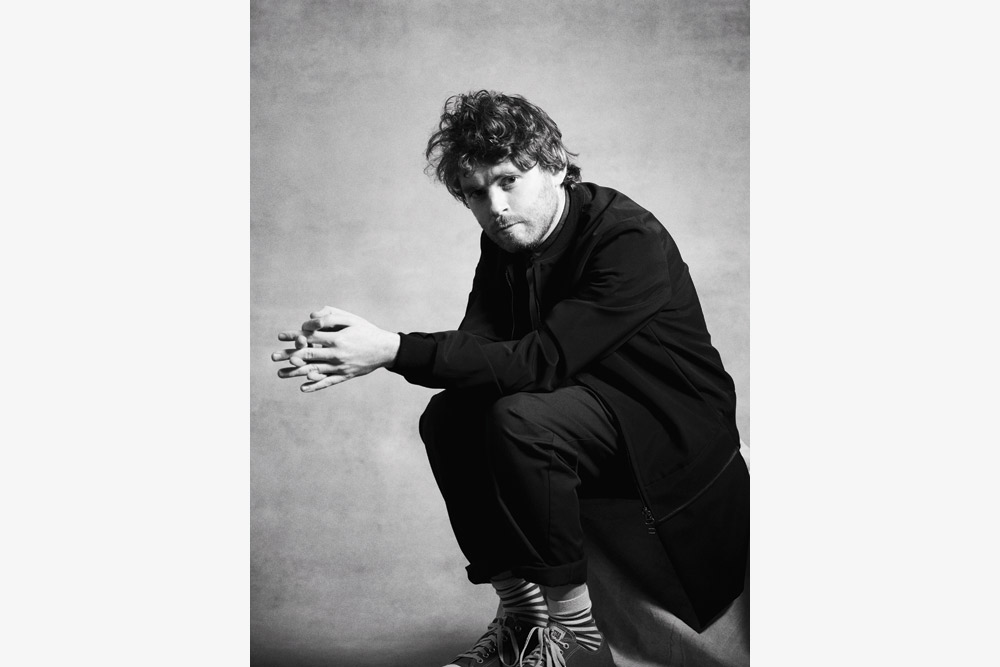

TLM10: GABRIEL KAHANE

Don’t try calling Gabriel Kahane a prodigy. That’s exactly what Andrew Solomon did in his encyclopedic nonfiction book Far from the Tree last year, featuring Kahane in a chapter overflowing with stories of child geniuses and other early-onset talents like fellow composer Nico Muhly, violinist Joshua Bell, and pianist Lang Lang, but Kahane is not having any of it. “I don’t actually know what his angle is,” he jokes of Solomon. “I was not a prodigy, I don’t think.”

But if Kahane was no boy wonder, he has become, at thirty-one, a composer and songwriter whose works are notable not only for their intricacy and nuance but also for their variety. In the past few years, Kahane has written orchestral works, chamber pieces, song cycles— notably Craigslistlieder, with text gleaned from, yes, that benighted Internet catch-all—two albums’ worth of folksy, guitar-driven “pop songs,” and a musical for the Public Theater in New York. So eclectic are his compositions, in fact, that when he mentions an upcoming tour through the Midwest, it’s unclear at first exactly what sort of music he’ll be playing.

Kahane grew up in upstate New York and then the Bay Area, the son of highly-acclaimed classical pianist and conductor Jeffrey Kahane, who Gabriel says was very hands-off in terms of his musical education. “I think he wanted me to find music on my own if I was going to do it,” he says. “He was always afraid of asserting too much pressure in any direction. Actually, when I transferred from the New England Conservatory to Brown as a sophomore, he expressed relief that I had left conservatory because he just felt like it was not the right atmosphere for me to flower as a person or a thinker or a musician.” Kahane credits his father with instilling him with the understanding that being a musician requires more than just perfect pitch and a knowledge of harmonic intervals, an attitude that he continues to adhere to. “He’s just always done whatever he’s most wanted to do creatively,” he says of the elder Kahane. “I think his biggest impact on me has been to provide a model of real artistic integrity and this idea that being a student of the world and a student of life in general makes a better artist than just sitting in a practice room for hours a day.”

To that end, Kahane points to his time at Brown rather than his year at conservatory as having had a larger influence on the path of his work today. “I was definitely exposed to a lot of things outside of music that had a really big impact on how I think about music, like poststructuralist theory, and the idea that how you frame a text is as important as what the text is,” he explains. Derrida himself would surely have appreciated the appeal of Craigslistlieder, one of Kahane’s earliest major works and perhaps the one he is still best known for today. “I think for me, doing a piece like Craigslistlieder in bars was an experiment in what happens when you put dense, somewhat dissonant art music in a club and don’t put a gilded frame around it,” he says. “The answer was that people thought it was cool and they laughed and they were drinking beer and it wasn’t precious, and then a few years later Audra McDonald can sing it at Carnegie Hall and people have a slightly different reaction.”

Kahane’s understanding of framing and the wider context of performance can also in some ways be seen as the reason he left conservatory in the first place. After matriculating to study jazz piano, Kahane says he quickly realized that the “hermetically sealed” world of improvised music was not for him: “I found very early on that jazz was this super-insular community where it was jazz musicians playing for other jazz musicians, and also it seemed largely a community that was not engaged with the world,” he says. “I remember being at the Village Vanguard on break from college, hearing some jazz pianist make a reference to some jazz standard, and having this gaggle of undergraduate jazz piano majors giggling, and thinking, This is not who I want to make music for. And also I just wasn’t good enough at it.”

Not being good enough ended up being for the best for Kahane, who eventually found his way back to the piano before letting his classical studies slide again in his early twenties as he shifted his energies to composition rather than performance, trying to find his way in his new hometown of New York. The spur for Craigslistlieder in 2006, in fact, seems to have been the simple urge to just make something happen. “I sent out an email to my mailing list, which at that point was like seventeen people, and said, On such and such date I’m playing a show here and I’m going to premiere Craigslistlieder,” he recalls. “I hadn’t written it yet, so I sort of forced myself to write part of it.”

Kahane spent the next handful of years working on a number of chamber works and shorter piano pieces, including one which his father commissioned for a performance at Lincoln Center in 2009 about his dog Django. He released a self-titled album of folk songs, which he performed himself, in 2008, and another called Where Are the Arms in 2011. Then, last spring, his musical February House—about the Brooklyn Heights home WH Auden, Benjamin Britten, Carson McCullers, and Gypsy Rose Lee shared as newly-minted adults in the early Forties—premiered at the Public Theater, the start of what Kahane hopes will be a continuing collaboration with the company. The show served as a homecoming of sorts for him, having spent much of his time in high school and college acting in student productions. “To return to the theater, and to return as a composer, has been a wonderful thing for me,” he says.

With the six years it took to bring February House to the stage now behind him, Kahane is currently at work on another song cycle, this one based on the WPA’s American Guide Series, which put then-rising talents like John Steinbeck, Saul Bellow, Zora Neale Hurston, Ralph Ellison, and Richard Wright to work recording the history, geography, and culture of each of the contiguous forty-eight states. “It felt very timely, given the major questions that our country’s going through about what the role of government ought to be or ought not to be,” he explains, “and I started thinking like, Well, how do I do a piece about the WPA that doesn’t come off as propaganda?” The work will serve as the capstone to Kahane’s two seasons as composer-in-residence at Orpheus Chamber Orchestra, and premiered in April at Dartmouth before landing at Carnegie Hall at the end of the month.

The libretto, composed of found text—much like Craigslistlieder—is, Kahane says, his “version of making creation through curation, of collage art, in a certain way.” The words are by turns lyrical and blunt, poetic and candid, reflecting the variety of writer’s voices across America. “The subtext of the piece, I hope, is going to be that the fact that this exists is amazing and—whatever we think the role of government should be—the fact that the country came together and made this document of itself is just really beautiful,” he says. “I guess it’s sort of a lens through which I’m reckoning with being an American and trying to reclaim patriotism for the left.”

Kahane says that, given his “self-diagnosed ADD,” he can’t imagine a future that doesn’t involve a mix of classical music, theater, and folk songs. “Writing musical theater lyrics and writing lyrics for my pop songs is a completely different muscle being exercised,” he says, “as is just writing music for that matter.” The different genres help inform each other, offering alternatives and competing models for Kahane to express himself. Still, he acknowledges the varied demands of the divergent forms and says that working across all of them has helped him recognize the inherent limitations of each. “With theater lyrics, you need the audience to hear the lyric clearly the first time, whereas when you’re writing lyrics for a pop song, you can be more opaque or oblique because generally you’re intending it as a recorded medium where you want the person to spend fifty listens getting to know the lyric and making sense of it,” he explains. “I think that’s maybe what led a lot of indie-rock lyricists to be so oblique to the point where you have no idea what the fuck they’re saying. Personally I want to hold myself to a standard of being incredibly specific with pop-song lyrics, even if they’re not immediately apparent as being about something.”

While this sort of genre-crossing may seem to be a recent, uniquely postmodern development, Kahane insists that he sees himself as part of a long American tradition of boundary-jumping that goes back generations. “Schoenberg loved Gershwin’s songs and was super-jealous of how easy it was for Gershwin to write a perfect melody,” he notes. “For all of the atonality and insanity of Schoenberg’s music, he was totally jealous of Gershwin’s gift for simplicity, and vice versa.” Kahane himself seems to be aiming for the perfect middle ground between Pierrot Lunaire and Porgy and Bess. “I think exposure to some of those literary theory ideas in college set me on the path to think, Well what if I make popular music that’s actually more sophisticated, but I pretend that it’s pop music and don’t tell them?” he says. “I want to write music that seems simpler than it is, as opposed to being ostentatiously complex.”

Still, if you ask Kahane, he’ll try to convince you that his eclectic genius is little more than the result of his own constraints. “I think, in a weird way, having grown up without a great deal of pressure, say, to become a concert pianist, the limitations that I had when I became really interested in music ultimately determined the direction that I went in. Which is to say, if I had had concert technique by the time I was eighteen, I might have ended up a boring classical pianist or whatever. I think that I’m doing the only things that I can do, and coming up with a way of distinguishing myself from the world by finding what’s different about me. I think that my limitations have actually helped me to figure out what is more personal in what I do.”

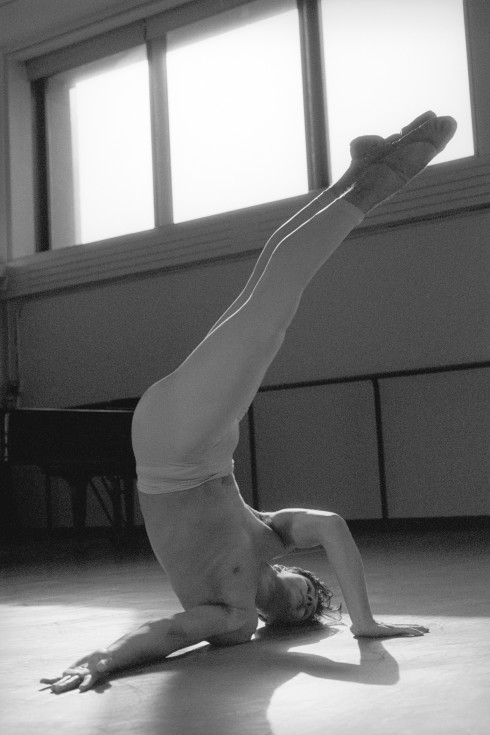

For more information, please visit GabrielKahane.com. Styling by Zara Zachrisson. Photographer’s assistants: Christopher Davis, Stas May, and Katie Bell Moore. Set design by Whitney Hellesen. Digital technician: Clare Chong.