Raven Row and Paul Smith photography by David Grandorge. Juergen Teller studio and Cowan Court photography by John Dehlin.

6A ARCHITECTS

At some time over the last decade, history was extracted from the classroom and repackaged as an architectural motif. We live, work, eat, and drink among exposed brick, beneath open piping, atop repackaged wood, all dustless and polished. The past has been commodified, and the idea of history—that is, the feeling that you’re in it without knowing exactly what it is—is now the attraction, leaving us with redundant æsthetics and a void where the lessons true history can teach us would normally reside.

6a architects, the London-based firm founded by Tom Emerson and Stephanie Macdonald, doesn’t overtly reject this trend, but their highly intellectualized approach makes its shortcomings clear. Rather than dust off the bones of old institutions, they simultaneously surface the many forms of history within them—not just material, but also social and intellectual—and then find ways to record its ongoing passage. That their clients—Churchill College at Cambridge, the South London Gallery, Paul Smith, the Victoria and Albert Museum, and Juergen Teller, among many others—are well-positioned for this type of work is not a coincidence, but their effort to extract historical meaning where others would simply extract historical material is ultimately what drives the growth of their practice.

“We have never sought historic environments, they found us,” say Emerson and Macdonald, who started the firm together in 2001. “Sometimes, the richness of history is explicit in very fine architecture, like the original silk mercers’ houses which formed the basis for Raven Row”—6a’s well-known nonprofit contemporary art exhibition center located in Spitalfields, London—“but we’ve often found that the key to the place is a less visible and unrecorded social history: the lives of people and the fortunes and misfortunes of the city all leave traces.”

Their focus on uncovering the invisible is rooted in a sort of humble awareness that their projects—however grandiose and recognizable—are, in their own right, single points through which time passes within some broader grand narrative. They call it a need to “maintain the continuity of life” and, in that, to recover the lives that preceded theirs and record the lives of those around them, and then use that information to educate those who follow. “Making connections to the past through material or recording the future in it is not necessarily a responsibility, but it is an interesting tool with which to engage people,” the architects say. “We’ve spoken mainly about history, but our work is fundamentally about the future and enabling life to be useful, productive, and pleasurable for everyone. It is also good to be reminded that our projects will not be new for very long. Before we know it, they belong to the city or to the landscape.”

Raven Row is emblematic of their approach. Composed of two eighteenth-century silk mercers’ houses coupled with a concrete-framed office building built in 1972, the project is emblematic of 6a’s unique approach to coupling restoration with recreation. Charred timber rooflights allude to a fire that nearly destroyed the structure in 1972; doorknobs are marked with soft thumb prints, an almost eerie sign of the current inhabitants’ predecessors; and all furniture displays are freestanding, as they were in the eighteenth-century, when they would have needed to be moved to the nearest source of light or fire. Archival photographs, discovered in the London Metropolitan Archive, helped the team to connect elements that reflect the social, nonphysical imprints of the past.

“At Raven Row, the history was the most compelling element. Partly because the buildings are Grade I listed and one has to care for the [National Heritage List], but equally importantly, the recorded history could not, on its own, make sense of the past or of the future as a contemporary art space,” explains the duo. “We had to find a new narrative in the social history of the place through archive photographs and building archaeology to bring all the elements together, including the two elderly sisters who lived in the attic flat above the galleries.”

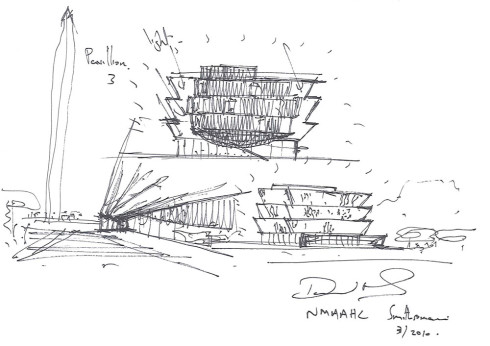

Last month, the story of Raven Row traveled to the Chicago Architecture Biennial, where sixteen architects have contributed a model tower or column as a hypothetical new home for the Chicago Tribune. In a multi-generational experience perfectly in tune with 6a’s multigenerational style, these contributions now stand alongside model towers produced during the actual competition to build the Chicago Tribune Tower in 1923, the winners of which—John Mead Howells and Raymond Hood—crafted the resulting building’s neo-Gothic design. Interestingly enough, a room from Raven Row was on display in Chicago during that competition, and the fact that “the carved wooden panels could have been on the same freight train to Chicago as the polemical Modernist competition entries arriving from Europe” has shaped 6a’s approach to the competition.

“We discovered that a rococo, timber-paneled room [of Raven Row] had been removed in the early 1920s—more or less simultaneously with the [Chicago Tribune Tower competition]—and had been shipped as an exhibit to the Art Institute of Chicago,” the architects explain. “It was brought back to the UK in the 1980s and stored in a barn in Essex until it was reinstalled in the original room in Spitalfields.” Their column will be copied from the rococo profile of the room now in situ at Raven Row, with each layer being a wooden section contributed by an Illinoisan wood turner, all synthesized into the form of the Tribune Tower.

“In the end, it is a playful take on these transatlantic exchanges, on history and on making. Each maker has sent us a photograph and biography so we can match the tower to people,” the architects explain. “Spitalfields and Illinois still in correspondence after nearly a century.”

For more information, please visit 6a.co.uk. The Chicago Architecture Biennial continues through January 8, 2018, in various locations throughout Chicago.

Raven Row and Paul Smith photography by David Grandorge. Juergen Teller studio and Cowan Court photography by John Dehlin.