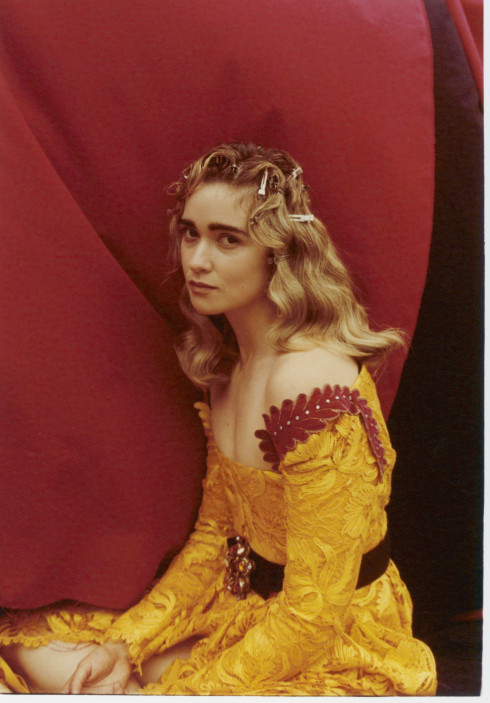

- By

- Gautam Balasundar

- Photography by

- Mark Squires

Styling by Nicolas Klam at Artists & Company. Grooming by Sara Denman at Celestine Agency. Stylist’s assistant: Lulu Zhou.

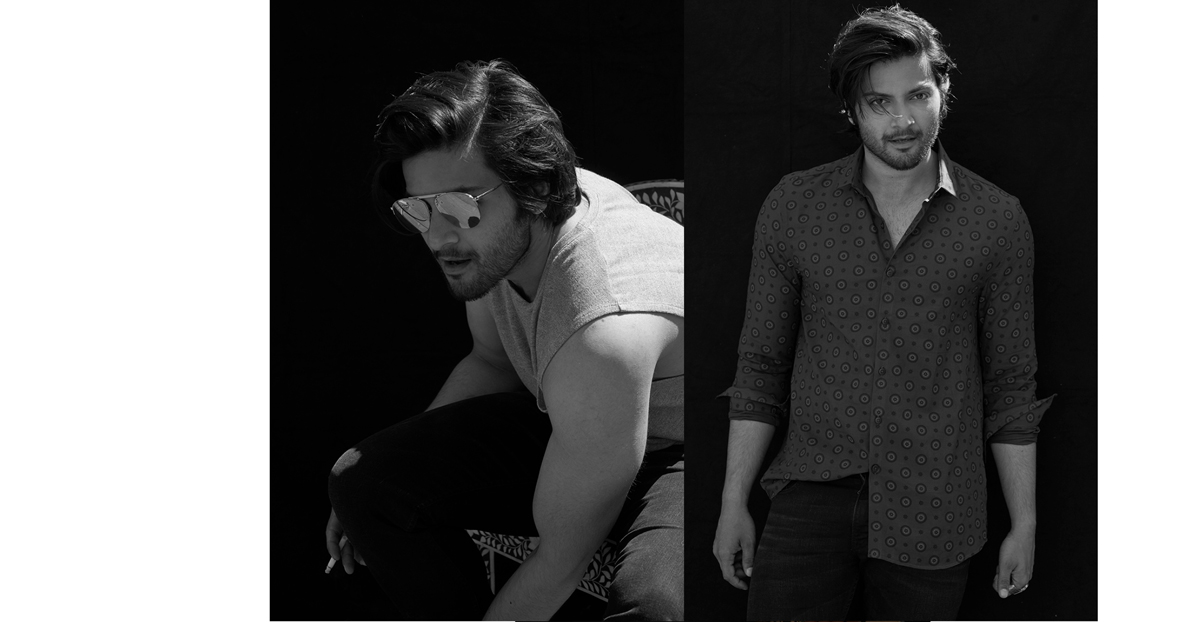

ALI FAZAL

At a time when people are so focused on borders, Ali Fazal has his sights set on bridges. A Bollywood star now making a major turn the West, he is set on bringing to his native industry the international attention it has not yet received. “There can be a huge cultural difference, but I think we’re starting to bridge that gap,” he says with confidence. “Because of Netflix and Amazon, everybody in India, all the movie buffs, suddenly we’ve been exposed to this side of the world.” With his new film Victoria & Abdul, Fazal is breaking down a longstanding boundary and building a bridge in its place.

While Victoria & Abdul, which spotlights the unusual friendship between Queen Victoria and an Indian clerk, serves as an introduction to Fazal for Western audiences, the thirty-year-old has already amassed a large following in India ever since breaking out in Bollywood, though that was never the plan. “I accidentally got into this,” he admits. “I used to play a lot of basketball and in tenth or eleventh grade, I busted my arm really bad. I was looking at making a career in basketball or in sports, and suddenly it just crashed.” His eventual path to acting was then the same as many of his Western counterparts. “I remember my friend came up and said, ‘Your English isn’t bad, why don’t you try for the Shakespeare?’ And I did. That feeling of being on stage was surreal.”

It didn’t take long for Fazal to begin getting roles, proof of his talents in an industry that often rewards connections over talent. “I’m grateful to everybody because Bollywood is a hard place for outsiders to break into,” he explains. “It’s a very close-knit group that’s not very nice to people from outside. And when I say outside, I mean families without a film background. There is a lot of nepotism there.” He had a small role in the 2009 IFC miniseries Bollywood Hero early in his career, but most English-speakers would only recognize Fazal from his part in the global blockbuster Furious 7. “It’s interesting that I started my career in Bollywood exactly the same way,” he says. “I did a cameo in this crazy big movie and it catapulted me into elite parts later, and of course today I’m in a nice space there.”

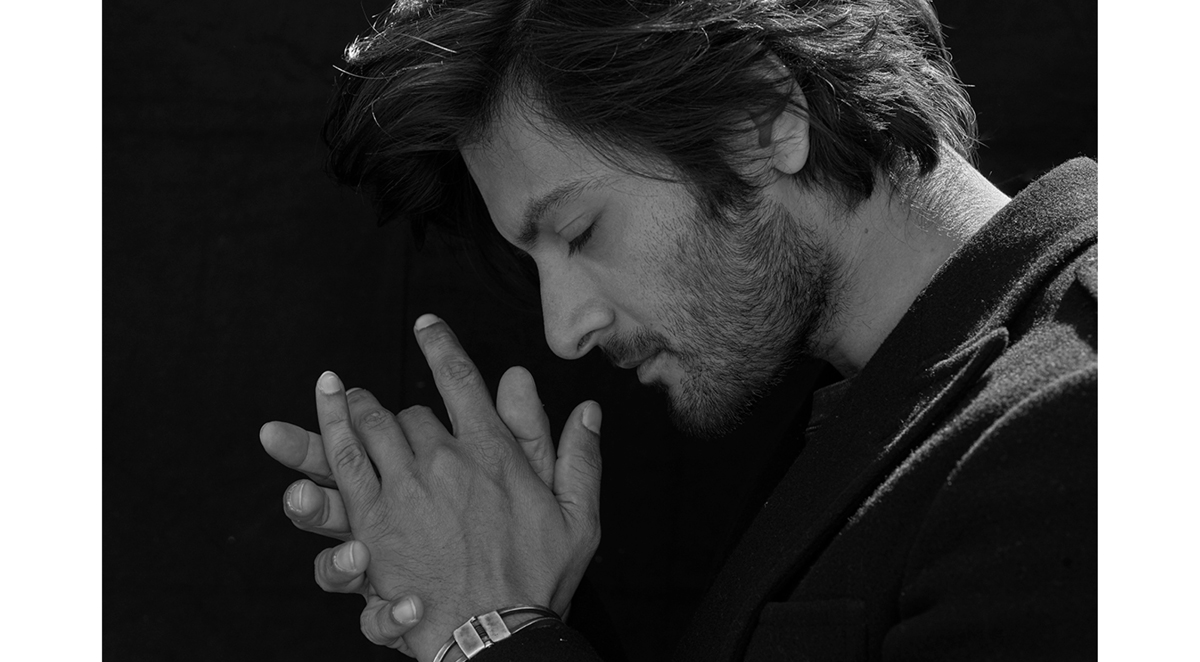

Victoria & Abdul serves as that major jump for Fazal, in one of the first English-language films headlined by a Bollywood star. Fazal plays Abdul Karim, the Indian servant—who later became the munshi, or language teacher—who formed a close bond with Queen Victoria (Judi Dench) towards the end of her life, much to the dismay of the rest of her family and staff. Throughout the film, the intentions of its characters come into question, and the culture shock of an Indian man serving as a royal aide brings out the underlying xenophobia. “It’s so weird that the story pretty much apes times today,” Fazal says. “It’s interesting how not much has really changed.”

Because Abdul was largely written off in the history of Queen Victoria—the day she died, he was kicked out of the palace and his possessions were burned—there was little material available in terms of research. In preparation for the role, Fazal read the few letters that were salvaged from Abdul’s correspondence with Victoria, but had to seek out other trace sources. “I read the letters, but there weren’t so many. I remember there was one autobiography of the Queen’s personal physician, and why I mention that is because that was one of the only mentions of Abdul,” Fazal explains. “There’s one chapter that was called ‘Munshi Mania,’ it’s almost like a film title. He mentioned the environment of the household while this man was there. It’s amazing to see that different perspective, the tension that was there when this man was a servant who was rising up the ladder and almost got knighted by the end of it.”

Abdul’s rise is a point of contention in the film, for both the characters and the audience watching. Director Stephen Frears deliberately offers a complex character whose motivations are never fully clear. Then again, the entire household sought to curry favor with the Queen and advance their own positions; it just happened that an outsider with his earnestness happened to do it better. “I think the best part that I found was that he resembled so many young ambitious and hopeful individuals in today’s world,” Fazal says. “This is a man who had an opportunity, who took that opportunity, came all the way to this unknown place, and survived this backlash.” In Abdul, Fazal saw that sincerity and ambition need not be mutually exclusive. “I liked the fact that he consciously looked past these cultural differences. He saw the good in things, and that was also his fault. He kept seeing the good in people and didn’t see the bad stuff coming and that punched him hard. It’s not a bad thing to be an opportunist—it shouldn’t be a negative word. For some reason it has a ring to it that is negative, it’s sort of conniving. Everybody’s doing the same thing.”

Still, Abdul proved to be a reassuring and genuine presence for the Queen as she approached the end of her life. “He saw this void and he sought to fill it up,” Fazal explains. “He saw this woman, bored from what he thought she definitely shouldn’t be bored by. She has everything, she was the queen of half of the world, empress of his own country. Here’s this first glimpse of one woman who’s bored out of her mind, and this protocol has become so mundane. So I think there was this spark. And you see how they intellectually stimulated each other.”

That bond raised more questions about the intimacy of the relationship. At times, Queen Victoria treated Abdul like a son, but the fact that he was a tall, handsome man was not lost on her. “It was a very unclear relationship,” Fazal admits. “The way she would sign off at the end of these letters, she would just throw you off. Some would say, ‘the Queen misses her munshi, come back dear friend.’ Some of them would say, ‘the Queen misses you, come back, hold me tight,’ and these are big words for a monarch. Another one would be ‘my loving son,’ so it was this weird sort of intimacy. The point was not to cage it in one genre, one heading. I think it was a mix of all of that.”

Though Fazal approached the project the same way he would any new script, he did recognize that he was appealing to a much different audience than he was accustomed to. “I wouldn’t say there is one particular way of acting out of two different kinds of cinema,” he offers. “It’s just a sensibility of knowing the audiences that you’re going to be reaching out to. I know that there might be a bunch of people sitting in Texas watching this film. I know that I have to find that balance between satisfying an Indian audience member and someone in China or wherever. Suddenly it just went global with this film.”

“I think the audiences also has a palate for different cultures now and that’s what’s going to make the difference.” With Victoria & Abdul, Fazal is both a harbinger and beneficiary of the increasingly diverse film industry, and it couldn’t be a better project to address that issue directly. “I think it’s so amazingly apt for these times, but I think it’s a great lesson,” he says. “As cliché as it might sound, love and hope are the answer to everything.” And, as he emphasizes cultural understanding, his foray into Western cinema continues to offer up new connections. “Last night I saw Detroit. It shook me up,” he says. “It just shakes you up. It’s another issue altogether, it’s far, far away from Victoria and Abdul, yet it addresses something very sensitive. It hits you because it’s still there, not because it happened in 1967, but because it’s still there. Not because it happened in 1885, but because it’s still happening.”

If his entry into Hollywood proves anything, it’s the value of an expanded perspective and a more collaborative and far-reaching industry. “Our films are films because of the times they’re made in,” Fazal explains. “They affect the times that they’re made in, and that is art. It is nice that the movies are opening up, that they’re diversifying and there’s acceptance. Art should never have a geography to it.”

Victoria & Abdul premieres this Friday.

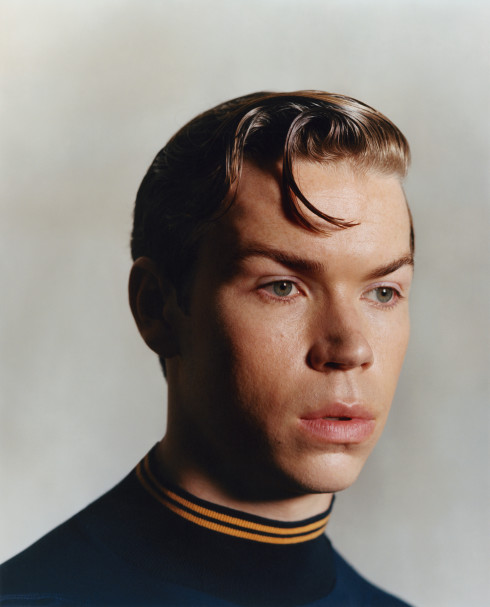

- By

- Gautam Balasundar

- Photography by

- Mark Squires

Styling by Nicolas Klam at Artists & Company. Grooming by Sara Denman at Celestine Agency. Stylist’s assistant: Lulu Zhou.