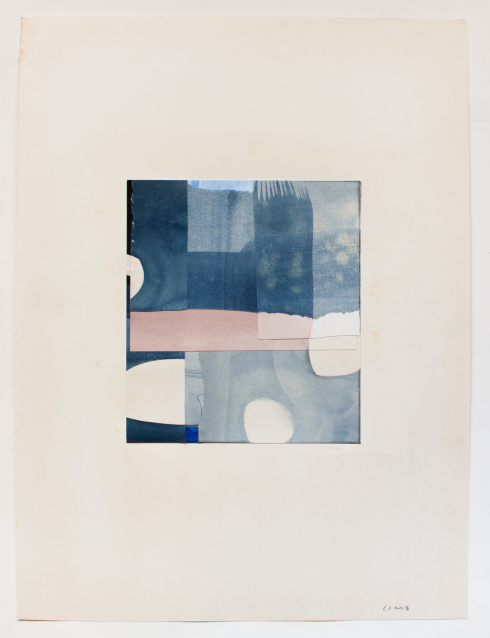

Field Experiments, Grounds for Play 001, 2015. Installation view, Moiety, Brooklyn. Photography by Max Dworkin.

- By

- Kevin Greenberg

All images courtesy of the artist.

BENJAMIN HARRISON BRYANT

On an early morning in late July, the mercury is already rising well into the eighties. In a Brooklyn architecture studio that occupies a sixth-floor space in a former paper factory, the artist and designer Benjamin Harrison Bryant is watching workers install air conditioning condensers on the hot asphalt tiles of a roof deck one floor below. One of the workers has sliced a side of the discarded cardboard packaging that held the condensers and cut a skull-shaped hole in it to create a makeshift, broad-brimmed sombrero to better shield himself from the heat and the glare of the sun. Bryant shakes his head in amazement. “Look at that,” he exclaims with a laugh. “Oh man, that’s genius.”

It’s no wonder he’s delighted: an unabashedly playful spirit of adaptive reuse and bricolage runs through Bryant’s work. A visit to his website immediately gives the lay of the land: an oblique (half-broken?) user interface creates a cheerfully off-kilter narrative that wobbles its way through examples of Bryant’s forays into the worlds of fine art, material research, and every stripe of design. In his work, mass-produced products artlessly mingle with handmade objects created by master artisans. Disposable promotional grocery posters are memorialized in stone with the same seriousness as a Greek bust. A storebought fishing net and a stone of very particular weight combine to create a counterbalance for a crude and colorful tropical chandelier. Everywhere the order of the day is surprise, thrift, and a humorous take on the post-consumer world. “I’ve definitely resisted trying to participate in the current polished culture of people who excel at a particular thing promoting themselves ruthlessly,” Bryant says. “That’s not how my mind works. I’m interested in too many mediums, and too many places.

“People always ask, ‘What do you make, though?’ Or ‘What material do you like?’ But it’s never been about that for me,” he continues. “It’s never been about a focus on one particular application or mastering, you know, cast resin, for example. I don’t really have one mode. It always comes back to ideas, to an ongoing conversation I’m having with the world. I often return to certain ad hoc principles.”

Bryant’s father owned a hardware store, and for the young designer, being surrounded by the purposeful flotsam of construction projects and home improvement left an indelible mark on the way he thought about art, design, and the world at large.

In the store, he recalls, “There were a million little bits and pieces that go together, and sometimes don’t necessarily go together. That was a huge influence on my creative process and thought. I found myself wondering, ‘OK, what are these industrial products that were brought into the world for a particular purpose, like some kind of gasket, or even a shovel?’ and trying to use those items as elements to illustrate a larger idea quickly and in an interesting way.”

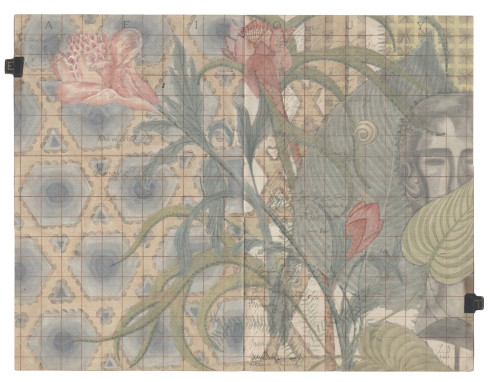

In addition to his solo practice, Bryant is also part of the design research trio Field Experiments, which began in 2009 as “a summer-long, transnational project undertaken in Bali, Indonesia, that explored the re-assemblage of cultural craft objects within a tourist-driven economy,” according to the introductory text of Indonesia, the collective’s inaugural catalog, published in 2014. Upon their return from Bali, Field Experiments created over fifty objects (or “souvenirs”) in close collaboration with local artisans “who work outside of the industrial system,” including “stonemasons, woodcarvers, batik-makers, kite designers, and painters.”

Bryant thinks again about the big cardboard hat he saw that morning. “There’s something there that I find almost infinitely powerful and witty,” he remarks. “Using the minimal resources of the objects you find around you and coming up with something really clever and useful, instead of entering that mindset of the world of high design: ‘Go ahead, you can make anything,’” he says, his hands outstretched to suggest an infinite cornucopia of the wondrous material possibilities that in 2016 we’ve come to take for granted: laser cutting, 3-D printing, injection molding, CNC, carbon fiber.

“Do we really need to bring more stuff into the world?” he asks, smiling and shaking his head.

“Travel is so important, you know,” he continues. “Getting out of the studio and seeking out moments like that homemade hat are critical for keeping an element of surprise and spontaneity in my practice. Otherwise it’s too easy to settle into a comfortable pattern of what works, instead of challenging yourself to interact with unfamiliar techniques and approaches to thinking about how the raw material—prefabricated or not—of a particular place can be employed and manipulated to various functional ends.”

Bryant plans to travel to Greece with Field Experiments this year to continue their outreach and research. “It’s a place we don’t know anything about,” he laughs. “It’s a black hole for us. We want to go somewhere where we can completely detach from comfortable processes or ways of working. That’s the research for us: entering a completely unknown location and emerging with real, on-the-ground experiences that we can draw from for a new body of work.”

- By

- Kevin Greenberg

All images courtesy of the artist.