Jenna Gribbon, ‘Chrissy Taking Reference Photos for Her Paintings,’ 2017

- By

- Kevin Greenberg

All images courtesy of the artist.

JENNA GRIBBON'S PAINTINGS SUBVERT THE MALE GAZE

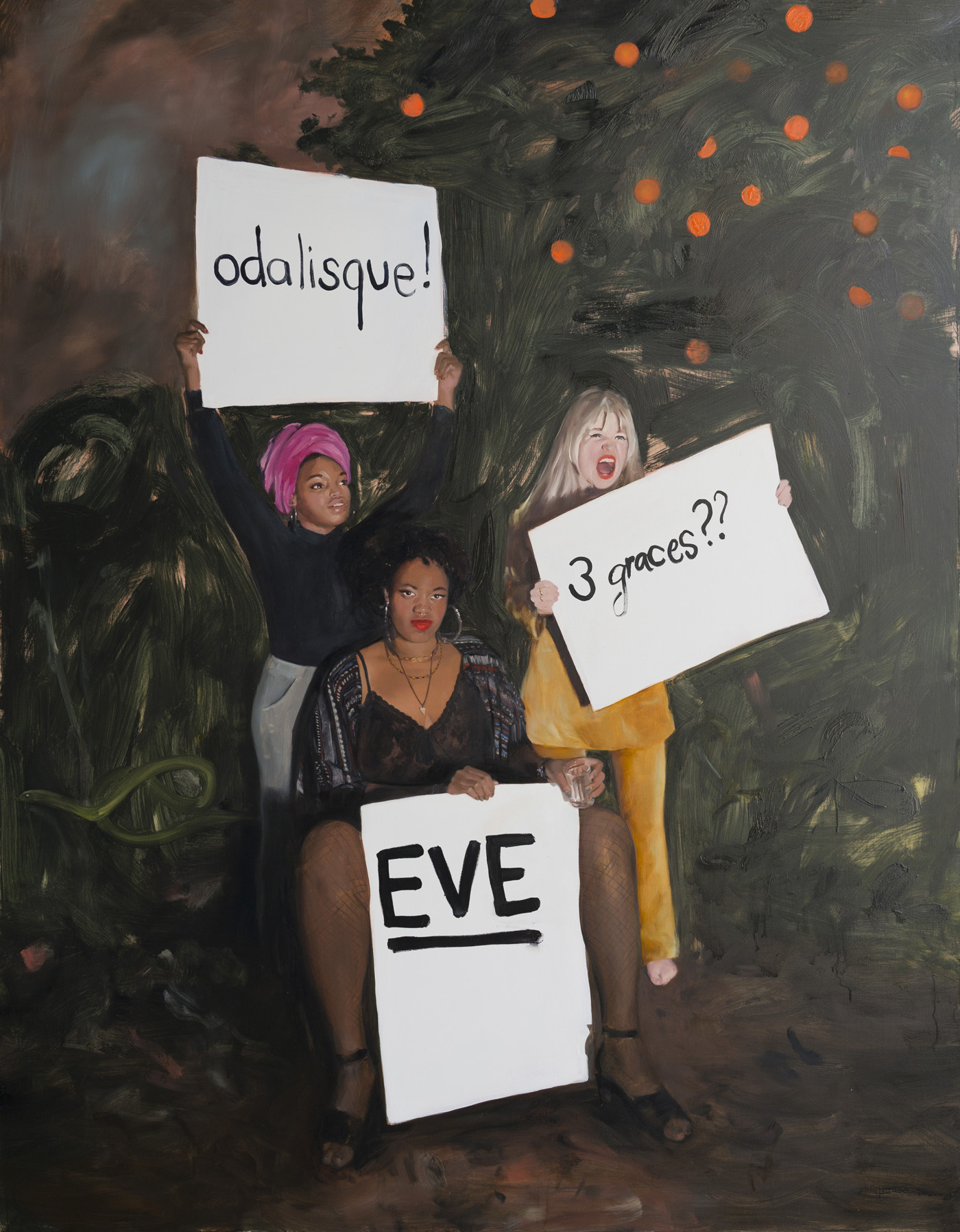

“People who are absorbed or actively engaged in an activity make the best subjects,” says the artist Jenna Gribbon. Upon first examination, Gribbon’s paintings have a beguiling quality familiar from centuries of romantically painted realism. In her canvases, attractive women, often nude or semi-nude, relax or engage in varied activities against a pastoral backdrop of sprawling fields, lush forests, and tranquil streams.

A closer look reveals a different, altogether more compelling narrative: Gribbon’s subjects are absorbed in self-actualizing activities, either alone, in pairs, or in groups. Often deep in conversation or erupting in laughter, they turn a blind eye to the viewer. Unselfconscious, con dent, they are the antithesis of the supine seductresses of the paintings of antiquity, whose mysterious smiles coyly acknowledge and even invite the male gaze. “Beauty can be a useful tool,” Gribbon says. “It can be subversive.”

“My paintings have a certain familiar appeal,” she adds, “pretty colors, beautiful women in what might appear to be seductive scenarios. But they’re also Trojan horses in a way; you’re drawn in and you expect to be able to interact with the subjects of the painting in the familiar modern or pre-modern way, but then when you actually begin to see what’s depicted, you have to address issues of agency, consent, and the relationship between the artist and viewer.”

“Overtly lush passages of oil paint, sugary colors, and rosy cheeks are a form of entrapment,” Gribbon has written. “Time spent in the painting leaves the viewer wondering if they, along with the artist, have been implicated. What are these women saying to us, and is it okay to feel pleasure in their presence? I believe the answer is yes, but it should be a mutual, shared, and liberated pleasure. We may not be able to, in the words of Audre Lorde, ‘dismantle the master’s house’ using the ‘master’s tools,’ but we might be able to walk around in the house, turn on the lights, and point out the cobwebs.”

What type of activity most draws Gribbon to a subject? “Preferably something interpersonal, like conversation,” she says. Indeed, conversation seems to be the life force that animates many of Gribbon’s paintings, and a number of her works explicitly depict subjects in the act of interlocution, either with eyes fixed on the painter/viewer or focused on an unseen subject beyond the painting’s frame.

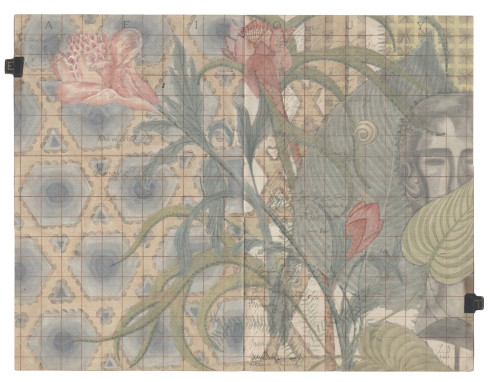

Gribbon’s works are also stylistically disorienting: Some elements, especially faces and hands, are rendered with the focused attention and realism of an old master or a skilled impressionist, while other aspects fall out of focus and lapse into something closer to abstraction. “I find that when I’m painting people, as long as the face is realistically rendered, most viewers will perceive the painting as realistic,” Gribbon notes.

But the tension between the diverse styles that Gribbon engages in a single canvas is one of her work’s most unique qualities. “I thought, ‘Why can’t I paint however I want?’” she says. “‘And why can’t I balance multiple styles in a single canvas?’

“A lot of my painting is about painting,” she continues. “I play a game with myself in which I channel other painters—how might they have seen this composition or chosen to paint it?”

Gribbon confesses that one of the major challenges of her work—and a central fascination—is unifying the jarring stylistic juxtapositions she often employs, “playing with making things feel ‘right’ or ‘wrong’ and grappling with the patrilineage of the painters I’m referencing.”

Her decision to avoid employing a consistently unified style is, perhaps ironically, one of the hallmarks of her work, contributing to its instantly recognizable character. For Gribbon, the variation she brings to a single canvas is a way of putting a uniquely female spin on her work. The stylistic ambiguity stands in marked contrast to the ego-fueled work of her almost exclusively white male forebears. “I feel like a recognizable mark is a very masculine idea,” she says.

Looking closely at Gribbon’s work, it’s easy to identify a rich firmament of influences: Her earlier paintings feature lush backdrops that recall the swirling, ominous perspective of Guercino’s Et in Arcadia Ego. Other influences include Manet, Whistler, John Singer Sargent, and Jan van Eyck. She remarks on the near-complete absence of female perspectives in the canon of painting prior to the twentieth century.

Part of the appeal of Gribbon’s work is her ability to create compelling compositions that subvert and operate on their own terms. This might be one reason why she is in high demand as a portrait artist. In fact, she was commissioned by Sofia Coppola to paint all of the period-appropriate portraits of Kirsten Dunst as Marie Antoinette for the 2006 biopic she directed. Looking at those paintings, which believably channel the style of the mid-eighteenth century, another important element of Gribbon’s work, humor, takes center stage.

Gribbon admits that the notion of ‘camp,’ which Susan Sontag famously described as involving “a new, more complex relation to ‘the serious,’” plays a central role in her work. According to Sontag, “One can be serious about the frivolous, frivolous about the serious,” and camp can in fact be used to “dethrone the serious.”

“There is an apparent lightness that may conceal an imbedded criticality,” Gribbon has written of her work, “making it easier to approach, or to use a campier reference, a spoonful of sugar for the proverbial medicine.

“[In 1922] Francis Picabia wrote, ‘If you want to have clean ideas, change them like shirts,’” she continued. “Absurdity and camp were two shirts he wore very well. Like Picabia, not much of my work is really intended to be humorous, but when it is intended it seems camp and absurdity are my preferred devices.”

Campy or not, Gribbon is a serious technician. Does her technique adhere to the methods of the past? What about preparatory drawings and studies, which often illuminate the rudiments of the artist’s intent?

Surprisingly, she concedes that drawing plays a minimal role in her practice. “I’ve always been impatient to get to the painting part,” she laughs.

- By

- Kevin Greenberg

All images courtesy of the artist.