ALEXANDRE SINGH

“It is very easy for an artist to be cool,” says the multimedia Alexandre Singh. “The coolest thing you could do is wear sunglasses and sit in the lobby of the MoMA for a month and not say anything. Because you’ll look cool, and you’ll never say anything you regret. The same is true of [the current crop of] YouTube-ish art videos, where people are just talking nonstop: whatever it is they’re saying, they’re actually not saying anything, because they’re just making noise.” In opposition to this paper-thin coolness, Singh creates dialogue and rhetoric-driven performances and installations that climb inside culture and call it out on its laziness and disingenuousness, often at the expense of the artist’s own cool factor. “When you create a universe using dialogue, it feels like standing up naked in the gallery and saying, ‘I did this!’ Every word that you say lives and breathes out there, and reflects you. It is not cool.”

A Singh-crafted installation in this mold, titled The School for Objects Criticized, was included in the New Museum’s “Free” exhibition last fall. Composed of a group of vocally-animated household objects, (a neo-Marxist bleach bottle named Sergei, for example), the piece reminds one of a dialogue-driven radio play, while the conversation between the hilariously animistic objects centers on a take-down of what Singh views as the New York art world’s Hatfields and McCoys.

“In New York, one half of the art world believes in the artist as a wild child and a rebel, like a contemporary version of Basquiat. This artist is cool, he smokes cigarettes and is in touch with a primeval sensuality. He is deliberately anti-intellectual: a Sarah Palin of the art world, and he [embodies] a 19th-century idea of the artist: that he’s beyond language, almost primitive,” says Singh. “This is contrasted with the other half of the art world, which is very serious and reads a lot of Frankfurt School, and is very interested in the consequences of Marxism—their work deals with capital and labor. Both of these groups are talking about 19th-century concerns, and this is how New York operates: never getting beyond the antagonism between the two worlds, and [never realizing they could be more than one or the other].” The School for Objects Criticized is the artist’s witty retort, inviting artists and critics to stand up for something more authentic than juvenile disobedience or ideology.

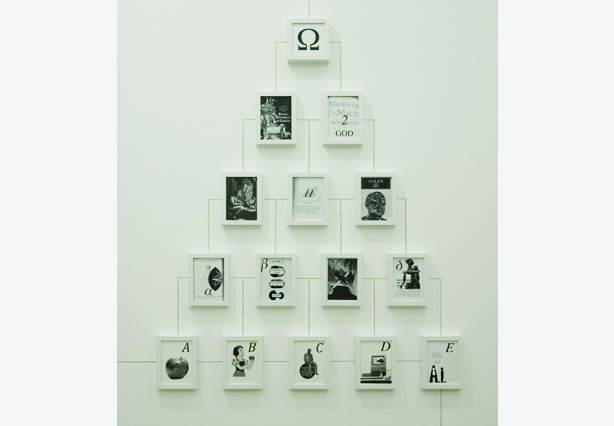

Singh is perhaps best known for his spoken performances, titled Assembly Instructions, where he lectures, tangentially, for more than three hours—nattily attired, stationed in front of an old-school overhead projector, illuminating images on a screen behind him. These pieces have also been reinterpreted into gallery installations of Byzantinely complex conglomerations of black-and-white images that visually narrate the interlocking thoughts of the artist. Black-and-white is a key aesthetic theme that travels through much of the artist’s work, and he views it as something of a branding tool: “I’m interested in creating work that’s seductive on the visual level, so it hopefully draws people in to spend a little bit of time with it.”

In connection to his sleek aesthetic, Singh’s thoughts and writings are tightly-honed treasures of pith and wisdom. Many of his ruminations return to what seems to be both a bête noire and a source of tremendous inspiration: 19th-century literature and theoretical motifs. One tangent (of so many) from the Assembly Instructions “is about the television programs Sex and the City and Grey’s Anatomy,” says Singh. “The protagonists of both shows, rather than being strong, modern women, are actually channeling the ideology of the 19th-century Romantic poets: that sort of dark, brooding person who doesn’t know what she wants, and rejects happiness.”

As it illuminates realities of contemporary culture that can go unexplored, Singh’s work is closely tied to literature. “[Prior to contemporary times] in a lot of the history of culture and art, people were able to talk about their context,” explains Singh. “I am a big fan of Diderot. He talked about things that were happening in Paris during his time and he took real people and put them into fictional works, which perhaps only happens now in South Park, which I adore.” To this point, Singh’s most ambitious work to date is a book, titled The Marque of the Third Stripe. The artist views the piece as “The first mature piece I did—it’s based on Adidas.” The Marque opens into a fictional gothic novella that recharacterizes Adidas founder Adolf Dassler as its meta-hero. It includes an invented synesthetic language, consisting of fluctuating patterns of pixels, meant to morph “concrete meaning into abstract, its equivalent,” says Singh.

This is a rather complex set of influences and agendas for art viewers to work through. Once inside Singh’s world, however, one navigates a totally unique universe architected by someone who is both in step with his time and able to transcend time; Singh’s thoughts often feel as though they belong to artists and writers from different centuries. It is this originality that has garnered Singh a great deal of success in the past few years, including a recent acquisition of his work by MoMA—of which, the artist says, “Suddenly all these edifices that seem very imposing when you’re outside of them become very normal when you step behind the curtain. The illusion is totally gone.”

Few younger artists experience this lucky turn of events, becoming, authentically, the thing they always longed to be. But one gets the feeling that Singh figured out his genuine self and craft quite a while ago—and now he’s simply inviting the rest of his contemporaries to follow suit.

Images courtesy of Harris Lieberman Gallery.