- By

- Patrick Barrett

- Photography by

- Martin Lidell

Styling by Stefan Wiklund at Art Department. Photographer’s assistant: Mattias Satterstrom. Shot on location at Narcissa at The Standard, East Village, New York.

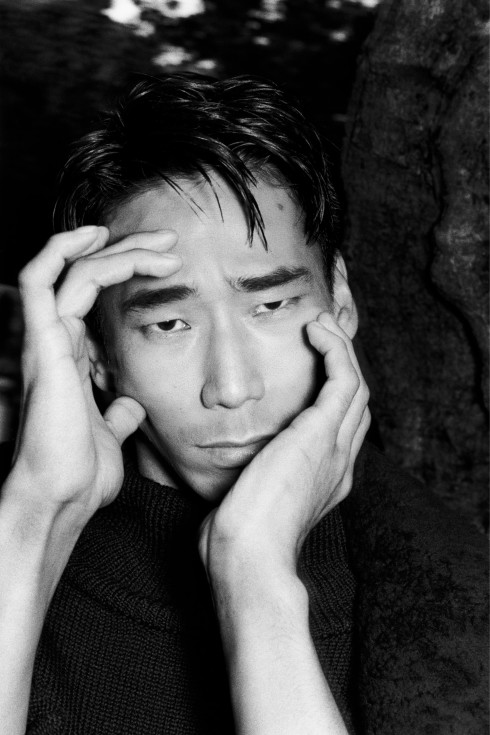

JOACHIM TRIER'S NEW FILM 'LOUDER THAN BOMBS'

When I sit down with Joachim Trier in The Standard, East Village’s restaurant, Narcissa, he has just barely finished with an early morning photo shoot. The coffee he ordered is still on the way, and a soggy, wind-bitten day has plastered itself to the restaurant’s glass ceilings, but when asked offhand if it’s strange to be photographed when he’s normally the one behind the camera, he lights up. It’s funny, he says. “As a director, I think you are sort of continually curious. Because what I do in any situation where I’m directing is try to figure out how people tick in terms of their creativity. So today, when someone takes my photo, I’m watching him and he’s watching me. I’m always learning from these things.” This curiosity is on full display in Trier’s newest film, Louder Than Bombs, which premiered at Cannes last year and is out in the United States today.

The Norwegian filmmaker’s first English-language film, Bombs follows a family in the suburbs of New York City struggling to keep itself together as publication nears of a controversial article about the mother’s work and suicide. On the surface a not-wholly-unusual family drama, the film is elevated by Trier’s unusually patient and precise eye, and an easy formal exuberance that renders the story unignorably compelling. Rather than rest on one clear protagonist, Bombs gives us glimpses us into the private moments of most of the major characters, which lends itself to a surprising and more subtly shaded portrait of family life than we’ve come to expect from the genre, and lets our understanding of the complicated dynamics between the family members shift and develop over the course of the film, almost without us realizing it. “Even in the closest of relationships,” says Trier, “there are still always little gaps, little unspoken truths that are difficult to convey for some reason or another. The story’s about trying to bridge that space.”

The subtlety of Trier’s storytelling, both here and in previous features like Reprise and Oslo, August 31, demands the sort of carefully tuned performances that are present here in spades. The film’s ensemble-based narrative functions beautifully in the hands of Gabriel Byrne, Isabelle Huppert, Jesse Eisenberg, and outstanding newcomer Devin Druid. In fact, says Trier, part of the draw of doing a film in America was being able to work with a strong cast of international actors. With the number of relationships the film explores, the set became a place where, from day to day, “there would always be new constellations of great actors” bouncing off each other in exciting ways. Huppert, in particular, mesmerizes as a war photographer torn between her cravings for home and for the world’s more overt war zones. Druid, without doubt the acting discovery of the film, turns in an arrestingly truthful performance as the awkward teenage son at constant odds with his father (played by Byrne).

But beyond its solid ensemble construction, Bombs derives much of its freshness from Trier’s playful formal approach. There’s a certain “humanist virtuous cinema,” as he calls it, that is all about transparency and pure, unfiltered observation. And that’s something he does extremely well, in this film and others (watch Oslo, August 31, if you haven’t). But he and longtime writing partner Eskil Vogt also introduce deliberate snags in the narrative thread, as when we enter the father’s thrill-baffled brain in the midst of his first real flirtation in years. In another memorable narrative jailbreak, a montage of material from YouTube, video games, science videos, and apparent home movies underlays a sprawling poetic confessional written by the youngest son. These sorts of interventions are taboo to the pure practitioner of cinema vérité. At the same time, though, the film’s patient observational realism feels foreign to the mainstream Hollywood mode. Trier’s unstaunchable curiosity makes his style orthodox to neither creed, and he wouldn’t have it any other way. When he was a kid, he explains, he discovered hip hop, and later was involved in the skating and punk music scene. “For me, that music, a new form created a new emotion,” he explains, “so when I talk about form, it’s not a remote thing, it’s not something to show off, to be pretty, or to alienate people. It’s actually to try to draw people in.” Formal elements that to others are a matter of dogma are, in Trier’s hands, simple tools like any other, and they are effective in Bombs exactly in so far as they are freely and unpretentiously employed. Talking about why voiceover and interior monologue felt so right to him in parts of this film, he describes how “in this pressure cooker of silence and secrecy, suddenly someone just speaks the truth straight to the audience and reveals themselves. I thought that dynamic of openness and closedness was truthful and sort of exciting.”

It is truthful, and the sharp attunement to daily life plus a willingness to be bold with storytelling techniques makes you excited to see what Trier will put his hand to next. “I love being in a cinema with people,” he says. “It’s one of the last contemplative spaces left in our society, where (at least still some) people turn off their cell phones and focus on something for a while. And I find that a beautiful place.”

Louder Than Bombs is out today in New York and Los Angeles.

- By

- Patrick Barrett

- Photography by

- Martin Lidell

Styling by Stefan Wiklund at Art Department. Photographer’s assistant: Mattias Satterstrom. Shot on location at Narcissa at The Standard, East Village, New York.