IRENE KOPELMAN

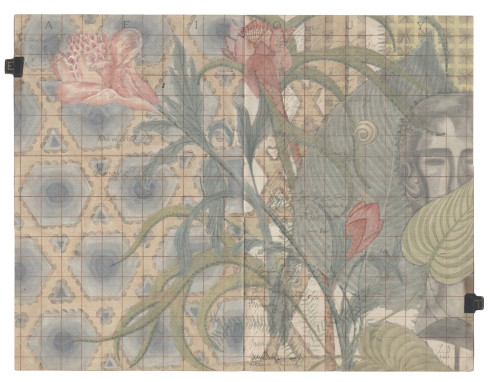

For the artist Irene Kopelman, exposure is everything. Whether it’s the seared expanses of Egypt’s White Desert or the freezing waters of the Antarctic, “If I’m not there, out in the elements and directly observing things, even if it’s windy or bitterly cold, the pieces won’t develop the way they should,” she says.

Kopelman’s work marries the clinical distance of scientific observation with an almost spiritual reverence for landscape and the objects, large and small, that comprise it. Wonder in the face of nature’s indifference to human striving is nothing new, of course. Bergsonian notions of the sublime consumed the psyche of pre-modern Europe and colored much of the continent’s art and literature for decades. But much like the phenomenology of Edmund Husserl and Martin Heidegger, Kopelman’s work employs the otherness of nature to reveal something integral about the recesses of the individual self.

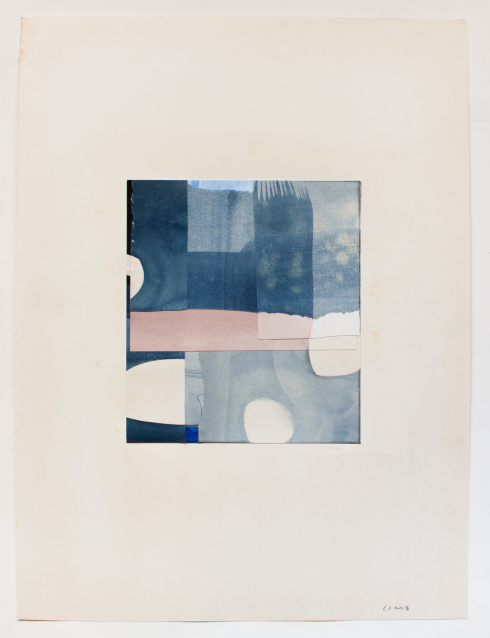

For centuries, the dualism of Western thought treated nature as an antagonist—a dangerous, unpredictable enemy to be tamed, reshaped, and exploited by humankind. Kopelman’s work, on the other hand, reflects an Eastern approach of integration and the unraveling of the ego in favor of acceptance of one’s own very finite place in the natural order. At first, her elegant, small-scale, meticulously catalogued graphite drawings suggest a scientist’s precision (and accompanying objectivity), but the thought that informs the action betrays a poetic, introspective impulse. For 2009’s Meditation Piece (based on Allan Kaprow’s 1981 series of the same name), Kopelman selected a single stone from the limitless expanse of the White Desert and drew it from the same angle every day for a month. The variety of the resulting drawings reflects the fragility and subjectivity of consciousness and perception.

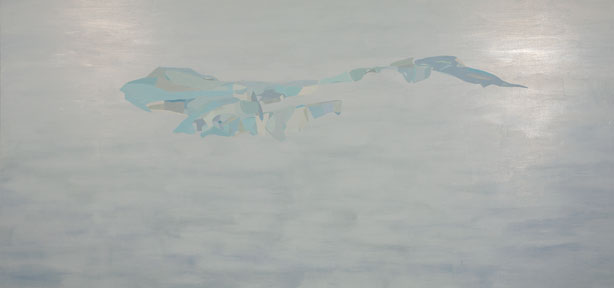

Kopelman’s large paintings of the Antarctic, inspired by a drawing expedition she took in January 2010 aboard a sailing research vessel built for eight people, recall the grand tradition of 19th-century Romantic landscapes. But their abstracted, almost pixelated execution suggests a contemporary approach, as well as the restricted conditions that Kopelman experienced during her trip and the vantage point they afforded her on her subject.

“Weather and space constrictions were an intrinsic part of the project,” Kopelman explains. “Cold, snow, rain, the boat drifting, the boat changing locations, the impossibility of going on shore alone and at will, and so on all became part of the process of the project.”

Of course, Kopelman’s pieces also underscore the beauty of the landscapes she documents. Like the work of photographer Juergen Bergbauer, whose obsessive catalogs of honed rocks (and the stark, disembodied compositions he creates from them) highlight his subjects’ simple beauty while simultaneously expressing the futility of documenting their subtle differences, Kopelman’s drawings, paintings, and sculptures betray her deep love of the morphology of the world around her.

So where to next? Kopelman is currently in Central Europe, experimenting with ceramics. A quirk in her process, she says, is to select locations based on her current interests in color, texture, and material. “I guess I find a texture I like and then plan a trip to a place where I hope to find it,” she laughs, noting that she thinks the volcanic reaches of Eastern Ethiopia might prove to be a nice geographical match for the pocked and craggy slabs she’s lately been retrieving each day from the kilns.

Ultimately, it’s elemental.

All images courtesy of the artist and LABOR.