Photography © 2015 Matthew Murphy.

ANNIE BAKER'S 'JOHN'

The first thing that hits you is the matter. It’s actually physically difficult to really take in the sheer amount of stuff—figurines, pictures, dolls, mugs, and various other impedimenta—that litters the set of John, Annie Baker’s new play at the Signature Theatre. Right from the get-go, you get an eerie sense of the objects that adorn every nook and cranny as something more than set dressing. At once mystical and intensely claustrophobic, this feeling of being surrounded by a thousand silent observers, of presences and forces which surround and pervade us, yet which we can never quite lay hold of, is at the heart of this frustrating, unusual, and often remarkable new play by the Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright (for The Flick in 2014).

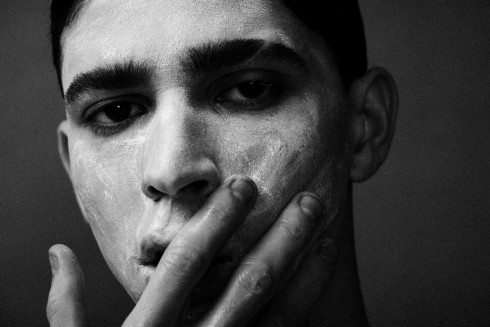

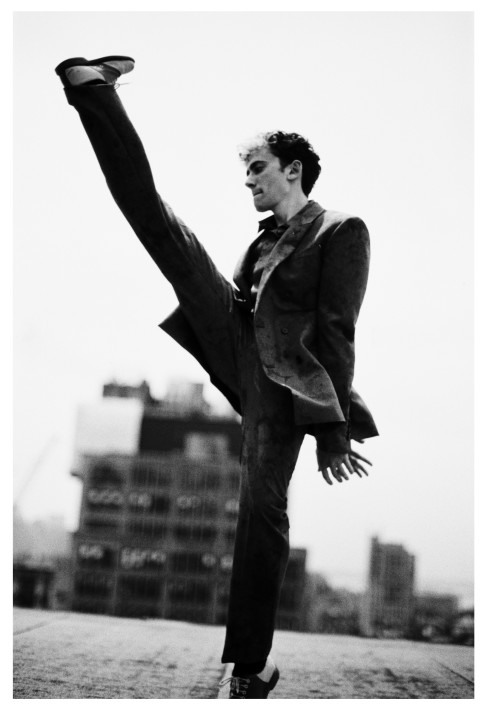

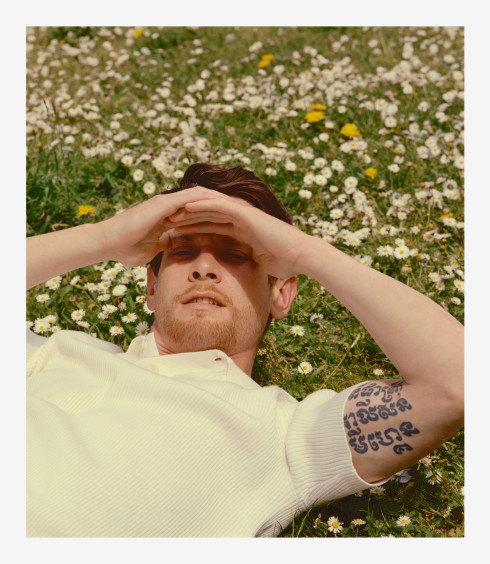

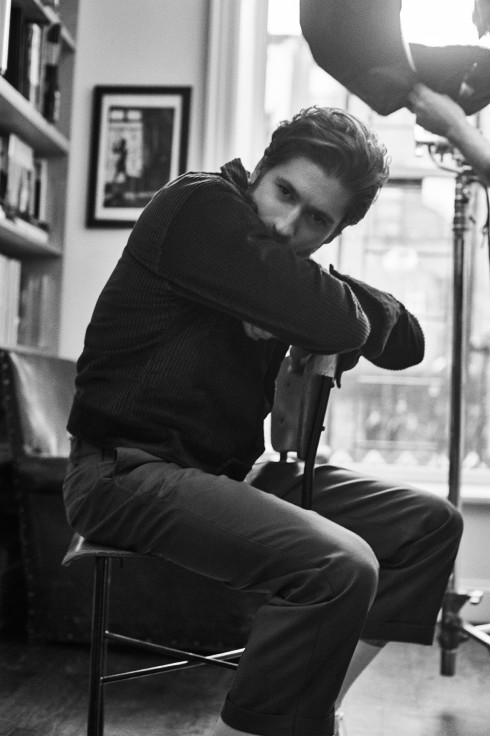

Directed by Tony-winner Sam Gold, the story places us in a quaint bed and breakfast in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, where Elias and Jenny, a couple of young Brooklyners sailing rough seas three years into their relationship, come for a few days’ tour of battlefields both historical and emotional. To them, as to us, entering the old house is like stumbling into some forgotten or half-dreamt world—a sense compounded by the sacred music that drifts like a musky odor from the old record player, and the uncanny congeniality of Mertis, their aged host who seems at times like a life-sized member of her own expansive doll collection. Over the few days of their stay, we eavesdrop on some cringe-inducing spats, a monologue recounting the seven steps of Mertis’ friend Genevieve’s descent into madness, and more than one unfinished ghost story. Love and jealousy are there, and betrayal, and maybe even hope—but the meticulously weird construction of the play’s beats, and the patient, precise direction turn what might be fairly ordinary dilemmas into something richer and stranger than it has any right to be.

What can be frustrating about John is that very few things ever rise fully to the surface. There are lights that flicker on and off, unelaborated references to odd goings-on in the spare rooms, frequent mention of characters who supposedly live in the house but never appear. We never shake loose a sense of everything being fuzzy, not just at the edges but at the very center, like a figure seen through frosty glass. Even fans of Baker’s style may find that the themes in the play keep a little on the windy side of coalescence. But the lack of clear connections, of Aha! moments and satisfyingly concrete revelations, is the very core of how the play works dramatically, and presents the patient theatergoer with unusual rewards.

The play’s texture, and the way it creates meaning out of experience, is almost less like that of a narrative drama than like that of a cabinet of wonders. Popular among kings, philosophers, and eccentric naturalists during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the Wunderkammer sought to collect under one roof all the strangest and most singular objects to be found, from taxidermied animals of exotic origin and scrolls containing magic spells to rare religious artifacts and even early automata. It represented an approach to the attainment of knowledge that runs counter to the deductive, systematic way we’re used to searching for meaning. Rather than tracing a few fundamental principles to their natural conclusion, the assembler of a cabinet of wonders supposes that if she collects enough of the things that make up the world, she will begin to be able to trace in them patterns so subtle as to normally remain invisible. The fundamental assumption is that the patient accretion of discrete objects (“matter,” as Genevieve would have it), will eventually bestow upon the viewer some palpable sense of the hidden forces that move around and within us. This is Baker’s method to a T. John is, in essence, a patient accretion of gestures and moments that in themselves are nothing particularly special, but taken as a whole and observed with patience, at last give us a flickering sense of something much greater. Concern for this sort of knowledge appears reflexively in the play, as well, as in Mertis’ recital of a long list of bird group names (“a wisdom of owls,” “an exaltation of larks”), Jenny’s talk about her job culling random facts for a quiz show, or the incantatory and indecipherable language that appears in Mertis’ journal and (one suspects not by accident) in her friend’s dreams during the depths of her madness. Baker weaves, through oddly echoed gestures, sounds, and words, an enormously fragile web of connections, never strong enough to constitute a clear sign but occurring too often and too oddly to be coincidence. It is often like trying to make out a signal sent from a sunken ship. But what signal could be more interesting to decrypt?

The performances are solid all around, with Christopher Abbott and Hong Chau firmly in control of their parts as the young couple, and Georgia Engel as Mertis leaving you guessing for a moment before you realize just how complex a performance she’s giving. On his umpteenth turn at the helm of an Annie Baker play (Circle Mirror Transformation, The Flick, etc.), Sam Gold calibrates the play’s wide range of expression like an artist working with familiar materials. The infamous pauses do not go unfilled, and the near-constant funereal underscore has a weird way of turning scenes that could be overdramatic into conversations we’re open to hearing. The characters of Mertis and Elias in particular are intelligently drawn by Baker, and part of what makes so long an evening (three hours, fifteen minutes) go by with no sense of the time is Baker’s talent for keeping one step to the side of the beat we expect. She gets sad when we didn’t think we were heading for sad, crafts some paralyzing moments of suspense, and is not at all above a farcical scramble to get breakfast on the table, to the accompaniment of an imbecilically eager player piano.

Not everything works in John, and an audience member would be well within rights to want more as the curtain falls. More clarity, more resolution—more brevity I certainly heard requested. But Baker is, in this piece more than any other she has written so far, an odd mixture of scientist and alchemist. In respect of the former, her experiments must often fail, dealing as they do with the intangible and having as their goal the quite possibly impossible. As a scientist, she has to contend with the fact that even those experiments that succeed do not always yield sexy results. But with drama, as with science, it is not always the sexiest, the most exciting, or even the most entertaining thing that ultimately reveals to us something truly fundamental about our world or ourselves.

John runs through September 6 at the Signature Theatre, New York.

Photography © 2015 Matthew Murphy.