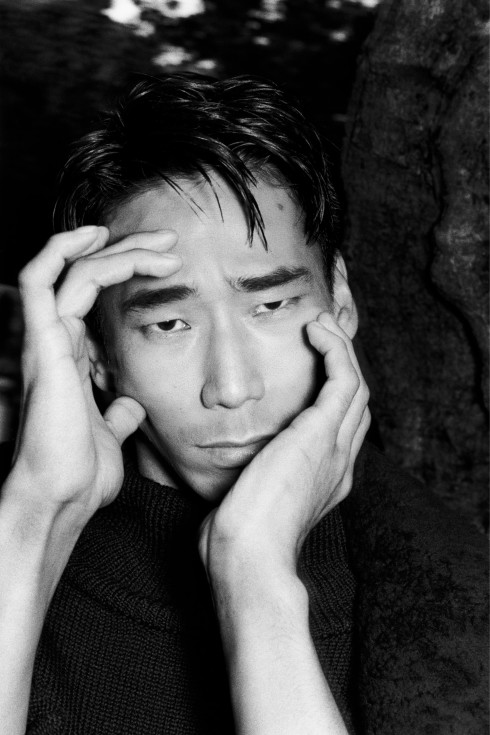

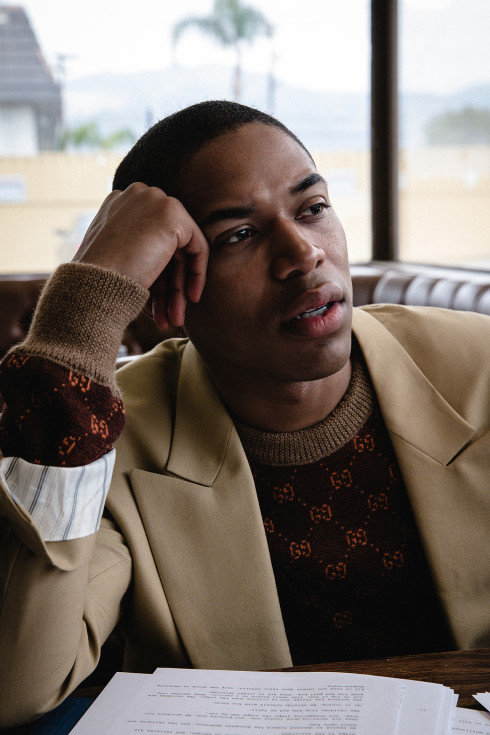

- By

- Jonathan Shia

- Photography by

- Adrian Gaut

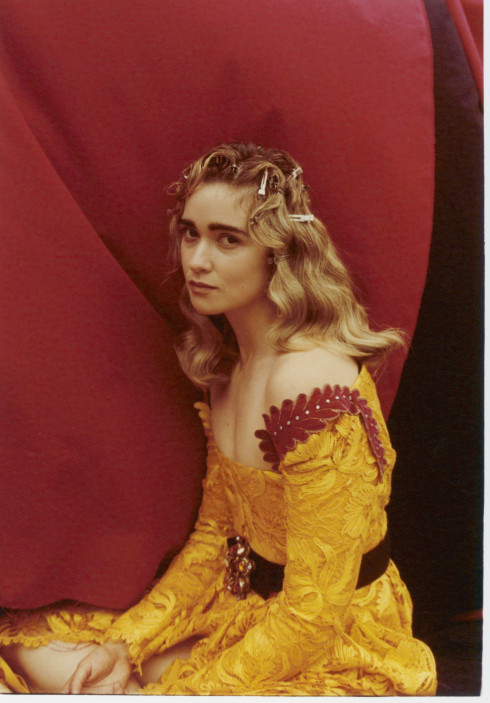

DENIZ GAMZE ERGÜVEN'S 'MUSTANG'

The French-Turkish director Deniz Gamze Ergüven’s stunning début feature film, Mustang, opens on a textbook example of idyllic youth. On the last day of school, students bid a teary goodbye to a beloved teacher before taking to the beach for an afternoon of play, the young girls riding on their classmates’ shoulders as they try to push each other off into the water. Washed in a golden light, the children are exemplars of innocence, laughing and splashing their way into their summer holiday.

When the five sisters at the heart of Mustang return home, however, they are accused of sinning, punished one by one by their grandmother, who has learned through a meddling neighbor that they have been “rubbing themselves” on the boys’ necks. Thus begins the gradual lockdown of the girls within their own home, where, overseen by their grandmother and uncle as well as a handful of other relatives, they find themselves suppressed and subdued, the bars on the windows and the high fences forming a literal prison. “I wanted to tell, with quite a sense of urgency, what it is to be a girl in Turkey,” explains Ergüven. “There was something which felt really striking, which was the filter of sexualization through which women are perceived. In a way, every single action that women do, every single inch of skin is considered through that filter and it’s an attempt to put them in a specific place in society. It starts off at a very early age, that sexualization, and it’s as if someone had pressed a button. There was a before and an after, and from a moment in preteen age, things change.”

That sudden shift, which leads eventually to a heightened effort by the adults to marry the sisters off one by one—often through arranged marriages—comes as a shock to the girls, who are throughout lively, headstrong, vibrant, and independent. Mustang is told from the perspective of Lale, the youngest, played by Gunes Sensoy, who, like three of the other four young actresses who carry the film, was brand new to acting, and the result of nine long months of casting. “We had many diagonal relationships that had to exist through the group, so it was a very delicate equilibrium,” says Ergüven of finding her five powerful leads. “For months we tried one combination after another and eventually it clicked magically. They had a very strong antagonist. They were fighting back very solidly together and they would protect each other, so it was quite beautiful.”

That antagonist is nominally their uncle, who represents the traditional patriarchal views of the small town in Turkey’s Black Sea region. After that opening burst of freedom, the sisters are virtually confined to their house, forced to wear long, unshapely dresses in unflattering colors while they learn to prepare food for their future husbands in what Lale calls a “wife factory.” The decision to focus on the perspective of the sisters was, for Ergüven, one with both national and broader art historical implications. “I really have the impression that the perspective of women [in Turkey] is completely unknown and completely exotic, not only for people who are watching the film on the other side of the world but literally for the male counterparts of these girls,” she says. “Art history and cinema history have always been through the eyes of men. Women are always objects and never subjects—of their hopes, desires, aspirations.”

Ergüven, who spent her youth between Paris and Turkey, says the film has been met with a strongly polarized response in Turkey (where it was released last month), no surprise given its controversial and rebellious spirit. “All the reactions have been really extreme,” she says. “On one hand, you had a real pure love and the adjectives used for the film were all extravagant, and on the other hand, people who felt antagonized by the film or didn’t like the film for one reason or another just did the same in a negative way. There was absolutely nothing in the middle.”

Some of the reaction, in fact, has gone so far as to decry the film—and the filmmaker—as foreign, an outsider not reflective of the nation as it sees itself. “People would say, ‘She’s not one of us,’ because I’m Turkish-French,” Ergüven says. “In a sense, I guess the film has its very own language and it has its very own distance from reality. Turkish films at this point are quite homogenous in style, but there’s something very Turkish for me in the fiber of the film.”

In September, Mustang, already a hit at Cannes earlier this year, was selected as France’s submission for next year’s foreign-language Oscar, a stamp of approval that Ergüven says reflects the inclusive spirit of her adopted country. “It’s a modern, very radical way for France to assert the diversity of French cinema,” she says. “France is a country which is traditionally very open and curious about embracing different forms of cinema. French audiences go to see films in their original languages with subtitles. From the moment we walked out of post-production, there was no differentiation between our film and any other French film.”

France choice of Mustang also unexpectedly took on renewed resonance with the recent terrorist attacks in Paris, an assault on the everyday and nearly banal pleasures of contemporary youth, from concerts and cafes to soccer matches, as the political discussion across Europe swings back and forth again between open-mindedness and a fortress mentality. Ergüven notes a similarity to the suicide bombing of a peace rally in Ankara earlier this autumn that killed nearly a hundred people, many of them students. “‘Each time, it’s just kids having fun, so it’s really an attack on not only everything that we are, which is people aspiring to freedom, but the fact that it is an attack on young people, for me, they’re attacking the holiest thing in our society. Every single hair on all of those kids’ heads is holy, every exchanged look they can have with a loved one is holy.”

Speaking of the twisted ideology of the terrorists, she continues, “It’s a reading of society—maybe it’s the same one in the film—which antagonizes everything that a human desires and makes it an evil to just be a human being. For me, the girls sometimes seem like a litter of kittens just aspiring for tenderness, for fun, for interaction, for freedom. My nine-month-old baby aspires for the same things. It’s just in human nature.”

Mustang is out now.

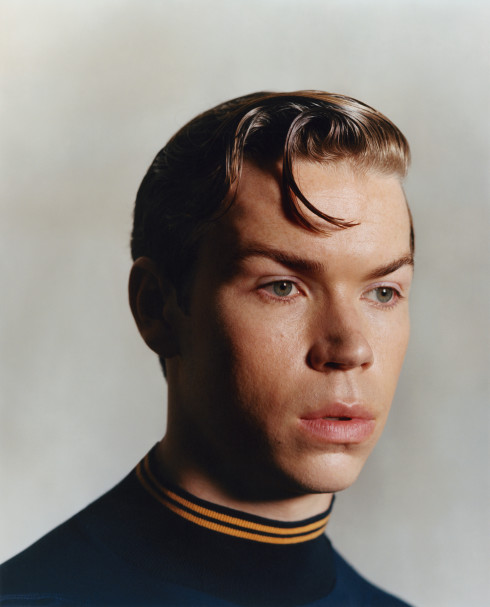

- By

- Jonathan Shia

- Photography by

- Adrian Gaut