- By

- Zachary Sniderman

- Photography and video by

- Jacob Sutton

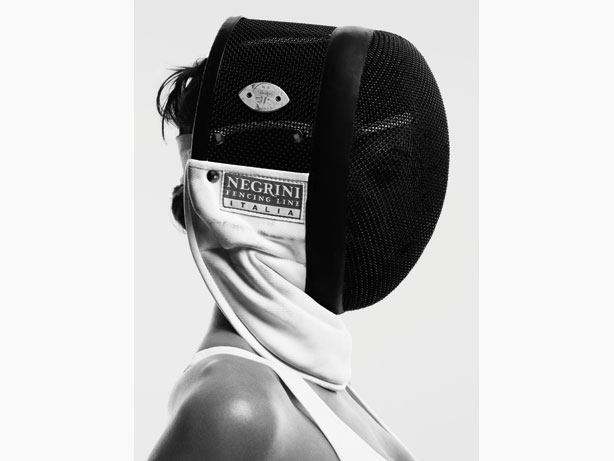

NATHALIE MOELLHAUSEN

Just hearing the details of Nathalie Moellhausen’s jet-setting month, you’d think she was living a glamorous red-carpet life: Brazil, Cuba, a week in Europe, Nanjing, Sydney, and now Paris to “decompress.” The reality is that Moellhausen is dead tired from traveling from one exotic gym to another, training for a series of megawatt competitions that will dictate whether she finally makes it into the Olympics.

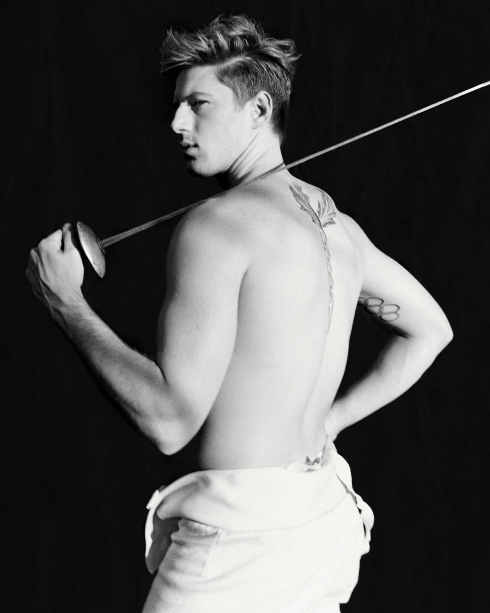

Moellhausen is one of Italy’s premiere fencers, and a gold medalist in épée—the most creative, erratic, and unpredictable type of sword—at all three major European fencing tournaments. Épée, unlike the other two styles of fencing, foil and sabre, is a total crapshoot. The whole body is fair game and there is no formal “right-of-way”—any hit is a good hit.

Épée, like Moellhausen herself, is a little mercurial. “It’s the ugly duckling of the bunch,” she says. “It’s undisciplined and everything is possible. You can be world champion one day and the day after you can lose to someone who has no idea about taking the sword in his hand.”

However, Moellhausen, 25, is anything but an ugly duckling. Lithe, sharply attractive, and gracefully athletic, she embodies fencing’s stereotype as a balletic sport producing fiery, albeit erratic, talents. She began fencing in Italy when she was five, using the sport as a way to still her wayward spirit. Moellhausen joined the local club and made fencing her life. She spent much of her time in Italy despite a background as extensive as her recent travels. Moellhausen was born in Brazil and is half-Brazilian on her mother’s side. Her father is German and lives in London.

That background has put Moellhausen in a strange spot, especially with the Olympics looming large. What country has her loyalty? Where does she belong? Moellhausen may be as international as they come, but she feels proudly Italian, especially when it comes to how she competes.

That choice, however, wasn’t simple. Italy has perhaps the longest and most illustrious fencing history of any country. There is a long lineage of Italian greatness in fencing, yet the pressure doesn’t weigh too heavily on Moellhausen’s mind. Italy is known for turning out foil champions above all else. Épée, a recent addition to the Olympics, has almost zero history, especially with females. Moellhausen is cutting her own path as one of the first Italians to even medal in épée.

Watching Moellhausen fence is a lot like watching a cat-and-mouse game. In one match from 2010 in Budapest, Moellhausen tries to bait her Ukrainian opponent into lunging first. Both fencers bounce and shuffle, jabbing the air with their swords to trick each other into committing a mistake. In an instant, Moellhausen closes the distance and lunges high, but her opponent drops to her knees and scores a hit. She lets out a cry and reflexively grabs her blade, bending it straight for the next attack. Moellhausen, restraining her agitation, walks back to her starting point.

This is indicative of the old Moellhausen, the aggressive fencer pushing her opponents with attacks. The Italian school of fencing focuses on creativity and aggression. “I feel Italian in the way that they are creative,” she says. “They like to be a little bit crazy.” Moellhausen has tried to combat those tendencies by moving to France to learn the French school of fencing, designed to defeat the attacking Italian style. It focuses on lures, feints, and exposing gaps in an opponent’s attack. The best offense is a good defense, if you will.

Another match from a 2010 tournament in Paris shows Moellhausen fencing “French.” She teases her opponent, a highly-ranked Polish woman, into attacking. Moellhausen sways out of reach and tags her on the arm. Moellhausen rocks back on her leg and fist pumps. Most fencers are quick and agile, Moellhausen especially so. She is a hair smaller than her competitors but makes up for it with speed, deception, and athletic improvisation. Moellhausen wins another point, tagging her opponent on the leg when she overcommits. The two set up for a final pass. Moellhausen jabs and retreats as she has all match. She launches forward, scoring a clean and convincing hit on her opponent’s chest. All Moellhausen’s pressure is let out as she whips off her mask and throws up her arms in victory.

“When I arrived in France, I always wanted to attack but with no clear idea,” Moellhausen says. For her, the hardest part of fencing isn’t the techniques or the physicality, but managing frustration and mental pressures. Moellhausen has been working with specialists to help with her breathing and concentration, so as to allow her to keep her mental edge and up her game. “Fencing for me is like body language,” Moellhausen says. “It’s like a conversation between two people. In real life, if you’re dominating a conversation, you know.” She compares fencing to physical chess.

Clearly, the path hasn’t always been easy. “When I was young, I used to feel like I had more talent than I do now, where I’m more conscious of what you have to do,” Moellhausen says. So much of fencing happens in a chaotic instant when someone decides to do something—feint or attack—that any doubt or errant thought can easily lose the match. The goal is to learn as much as possible and then be able to act on impulse in the moment. That sort of felicity isn’t easy and it also isn’t about how fast you can move or how many sit-ups you can do. It is, however, crucial to Moellhausen’s future success.

As much as Moellhausen is fighting to qualify, the sport of fencing is fighting to stay relevant. To the untrained eye, fencing is a real disappointment to watch. People expecting swoops, jumps, and flashy swordplay are instead met with a lot of waiting and then a moment of indiscernible action at which point someone wearing an opaque helmet screams and another person wearing an opaque helmet walks away in anger. Moreover, it’s difficult to explain that, sure, that person hit first but he had not properly established right-of-way and therefore lost the point. Fencing’s highly formalized rules have made it difficult to gain mainstream popularity. The sport, in general, is in decline.

The ability to fence was once a prized social ability on par with musical aptitude, gentlemanly status, and knowing which fork to use. Now, however, it is basically non-existent in the West save for the Olympics, its one televised moment of glory. “For us, the Olympics is like our red carpet and it’s every athlete’s dream to parade there,” Moellhausen says.

Her absence from the Olympics thus far is something that does weigh on Moellhausen’s mind. For all that fencing has given her, she is determined to give back. In 2008, she created the Skirmjan Project, a melding of fencing with contemporary art. She created the project after she learned she had not qualified for the Beijing Olympics. In 2010, the project performed a choreographed routine using swords at the opening ceremony for the World Fencing Championships at the Grand Palais in Paris.

“This is the idea, to be in the present when you fence,” Moellhausen says. “You used to fence with your mind in the present because you could die…When you fight each other you cannot doubt, you cannot have any hesitation because then you’re going to die. [Now] we get so stressed about ‘winning.’”

But Moellhausen will need to keeping winning if she stands a chance of making the Olympics. There are several major tournaments where she and the rest of the Italian team need to rank within the top four teams in the world. Right now they are ranked fourth, but that could easily change with a mistimed attack or a mental slip.

At some point Moellhausen will stop. She’d like to have kids and continue to make art through the Skirmjan Project. Despite the siren call of a “normal” life, Moellhausen’s only focus for the next months is to remember everything that has brought her to this point—the training, her country, the waning legacy of her craft—and the moment she picks up her sword, to forget it all and just fight.

Styling by Tracey Nicholson. Makeup by Kay Montano at D+V Management using Chanel. Hair by Malcolm Edwards at D+V Management using L’Oréal Professional. Manicure by Jessica Hoffman. Photographer’s assistants: Nathan Hudson Jenkins, Billy Ballard, and Katrina More-Molyneux. Stylist’s assistant: Beatrice de Cossio Dominguez. Hairstylist’s assistant: Gerard Hawe. Production by Grace Holbrook at D+V Management. Retouching by Henhouse. Digital capture by Claire Fulton at Spring Digital.