TLM09: ANDY COOLQUITT

“It might be instructive to think about forms of theater as used in retail design,” Andy Coolquitt says. “A Comme des Garçons store? Bogus theater. It’s a lot like a gallery. An Urban Outfitters store, despite having a lot more stock out on the floor, is still a semi-curated space. A Salvation Army, on the other hand, with its raw accumulation of all kinds of different, discarded objects, that’s pure volume, pure theater. I’m shooting for something between the Urban Outfitters and the Salvation Army.”

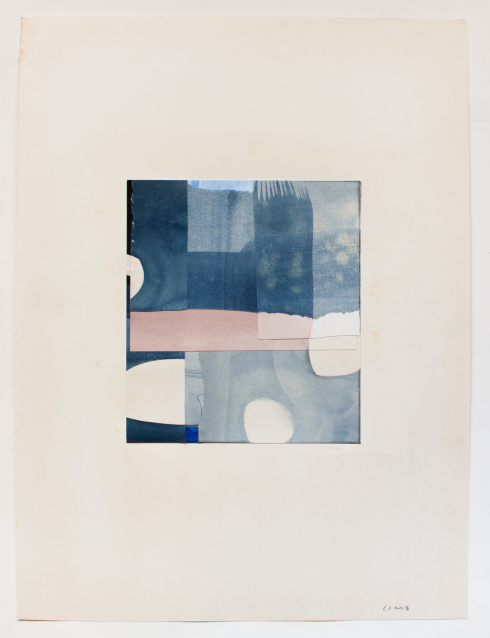

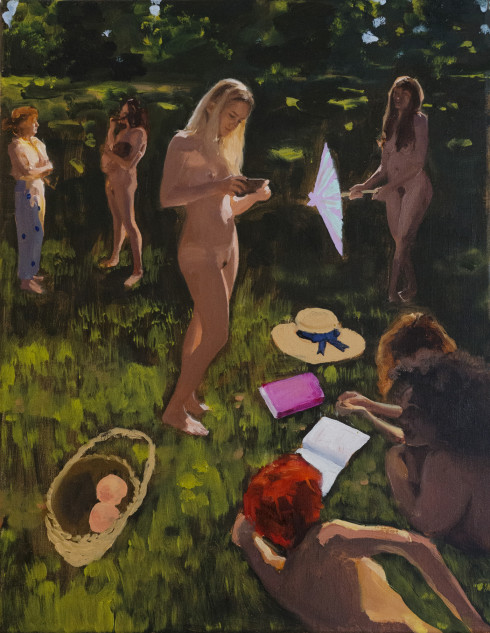

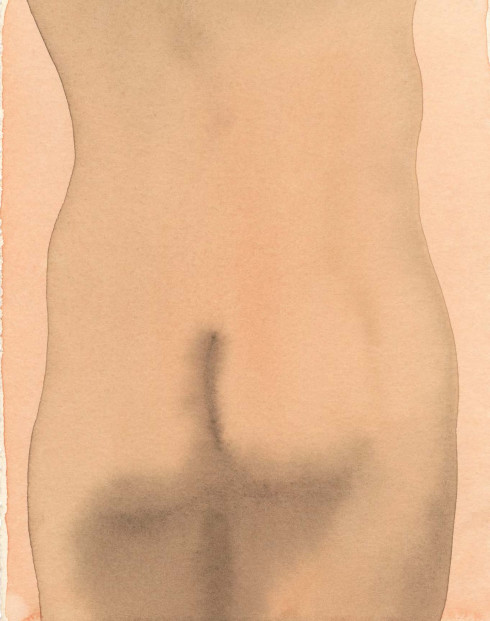

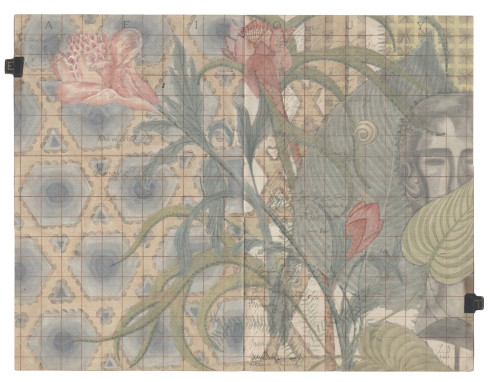

Coolquitt’s work is about relationships, about negotiating space and culture through objects, both reclaimed and roughly cobbled-together. For almost twenty-five years, he has built an art practice that blends conceptual art and sculpture with ideas more commonly associated with design, performance, and experimental psychology. Coolquitt lives and works in Austin, Texas, where since 1994 he has created site-specific pieces particular to his house and studio, and hosted diverse events that animate them. Coolquitt’s first solo show in New York, at Lisa Cooley’s Orchard Street gallery in 2008, was a revelation for many who saw it, and helped raise him out of obscurity. Since then, he’s shown widely, both domestically and abroad, and Houston’s Blaffer Art Museum will host a mid-career survey of his work during the summer of 2013.

Although he creates a broad array of stand-alone objects (both functional and decidedly dysfunctional), Coolquitt’s most ambitious works typically take the form of unique “environments” in which diverse objects, pieced together by hand into assemblages or left as-is and placed casually together like a group of strangers in a waiting room, create subtle modifications in the way the visitor perceives the art object and navigates the gallery environment.

After studying at the University of Texas at Austin in the late 1980s, Coolquitt migrated to UCLA to study with Charles Ray and Paul McCarthy, both of whom were actively exploring notions of performance and social relationships in their work. Coolquitt was especially fascinated by the work of Allan Kaprow, McCarthy’s mentor, who championed an art of engagement that would prefigure the “relational aesthetics” later popularized by the theorist and art historian Nicolas Bourriaud. Coolquitt would later become interested in the work of the Viennese artist Franz West, who encouraged people to actively engage with the plaster-coated objects he termed “adaptives”—the ultimate art-viewing transgression. Coolquitt’s pieces also call to mind the work of Franz Erhard Walther, whose often-simple sculptures, built from utilitarian materials, are “activated” by one or more people, forcing them into a new relationship with each other and their environment.

“I think a lot about density,” Coolquitt says. He spent his youth navigating the sparsely developed flats of Texas, and considers the close quarters of a city like New York to be “oppressive.” “Of course, after living in New York for several years, I began to view the proximity to so many people and objects as sophisticated,” he says, “and found I had come to think of the vastness of Texas as representing emptiness and death.” Negotiating the complex terrain of one of Coolquitt’s environments, which are not so much cluttered as “thickly settled” (to use a decidedly non-Texan term), it’s hard not to think about this shift in his thinking. Displayed in a gallery setting, Coolquitt’s pieces challenge the conventional ways we view art and appraise its value as a commodity, as well as the ways we form and maintain relationships with other people and society at large. The artist’s long, linear lamps—assembled from metal pipes of various colors—often span from floor to wall, amidst assemblages of various scavenged items, usually flotsam from poor, urban areas. “I take a generally dim view of contemporary society, but I’m interested in comfort,” Coolquitt says, although it quickly becomes clear to even the most casual visitor that Coolquitt is less concerned with producing relaxing settings than in engineering spaces that raise questions about how we arrive at a comfortable position—in an environment, with others, with oneself—or often fail to do so.

Nevertheless, there’s great visual and mental pleasure to be had from immersing oneself in Coolquitt’s work. However pessimistic his outlook might be regarding the direction of things writ large, Coolquitt’s belief in art as a positive force is undiminished. “I think of art as a prosthetic,” he says, one which allows people to interact, and which has the capacity to be therapeutic. In the presence of Coolquitt’s environments and the individual objects of which they are composed, it’s hard not to feel a little more alert, engaged, and maybe even more alive.

“Andy Coolquitt” will run from May 25 to August 24 at the Blaffer Art Museum, Houston. Images courtesy of the artist and Lisa Cooley, New York.