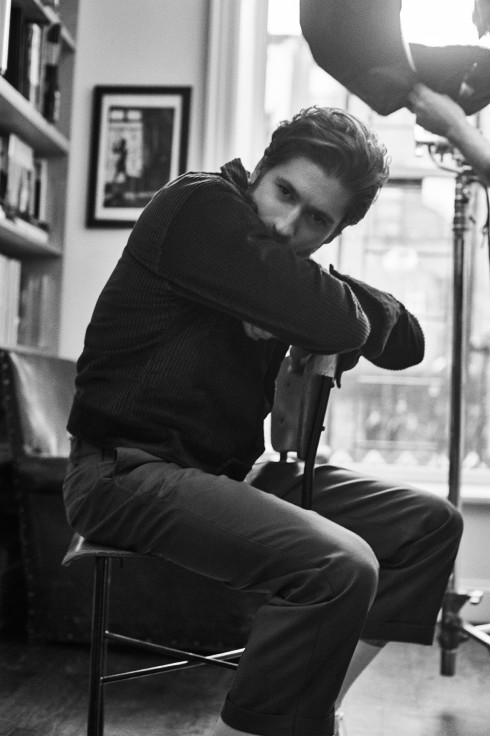

- By

- Jonathan Shia

- Photography by

- Matt Kaelin

ANNIE BAKER

If you ask Annie Baker about her success, she’ll try to pass it off as mere luck. The young playwright, whose Off-Broadway work Circle Mirror Transformation was heralded as the arrival of an invigorating new talent by the city’s critics in 2009, is irredeemably self-effacing. “At the time I actually felt like it was a really bad idea,” she says of the play, about the slowly evolving web of relationships between the four students of an ersatz drama class and their teacher. “It could be such a smarmy concept.”

But Circle Mirror Transformation proved to be much more than its clever premise. The characters perform a series of unintentionally hilarious and revealing acting exercises, drawn from the annals of drama therapy, but the result is emotional sincerity. “I was interested in the theatrics of theatrical exercises, like how actually gorgeous and theatrical a bunch of people lying on the ground counting is,” Baker says. “Those exercises are never actually performed for an audience, but I actually think they’re really good theater unto themselves.”

Baker, now twenty-nine, was first drawn to the stage as a teenager, a “typical theater-obsessed high school student.” She went on to study dramatic writing at New York University’s Tisch School of the Arts and playwriting at Brooklyn College. Then, to hear her tell it, she had her first production handed to her when an actress in a short play she had written passed along the script for Body Awareness, which shows what happens when a nude photographer presents his wares during Body Awareness Week at a small New England liberal arts school, to the artistic director at the Atlantic Theater Company. “The actress was like, ‘Give me any play you want, and I won’t even read it, I’ll give it to him,’” she recalls. “And he read it in bed at night or whatever, and wanted to perform it. So I got this phone call and that was my first production.”

The process of placing Circle Mirror Transformation on the stage at Playwrights Horizons was, per Baker, similarly painless. The playwright spent the summer of 2008 working on the play at the Sundance Institute Theatre Lab in Utah. “It was like a month in the mountains, and we all fucked around and played acting exercises,” she says. “I rewrote it a lot and in that summer, it became the play that it ended up becoming.” The literary manager of Playwrights Horizons saw her final presentation, and that was that. “I actually didn’t even know that you could make even half a living playwriting,” she laughs. “I wouldn’t say that it was a professional goal, or that there was a moment when it became a professional goal. I’d say I became a professional playwright before I even knew that it was possible to become a professional playwright.”

But while Baker is quick to point to fortune and chance as her guardian angels, her work demonstrates that she has an innate ability for crafting language into phrases that are both casual and nuanced. “One of the reasons I’m attracted to playwriting is how fragmented and grammatically lame it is,” she explains. “I’m interested in bad grammar and I’m interested in cliché and I’m interested in banalities.” You won’t find the soaring oratory of Tony Kushner’s AIDS patients and Tom Stoppard’s disillusioned intellectuals in her work; Baker’s characters speak softly, naturally, honestly.

Baker says that one of the hardest lessons for her to learn as she has worked on her craft over the years has been simply to get out of her own way and to come to terms with her own writing habits. “I used to give myself a lot of shit and feel like a loser,” she says, “because I knew people who got up at six in the morning and wrote till noon, and I can’t do that.” Similarly, it took her some time to realize that the “rules” of playwriting she learned in school are not hard and fast. “It’s OK if I have a sense of the ending; if I can sort of smell it, it’s OK, but I can’t know exactly what’s going to happen,” she explains. “And that was really hard for me to learn, because in college I had a lot of teachers who were like, ‘You have to know what’s going to happen.’”

Baker is also at work on a pilot for HBO about a business-school graduate who returns to the “pseudo-utopian, socialist farm in Northern California” of her youth. “It was my one idea for a TV show,” she says. “I still have no other ideas.” Writing for television has come as somewhat of a culture shock for Baker, with its tighter deadlines and increased structure, and especially its open-endedness. “A good pilot is different than a good play,” she says, “because a good pilot is all about hinting at what’s to come and trying to get people to tune in the next week, and a play is its own contained, beautiful thing.”

In the end, the driving force behind Baker’s work is an unyielding passion for the usage of the English language, both glorious and everyday. “I love beautiful sentences,” she says. The words she places in her characters’ mouths are direct and candid, bits and pieces of thoughts struggling to take shape, but the overall effect is a complete and unified whole. “I’ll never stop writing plays,” she says, “because it gives me more pleasure than anything else in the world.”

- By

- Jonathan Shia

- Photography by

- Matt Kaelin