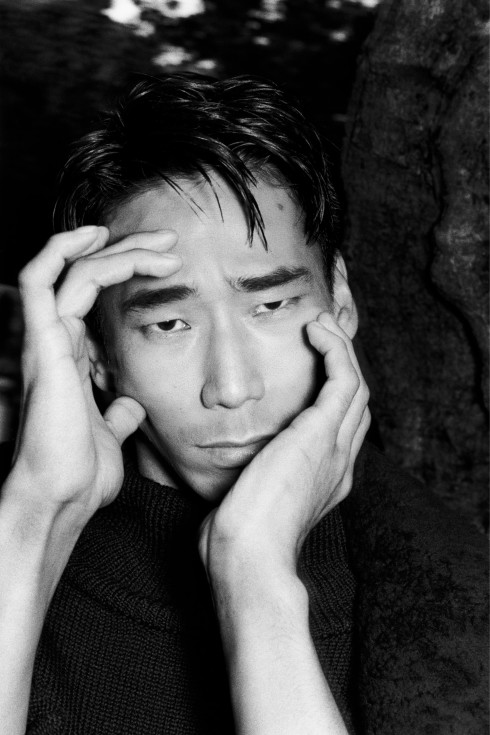

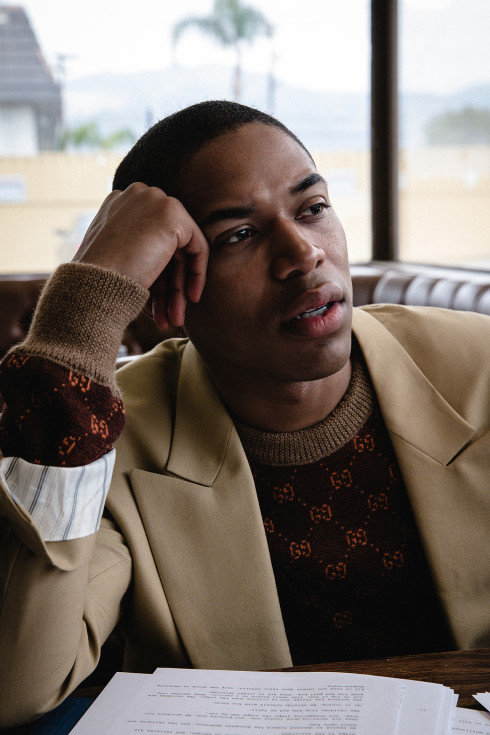

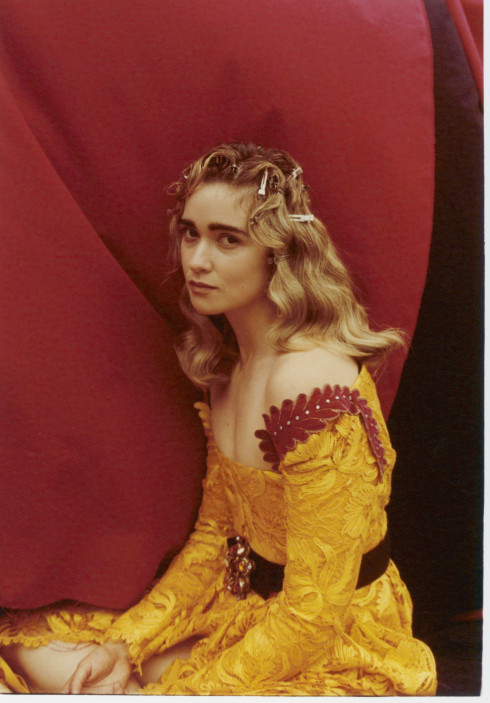

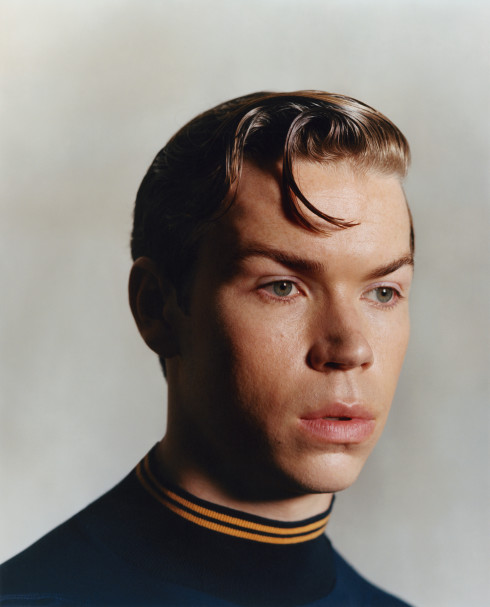

All clothing throughout, Carpignano’s own.

- By

- Jonathan Shia

- Photography by

- Lucas Cristino

Grooming by Jakob Sherwood at The Wall Group.

JONAS CARPIGNANO

In A Ciambra, the new film from the Italian-American writer and director Jonas Carpignano, it can be difficult to differentiate between fact and fiction—which is exactly the point. A coming-of-age story focused on Pio Amato, a young Roma boy who tries to take on the responsibility of providing for his sprawling family after his older brother is arrested, the movie is based mostly in reality and features a large cast of nonprofessional actors playing versions of themselves. As with his 2015 début Mediterranea, about African migrants forming new lives in Italy, Carpignano spent months in preparation before writing the script for and filming A Ciambra, although he is reticent to describe it as “research.” “For me, the research process was going to dinner there five nights a week or hanging out with the kids when they were playing football or going grocery shopping with the family,” he explains of the film, which was shot in the Amatos’s actual home. “I was at every baptism, I was at every birthday party, I was doing everything with them—but as a participant and as a friend, not as someone doing research.”

Carpignano, who is thirty-four, became close with Amato and his family while shooting an earlier short film, also called “A Ciambra,” as he waited for Mediterranea to come together. Amato played a supporting role in Mediterranea, which premiered at Cannes and earned Carpignano the prize for Breakthrough Director at the Gotham Independent Film Awards, and the new film is a sequel of sorts, but with the focus shifted. Barely a teenager, Pio’s livelihood in A Ciambra is based largely on various low-grade transgressions—burning copper for sale, swiping luggage off trains, ransoming stolen cars—but the story is less a crime caper than a tale of growing up. “He’s hit adolescence and adolescence is impossible to predict,” says Carpignano of Pio, who glows with impish charisma. “He’s still very much the person that you see him becoming. It’s unpredictable, but that’s just because adolescence is so unpredictable.”

That unpredictability is exactly why Carpignano, who was raised in New York and now makes his home in Gioia Tauro in Calabria, where both of his films are set, decided to make feature films instead of documentaries, even as they remain so heavily grounded in real life. “The thing about documentaries is you go in thinking it’s going to be something and then the documentary you come out with at the other side is completely different because you let the story and the characters and the place take you in a certain direction,” he explains. “We do that to an extent, but on the other hand there’s also things that I’m very interested in exploring that I don’t want to let go.”

Carpignano’s dedication to authenticity required working within a close-knit community that, given the long history of discrimination against the Roma in Italy, was not accustomed to close encounters with outsiders. He hired local residents to work as extras and on the crew whenever possible and says that the few disruptions they did encounter—including bottles of water poured into their generators—were often the result of jealousy over which families got to participate the most. Still, Carpignano, who has been around cinema his entire life thanks to a grandfather who was in the industry, admits there were challenges. “There’s a lot of things you can’t control when you change rhythms to adapt to a place that’s never made a film before,” he says. “You have to throw the rulebook out the window and have people around you who are willing to go with the punches. But at this point, I kind of love that. I’ve never done anything else, so for me that’s the adventurous part.”

Both A Ciambra and Mediterranea focus on marginalized groups and Carpignano admits that his own biography growing up biracial between the United States and Italy was part of what attracted him to these stories, but he insists that he feels more motivated by a drive to expand the scope of the country’s identity than any personal history. “When you look at Italian cinema, these perspectives have never been given the same amount of weight as a traditional, white Italian story,” he explains. “If you think of what Italian cinema has done, the image that people have of Italy right now is very much attributed to what Rossellini said Italy was after the war, so the national image is very much constructed through cinema. If cinema is really going to give an accurate portrait of a nation, I think it’s important to show what is happening to new black Italians or Romany Italians and show that there is a richer and more complex social fabric than Italian cinema has put forth this past century.”

A Ciambra, which lists Martin Scorsese as an executive producer, won the Europa Cinemas Label Award at Cannes last year, and Carpignano has been nominated as Best Director at this year’s Independent Spirit Awards. (Mediterranea was nominated for both Best First Feature and Best First Screenplay in 2016.) The film was also Italy’s official selection for the Oscars this year, a bracing sign of support from the official moviemaking community even if it ultimately did not receive a nomination. “The goal is to say there are other voices, there are other people, there are other ethnicities that make up Italy,” Carpignano says, “and the fact that the country decided that this is very much the story of Italy means that it’s working. It means mission accomplished in a small way.”

Carpignano, who was based in Rome for several years before moving south, is now at work on the final film in the triptych, which he says will focus on an ethnically Italian family in the same city of Gioia Tauro, bringing the story of assimilation and integration full circle. The upcoming movie promises to be as firmly rooted in place and reality as his first two while adding in another perspective to his intermingled vision. “All these films in one way or another talk about why people stay, why people live in Calabria, why people don’t move, why people choose to plant their roots, and this next chapter looks at an Italian family that’s lived in the town for generations,” he explains. “It’s about their relationship to the town to show why people are so drawn to the place and why people feel allegiance to the place where they live.”

A Ciambra is out now.

- By

- Jonathan Shia

- Photography by

- Lucas Cristino

Grooming by Jakob Sherwood at The Wall Group.