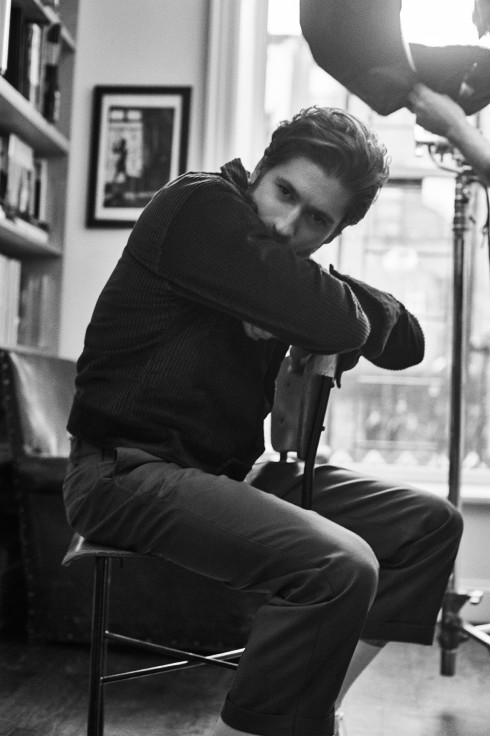

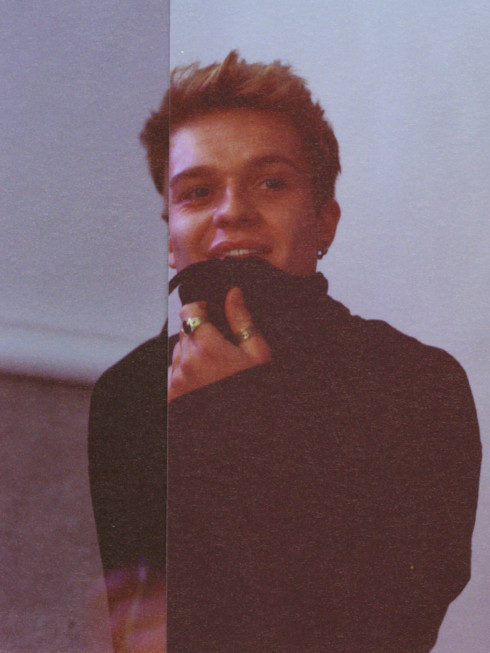

Jacket by Jil Sander. Earrings, worn throughout, by Sophie Buhai.

- By

- Jonathan Shia

- Photography by

- Whitney Hayes

- Styling by

- Shayna Arnold

Hair by Tsuyoshi Harada. Makeup by Maki H at The Wall Group. Photographer’s assistants: Jordan Geiger and Vadim Krizhanovsky. Shot at Slate Studios, New York.

Celia Keenan-Bolger Dissects the State of the Nation

When Celia Keenan-Bolger was a young girl growing up outside Detroit, she was asked to present a monologue as her audition for a play. Already a veteran of musicals, she was used to singing on command, but this request caused some confusion in her family. “My parents were like, ‘What’s a monologue?’” she laughs, “and I was like, ‘Oh, it would just be me talking for a long time.’” Unable to find a suitable work for her age, her mother suggested she perform part of To Kill a Mockingbird, Harper Lee’s iconic novel written in the voice of the six-year-old Scout Finch, whose father Atticus tries heroically to defend an obviously innocent black man against charges of raping a white women in racist Alabama. “It was a really important book in my household,” Keenan-Bolger recalls. “It was one of the first long books that I remember my mom reading to me.” She chose an intensely dramatic moment, in which Scout manages to disarm a lynch mob intent on attacking her father and the man he is defending with her innocence.

Years later, Keenan-Bolger is revisiting that scene again eight times a week, this time on Broadway in Aaron Sorkin’s hit adaptation starring Jeff Daniels as Atticus. Now forty-one, she is no stranger to playing younger (two of her previous three Tony nominations were also for characters well below voting age), but bringing one of American literature’s most famous young girls to life has been a unique experience. “It came very naturally,” she says about her tender-yet-fierce performance as Scout. “I can’t tell if that’s because every little girl who reads that book wants to be Scout Finch or if there was something that specifically spoke to me about her—just the strength and curiosity and innocence of that character that really resonated with me when I was a kid—but revisiting it, I was like, ‘I have so much access to this person.’”

Back in the fall of 2017, after Sorkin had finished his first draft, Keenan-Bolger received a call from her agent asking if she would be willing to read the part of Scout in an initial workshop. The original plan had been for actual children to play the central roles of Scout, her brother Jem, and their friend Dill, but the creative team quickly made the decision to use adult actors instead (Will Pullen and Gideon Glick now portray the two teenage boys). Sorkin, the celebrated Oscar-winning writer behind The Social Network, The West Wing, Moneyball, and A Few Good Men, emphasized that he was writing a memory play—a term invented by Tennessee Williams to describe what is essentially an extended flashback—adding a layer of poignancy as Scout looks back on her own lost innocence. “One of the best parts of this process is watching somebody who is as good at his job as Aaron Sorkin is,” says Keenan-Bolger, who remained involved throughout the entire journey to Broadway, where the play opened late last year. “After that first reading, I was like, ‘So we’re basically ready to go,’ and I think he’s done something like forty subsequent drafts since then, just rewriting and rewriting and rewriting.”

All that fine-tuning has resulted in a play that remains surprisingly loyal to Lee’s original while updating it to fit our times and adding Sorkin’s characteristic sharp wit. The central plot, in which Tom Robinson is found guilty by an all-white jury for a crime he would have been physically unable to commit, “couldn’t be more relevant,” Keenan-Bolger says. “It also processes this question of where we have been as a country and where we’ve come from. It feels like when Harper Lee wrote it in 1960, she was trying to look back at a simpler time in 1934 and now here we are in 2019 looking back on the Sixties looking back on the Thirties. The play asks the audience to really turn over questions about who we are as a country, where we have been, and where we’re going.” The show also, in its unearthing of the latent racism and bigotry that runs to our nation’s core, reflects provocatively on our current state. “It does feel like there’s a big circle,” she adds. “Obviously I think if we had done the play when Barack Obama was the president, I would feel like we’ve come so far and somehow just two years later it feels like we’re right back where we started—which of course isn’t true, but it feels truer certainly than it ever has in my lifetime.”

In some ways, Keenan-Bolger’s latest project is a culmination of two essential threads for her. The daughter of a teacher and an urban planner, she is the eldest of three, all of whom have ended up actors. She performed in local children’s theaters around Detroit throughout her childhood before graduating from the University of Michigan’s famed musical theater program and has appeared in a number of notable Broadway productions since then, from The 25th Annual Putnam County Spelling Bee to Peter and the Starcatcher and a recent revival of The Glass Menagerie. To Kill a Mockingbird marks her fourth Tony nomination, but she says it is the most special to her as someone who is deeply driven by politics. “I’ve had a few moments in my adult life where I was like, ‘Am I going to just keep being an actor?’” she admits. “Actually in 2008 I moved to Pennsylvania and became a field organizer for Obama’s campaign because I was obsessed with the election and he was my candidate. If I was made to give this up, I probably would end up in some sort of social justice work. Those two parts of my life always felt so separate. I would go and work for Obama or I would get to do theater, but they would never connect. What’s been so moving about this play is that I do feel like it’s giving me this beautiful combination of these two really important forces in my life.”

Like much of the arts community, Keenan-Bolger is an outspoken critic of the Trump administration and she says she has been touched by the response the play—which pits the impossibly noble Atticus against a particularly American form of hatred—has been receiving. “Processing these questions about our country with fourteen hundred other people is incredibly moving,” she says. “There are not a lot of places to come together and have this back-and-forth with the audience and the actors to experience that transference of energy and ideas about our country.” She understands, she says, that art is not the solution to everything of course, but she hopes that works like this can have an impact in their own way. “Sonia Sotomayor came and saw the show and was like, ‘This play is so important,’” she explains. “I think sometimes it feels so self-serving to be an actor and when somebody of her intelligence comes and says something like that I’m like, ‘You know what? I’m going to really believe you.’ Throughout history, art has been an amazing tool to shape ideas and to change minds about the way we treat each other and how we want to be better people. I think it certainly can’t always be that way, but when it is, it is really, really important.”

To Kill a Mockingbird is now running at the Shubert Theatre, New York.

- By

- Jonathan Shia

- Photography by

- Whitney Hayes

- Styling by

- Shayna Arnold

Hair by Tsuyoshi Harada. Makeup by Maki H at The Wall Group. Photographer’s assistants: Jordan Geiger and Vadim Krizhanovsky. Shot at Slate Studios, New York.