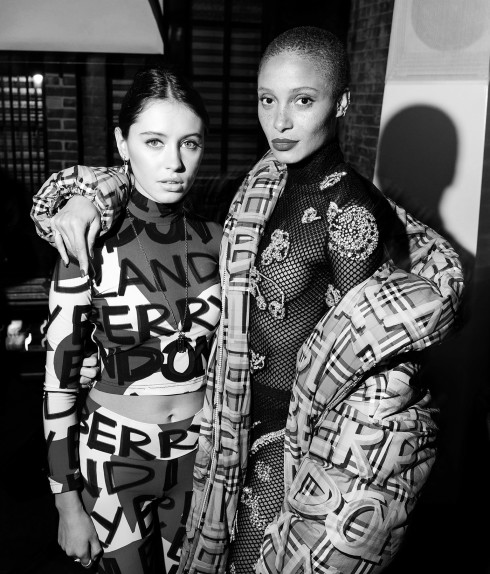

- Kurt Iswarienko

NIC PIZZOLATTO

Matthew McConaughey and Woody Harrelson come to HBO this Sunday with the première of True Detective, a new mystery series from writer and creator Nic Pizzolatto. In an interview from our ninth issue, Pizzolatto opens up about the haunting impact of his upbringing in the deep South and the role it continues to play in his work.

The South has stuck with writer Nic Pizzolatto. In climate, of course, it’s a sultry place—one that sticks quite literally—but for Pizzolatto, it’s also a region of emotional pull and possession. Of his formative years in the South, he says, “They are my most intense memories. They metaphysically haunt me.” And next year, when HBO airs True Detective—a new series created and written by Pizzolatto, directed by Cary Fukunaga, and starring the gallant duo of Woody Harrelson and Matthew McConaughey as detectives on a seventeen-year quest for a serial killer in deep Louisiana—the South will haunt viewers all over the world.

In conversation, Pizzolatto’s speech is measured and restrained, his wisdom well-considered. He talks with refreshing sobriety about his craft, exuding respect for his art and its tragic difficulty. Though Pizzolatto’s own stories often inhabit the southern United States, his taste in literature is global and cosmopolitan. Discussing personal favorites, he names Dostoevsky in the same breath as García Márquez, and lists Roberto Bolaño in sequence with the crime writer George V. Higgins. Last year, he delighted in Bubbles, by the German intellectual Peter Sloterdijk, while he considers Denis Johnson “probably the most important American writer of our time.”

Pizzolatto speaks with even more familiarity and expertise on the specifically Southern literary tradition he comes from: “There’s a kind of vaguely papal idea of some canon of ‘Southern Writers’—as if the South were a single place without the nuance and mutability of its separate components, but within that canon there’s a lot of Sacred American Treasures I consider pretty mediocre, though I’ll never ever be more specific than that,” he says. “The Mexican writer Juan Rulfo was closer to my idea of the South.”

That idea of the South comes straight from Pizzolatto’s childhood. He recalls, for instance, nights spent near a sluice at the end of his street, where he could behold the refinery of Sulphur from afar. The plant’s burning bulbs spiked the sky across a belt of the Louisiana Corridor knotted with dark. “They were so lit-up,” he says, “it was easy to see them as being New York City or Chicago—albeit with the odd flaming turret.” But when he thinks back on that view, it’s not in order to cherish the mirage of urbanism, but to illustrate the context of that mirage: the Louisiana water, Lake Charles, the pregnant austral night, the roaring and fecund Southern swath.

In the years since, Pizzolatto’s métier has taken him far from the South. He even lived for a few years in the bona fide Windy City itself, where he taught literature and writing at the University of Chicago and DePauw. His professorial track also led him to the University of North Carolina—veritably southern—though he shoved off from academia in 2010, when he realized he’d “never intended to pursue that career, really.” More importantly, he had solidified into a writer whose short stories and début novel Galveston garnered much-deserved esteem. Among a slew of awards, in 2006 he was named one of Poets and Writers magazine’s best new writers; in 2010 Galveston earned him the Prix du Premier Roman Étranger, the French Academy’s award for Best First Novel, Foreign.

Like so many people, he’s now colonized Los Angeles—his home for the past few years—for the sake of cinema; like so few, his art has already acquired the sterling sheen of success. The plan for True Detective had originally been to set the story unfolding in the shape of a fat novel. Now, Pizzolatto exalts in the pleasure of seeing his words crimp to the shapes of actors’ mouths, of working with director Cary Fukunaga, who directed Mia Wasikowska and Michael Fassbender in 2011’s Jane Eyre, and who will make True Detective a visual reality. For Pizzolatto, who had lived “the intensely monastic life of a novelist,” the collaboration intoxicates.

But his solitary, bookish life has been far from narrow. Pizzolatto’s career has brushed against everything from academic literature—which he rejects for its elitism—to pulp, which he strives to reinvent. His aesthetic goal is a kind of populist literature, which he manifested with great success in Galveston. Comprised of Southern noir plus healthy dashes of interstate travel and jejune prostitution, the novel might seem to be pure genre on first blush, but Pizzolatto has no qualms with such categorization: “I embrace genres that were formative for me as a reader to explore deeper philosophical issues.”

For example, in Galveston the basic sets are typical (a New Orleans dive bar, a motel housing a rainbow assortment of abuses, a truck’s cab after a night of finely rendered bloodbaths), though the spectrum of the characters’ pain and revelations is enlivening and rare. Pizzolatto has a talent for tuning into the language of popular stories, and then elevating them into fixtures of accessible fine art. For this reason, it seems television was always his destiny. “Television,” he says, “is the writer’s medium.” Enter True Detective. Enter crime, murder, intrigue. Still, Pizzolatto can speak at length on “individual memory and death memory,” “the governing media of our time,” “the pyramid scheme of modern academia.” His noir will disarm you, then sweep you off your feet. And it will always bring you home—to Pizzolatto’s home, at least, the South.

Any story connected to a specific place offers a plethora of potential approaches. Does the locale offer hard civil truths, à la The Wire? Or does it serve as a habitat for new breeds of vicious villains and desolate vistas, as in Breaking Bad? Pizzolatto waves such suggestions aside; he has no such agenda. For him, the art of telling stories is a personal affair—the South is simply the place he knows best, where he knows life and death most intimately. “My main subjects are probably memory, sex, and death—my big three. Your love and hate and memory and pain and joy are all one thing: a dream you had in an attempt to transcend death.”

Likewise, Pizzolatto does note a sinister, festering quality to those lands where he first lived. The southern states feature a denseness of grime and underbrush, of half-industrial wastelands, of desolate shorelines. True Detective is a story of murder, after all. Decay, Pizzolatto says, is a natural flavor in the southern air. “The South has visible but unremarked-upon corruption,” he explains. “Layers of overgrowth. Wilderness. Dark wilderness, channeled by the culture.” But then again, that culture was home. “I miss the food,” he remarks of Louisiana. He says it without hesitation, sighs a little, and though he now breathes California air, it’s clear the South has stuck with him.

True Detective premieres this Sunday on HBO.

Originally published in the Fall 2012 issue of The Last Magazine.

- By

- Alexander Slotnick

- Photography by

- Kurt Iswarienko