- By

- Jonathan Shia

- Photography by

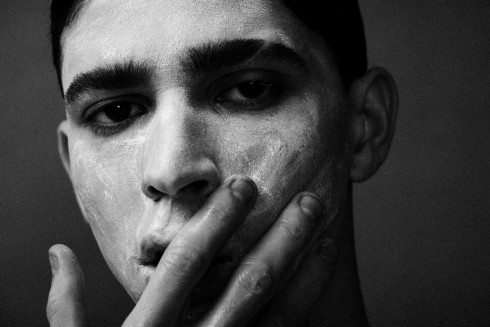

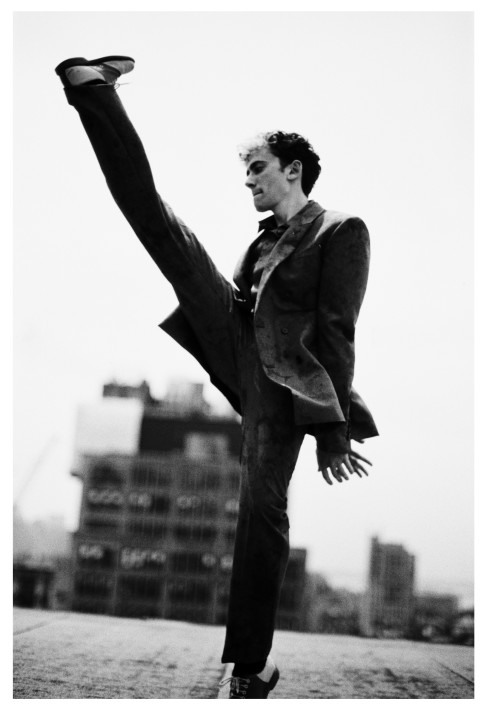

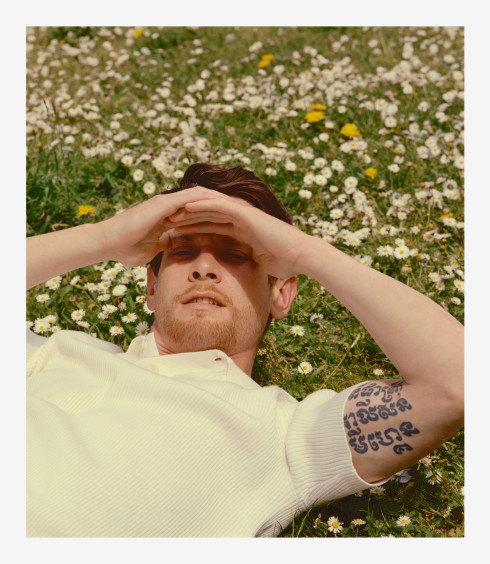

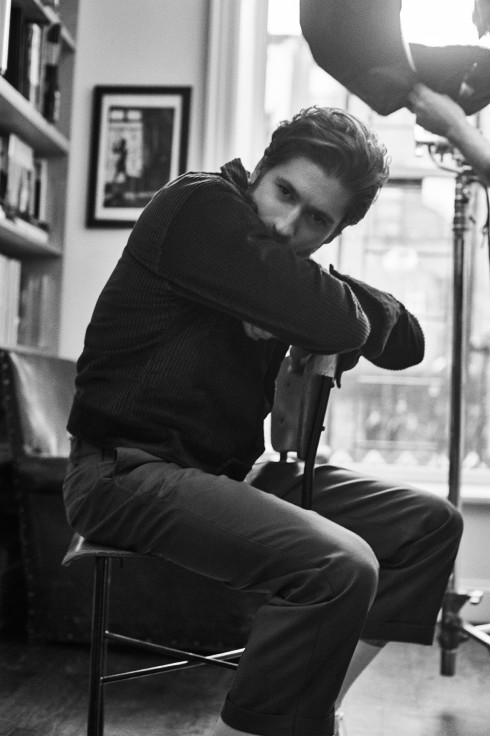

- Ben Lamberty

Hair by Yuhi Kim at Bridge Artists. Makeup by Misha Shahzada at See Management.

JIN HA

Before June 5, 1988, there had been zero Asian-American Tony winners, but that night’s ceremony produced two. The playwright David Henry Hwang took home the award for Best Play for M. Butterfly, about the relationship between a French civil servant posted to Beijing and the Peking opera singer-turned-spy he falls in love with, played by BD Wong, who also won for his performance. For the actor Jin Ha, who is now making his Broadway début in Wong’s role as Song Liling in the revival directed by Julie Taylor and starring Clive Owen, those two pioneers have served as inspirations for him his entire life. “Both of them have been lighthouses for me,” he says. “Growing up as an Asian-American consumer but also as an actor myself, I’ve looked up to them. To be able to have a chance to have a go at the role and to inhabit it is a dream.”

Based on a true story, M. Butterfly tracks the growing romance between Owen’s Rene Gallimard and Song, who impersonates a woman to win the Frenchman’s love and trust and, eventually, to steal diplomatic secrets from him for Chairman Mao. It was an understandably groundbreaking and revelatory play when it opened at the end of the Eighties, but with today’s more widespread knowledge of the nuances of identity, it takes on new subtlety and surprising twists. Hwang’s trenchant criticisms of Orientalism—the Puccini opera from which he takes his title being only one of the most flagrant examples of this trend in high art—continue to resonate just as clearly now, while the ambiguities about gender and sexuality—Gallimard is married to a woman—seem particularly relevant. “Even though it’s a ‘period’ piece, I as an artist today have to contextualize it in our current world,” Ha explains.

Given the contemporary discussion surrounding which artists have the right to tell which story, Ha, as a cisgender, straight man who beat out some gender-nonconforming actors for the part, says he was prepared for some backlash for playing Song, who, while it becomes clear by the second act does not suffer from gender dysphoria, nonetheless comfortably encourages the belief that he is a woman, but luckily the response has been largely positive. (He is also much more assured in his desires than Gallimard, who seems to suffer from his own internalized homophobia.) “I would absolutely understand why somebody would be upset by the casting,” he says. “I understand issues of representation in terms of casting because obviously, as an Asian-American, I see it happening today where whitewashing is rampant. I don’t regret taking this role and my hope is that my understanding and my work on and off stage prompts the necessary and nuanced conversations that need to be had about what is masculinity.”

That idea of representation is vital to understanding the import of M. Butterfly, even in the age of Hamilton twenty-five years after its première. Given the continued scarcity of Asian characters on Broadway stages, Song is likely one of the first many audience members will have ever seen, and Ha does not take that responsibility lightly. “We are the face and voice of all the work that the crew and creative team has done up to that point and it’s always important for me to hold onto the reason larger than myself that I’m doing this work,” he explains. “It’s about the representation and the narratives that I am reiterating on stage every night. It’s inviting—generally speaking white—audiences to expand their sense of humanity onto bodies and faces that do not look like their own, which is a practice that people of color have been doing their whole lives. I watch TV or stage and it’s mostly white people that I’m looking at, but I can still connect with them from a universal sense.”

In many ways, all of Ha’s life has led him to Song. Raised in Seoul and Hong Kong before his family immigrated to the American Northeast, he says he took to acting early as a constant in his life. “I had to very frequently find a new anchor in a new community or rediscover my identity or place in a community because I had to move a lot,” he says. “Perhaps performance for me felt like a staple, where I could drop the responsibility of figuring out where I was in that social space because I was told who I had to become for a role.”

He focused on Chinese and Korean language and culture at Columbia and wrote his thesis on social criticism in Chinese independent film and the oppression of artists in general under the Communist regime, which finds a parallel in Song’s tense interactions with Comrade Chin, who oversees his espionage while criticizing him for his bourgeois lifestyle and his general ineffectualness to the revolution as an artist. Ha also first encountered Edward Said’s Orientalism, the seminal study of the West’s centuries of patronizing, infantilizing, and colonizing the “East” through culture, military, economic, and social power, while studying there. “The idea of somebody putting a finger on and labeling this sense of otherness that perhaps I had been feeling growing up in predominantly white communities was refreshing,” he says. “It was empowering to know that it’s not just me, I wasn’t alone in this experience of being othered in ways that I couldn’t understand.”

In one of the play’s most powerful scenes, when Song takes the stand while on trial in a French court for spying, he speaks vehemently on several of Said’s themes, arguing that it was so easy to fool Gallimard into thinking he was a woman because Europeans are taught to think of Asians as inherently feminine. Ha, who calls Hwang an “outwardly political” and “Brechtian” writer, says he appreciates the opportunity to address such issues head on every night. “His politics and mine are exactly aligned, which is very fortunate,” he explains. “I get to speak directly to notions that the ‘West’ has towards the ‘East’ that apply to Asian-Americans as well, the preconceived notions, the prejudices or stereotypes that have always been placed upon me growing up and my Asian sisters and brothers. Turning that on its head and addressing it directly on stage is thrilling for me. Throughout the play, we see Song presenting a really three-dimensional, complex humanity that is not always seen with characters who look or sound like him, and that to me is so crucial.”

Such questions of diverse representation were front and center in the only other job Ha has had since graduating with a master’s in acting from NYU two years ago as well, as the understudy for King George in the original Chicago cast of Hamilton. Coming into a role originated on Broadway by Jonathan Groff and until that point played entirely by white men, Ha explains that he understood the importance of breaking yet another boundary in a show whose very premise is based on its racial casting. “It’s just the point of Hamilton that it would expand just another inch,” he says. “It’s like, Hey, we all know that these are dead white men that we’re talking about, but the story will not lose anything, and in fact the story will gain value, by having people who look like us performing and telling you these stories. It’s not that hard for audiences to accept that reality and get over that speed bump and then go along with and actually listen to what I’m saying and actually hear the music that I’m performing.”

In January, M. Butterfly and the current revival of Miss Saigon will both close on the same day, leaving another gap in Asian representation on Broadway. But Ha is hopeful that, beyond more Asian characters, one day Evan Hansen or the Phantom of the Opera could be Asian, without it being a notable event. “I would love to live in a world where people of color can do soap operas or just really cheesy rom coms and it’s not revolutionary,” he says. “I’d love for it to be commonplace. We’ll see if that happens anytime soon, but I can always strive.”

M. Butterfly continues through January 14.

- By

- Jonathan Shia

- Photography by

- Ben Lamberty

Hair by Yuhi Kim at Bridge Artists. Makeup by Misha Shahzada at See Management.