- By

- Jonathan Shia

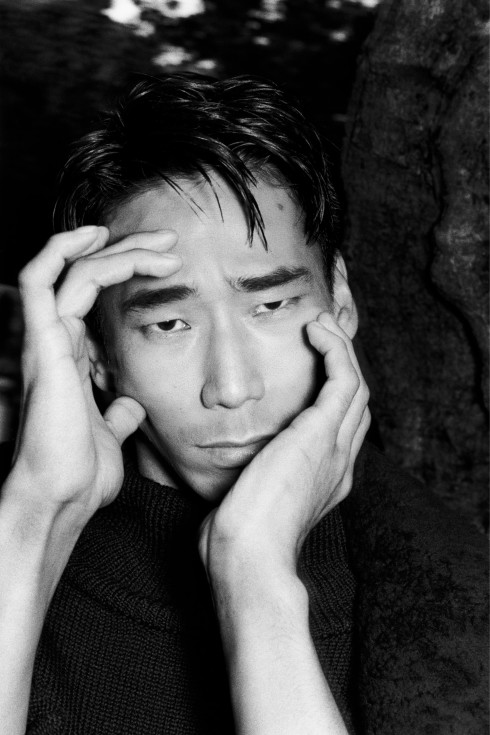

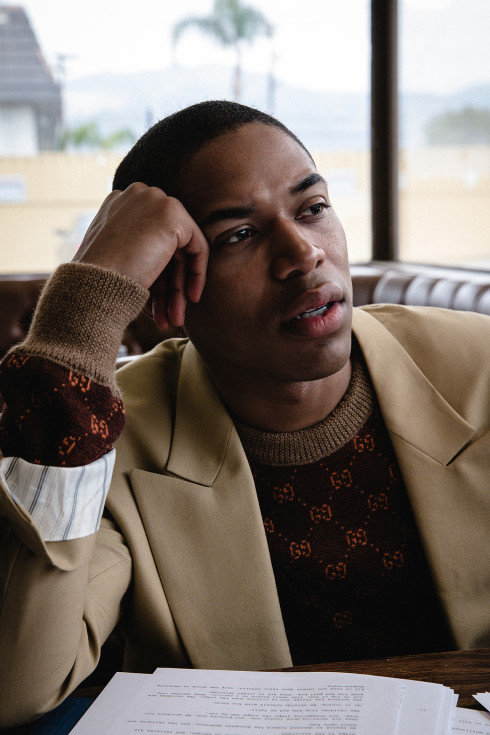

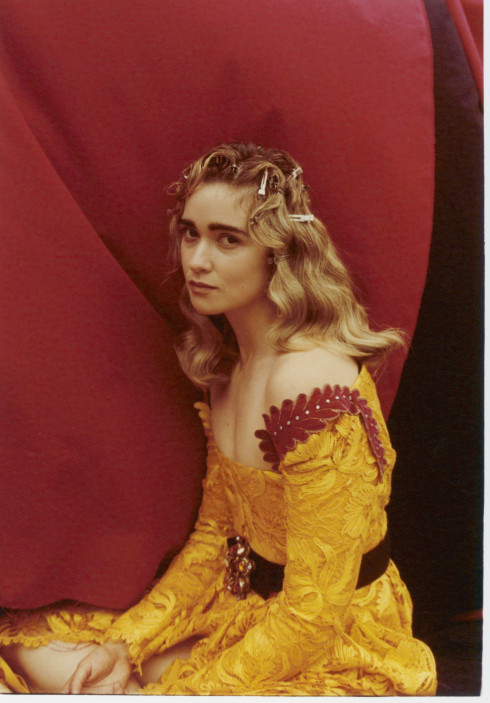

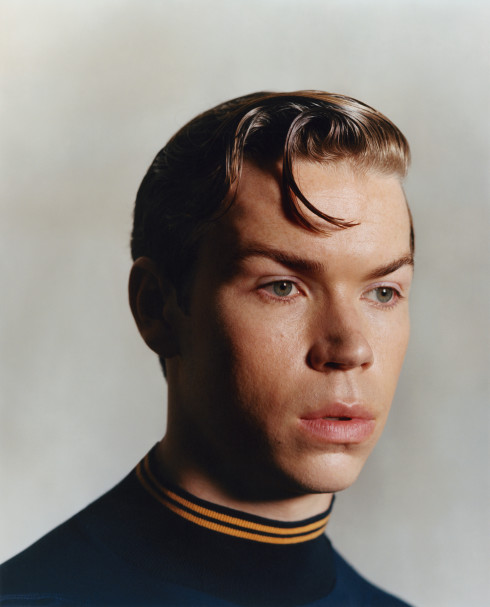

- Photography by

- Chandler Kennedy

- Styling by

- Jordy Huinder

Grooming by Walton Nunez at The Brooks Agency.

RaMell Ross's Oscar-Nominated First Film Reframes the Black Experience

Amid the mess of this year’s Oscars, with endlessly shifting categories, hosts, and musical performances, the films themselves have been getting a little lost, which is especially unfortunate given the historic firsts—Spike Lee’s first nod for Best Director, Black Panther becoming the first superhero film nominated for Best Picture—and the strength of some often-overlooked categories like Best Foreign Language Film. Both a first and regrettably neglected is RaMell Ross’s Hale County This Morning, This Evening, an entrant in the Best Documentary category that marks the director’s feature film début. Lyrical, incisive, and exquisitely graceful, Hale County is more tone poem than documentary, tracing the course of five years in the lives of two young black men and their families in the eponymous Alabama region.

Meandering in its structure and rejecting most of the hallmarks of typical documentaries like talking heads or data points, Hale County was, Ross readily admits, a long shot for a nomination in both its æsthetics and its themes, which is what makes this accolade particularly invaluable. “It’s meaningful, not the act of being nominated, but that so many people in the doc community thought the ideas in the film were valuable enough to be publicly heralded,” he explains. “It’s strange because the film is almost hyper-consciously about the centrality of the black experience. For that to be validated, one, as a documentary, and then also through this whole process, I think is the most meaningful thing.”

In less than eighty minutes, Ross’s gently roving camera introduces us to Quincy Bryant and Daniel Collins, two lifelong friends making their way through new families, college basketball, and young adulthood as black men in the American South. At a time when race relations are a defining issue of our society, Hale County avoids flashpoints like police brutality, mass incarceration, and economic inequality, making an ultimately more powerful statement about the black experience by insisting on its worth at a fundamental, existential level. “It is unfortunately trendy, meaning that it wasn’t considered popularly on this scale before—and hopefully it’s not a trend,” he says of his central focus on African-American life, “but how the film is separate is it’s not trying to do that; it’s doing that by default. It’s filming from the centrality of it like, ‘There’s nothing else; this is my perspective and it is the black experience,’ not, ‘This is the black experience. I feel like that’s what we all forget being stuck in our points of view is that it’s the default for us. So how do you make the black experience the default? Let someone else know that this one is universal in this place.”

Ross’s emphasis on particularity and ephemerality is part of why Hale County, and its blessing by the Academy, is such a groundbreaking surprise. Bryant plays with his son Kyrie and Collins shoots hoops at the college gym, but the film is less about story than mood, offering a peek into everyday life in a world that is far removed from that of the traditionally older and largely white audiences who flock to documentaries. Ross admits that the milieu he found in Alabama was unfamiliar to himself as well, as a Northerner who originally moved south to work with a local organization to teach photography and coach basketball. Hale County is about the process of discovery then, both for the viewer and for the documentarian. “I think that this is what was interesting to me about pursuing the film with this specificity,” he explains, “like what’s the perspective and the perception of the South as a black man returning from the North, considering the South as a conceptual home for the black image and this cul de sac of the black American experience? I only knew it through Richard Wright, I only knew it through Forrest Gump, I only knew it through the almost erasure of true slavery in textbooks. What’s my connection to it? I didn’t know much, but I wanted to learn through looking.”

Just as Ross, now thirty-six, had not originally set out to make Hale County, filmmaking was not always where he envisioned himself ending up. Originally at Georgetown on a basketball scholarship, he shifted his focus to photography after being sidelined by a series of injuries. “That being the only thing that I knew until that didn’t happen, I always was aware of deconstructing the why and the how,” he says, “and that critical lens lent itself to continuing to move through modes of making in photography and then to film.” His photography has since appeared on book covers, at New York’s Aperture Gallery, and in the pages of Time, Harper’s, and the New York Times, and he says the progression into film for Hale County felt entirely natural. “One failure of photography is to reproduce the moment to the sufficiency of the actual moment—take a picture of a sunset and it’s never that, it’s way grander in real life,” he says. “Being in the South and having the historical connection to it and seeing simultaneously how disenfranchised folks were but also how beautiful the place was and then considering all the popular renditions of the space, it seemed like there was this huge absence of what it was like specifically, contemporarily.”

When Ross decided to start filming in 2012, he says he settled on Bryant and Collins as protagonists because he already knew them so well as friends: “I think because our relationship preexisted the film, it was just another way to continue hanging out more intensely more than it was to actually make a film.” He took his small DSLR along to family gatherings and basketball games and in the backseat on car rides, gathering over thirteen hundreds of footage he then proceeded to edit down. When Hale County premiered at Sundance last year, Ross says Bryant and Collins were “almost moved to tears” by the film and the reaction it received. “The best way I could explain it, because it’s so strange, is it would be like having a diary of moments that you don’t remember shot by someone who has a perspective that you’re unfamiliar with in a beauty that is uncommon, elevated to the space where you watch BlacKkKlansman,” he explains. “They’re in an auditorium with hundreds of people who see those moments in the same deified space as cinema. They’re less people and more characters and figures and protagonists.”

With its success, Hale County forces a reconceptualization of black roles in the documentary field, which until now has focused largely on athletes, civil rights activists, or criminals. As a professor at Brown, Ross says he is hopeful for the future when he discusses the issue of representation with his students, emphasizing that diversity is just as important in true-life stories as it is in fiction. “For me—and I know for a couple people who are very conscious of the way in which marginalized communities are represented and who’s representing them—it means that the documentary genre is finally having a mirror put up to the way in which it’s represented truth and its feigning of objectivity and its peddling in fantasy of universal truths of what lives are like,” he explains. “I think the most interesting part is that people feel close to Quincy and Daniel and they feel like they know them, but they don’t say much and they’re not in it much. It’s possible to understand someone’s life and someone’s humanity and someone’s struggle without these more traditional and voyeuristic means and all of these tropes that we use or we think are the avenues to truth. It’s great for the doc space. I think it makes the doc space aware that when you give cameras to people in the communities and they’re prepared to use them correctly, the world’s better and the results are more interesting.”

Hale County This Morning, This Evening is now available in digital release.

- By

- Jonathan Shia

- Photography by

- Chandler Kennedy

- Styling by

- Jordy Huinder

Grooming by Walton Nunez at The Brooks Agency.