HANS-PETER FELDMANN

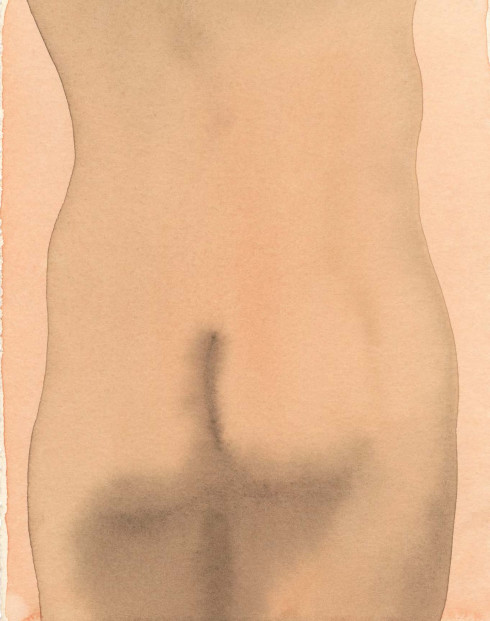

For Hans-Peter Feldmann, the unremarkable bits and fibers that make up the fabric of everyday life yield the most sublime art-making. Worn shoes, unmade beds, the act of washing a window—Feldmann presents the humble and unglorified for focused contemplation, in hopes that examining these objects anew will reveal something about the way we impart sentiment and meaning to the quotidian things that surround us.

Presentation is Feldmann’s forte. The seventy-year-old artist seems to prefer to think of himself as more of an art exhibitor or demonstrator, rather than an art-maker per se. He typically titles his shows simply “an exhibition of art,” underscoring the simplicity (and near banality) of the goings-on at the gallery. He stands emotionally apart from the works on display, preferring to allow contextual juxtapositions between works (and between work and viewer) to create a subtle but powerful meniscus of meaning.

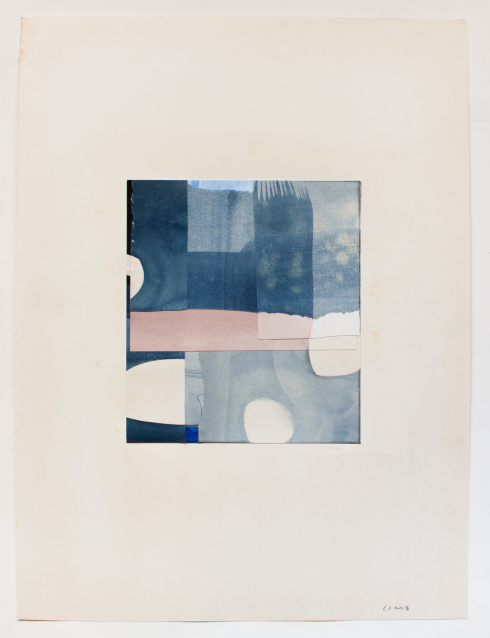

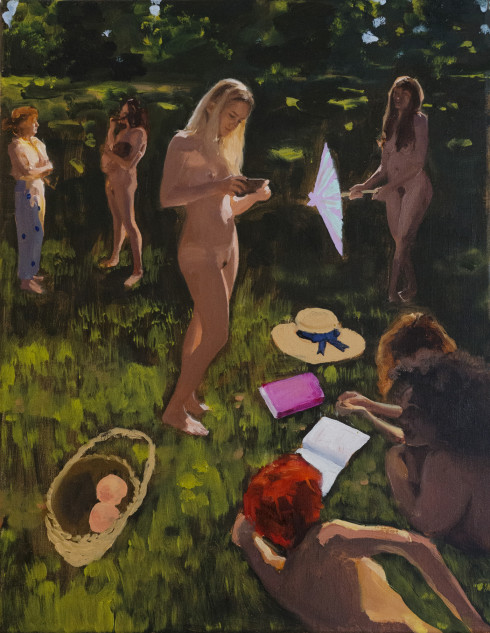

A new show at New York’s 303 Gallery demonstrates the artist’s range, but also the coherence and clarity of his project. For all its empirical distance, the thrust of Feldmann’s work cuts neatly across media. In the show at 303, the objects on display range from his trademark collages to sculptures to inkjet photo prints of caricatures of the artist made on the streets of Madrid.

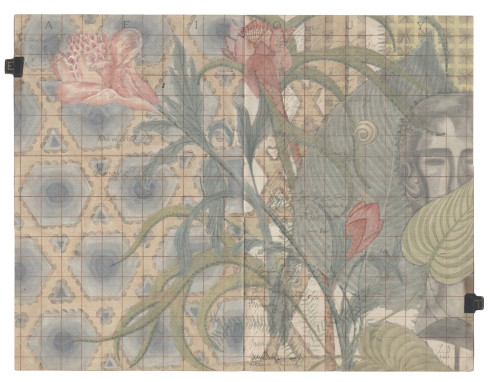

Feldmann, who is based in Düsseldorf (an appropriately modest urban setting), has been quietly, doggedly showing his art internationally for over forty years. Like his compatriot Gerhard Richter (who is Feldmann’s senior by only a few years), Feldmann grew up in a post-war landscape that was short on pictorial content. He has long been fascinated by snapshots and magazine clippings, and like Richter he has long maintained an extensive archive of secondhand images, ripe for recontextualization. But in place of the glamour and virtuosic technique that have made Richter’s paintings a perennial crowd-pleaser, Feldmann uses the borrowed images in his atlas to highlight hidden traces of life in objects that might otherwise go overlooked, and to demonstrate the inherent subjectivity of meaning and interpretation.

In a book-length interview with Hans-Ulrich Obrist, Feldmann chose to answer Obrist’s questions not with words, but with pictures, leaving the viewer to interpret just how the corresponding image that Feldmann selected responds to Obrist’s words. The results are whimsical, complex, and surprisingly potent, a deft participatory exercise in the relationship between language, vision, and meaning.

Feldmann’s approach to the presentation of actual objects can be even more striking. Last year Feldmann made waves when he was awarded the Guggenheim’s Hugo Boss Prize, an accolade usually reserved for much younger emerging artists that comes with a $100,000 check. For the accompanying exhibition, Feldmann chose to literally present the prize for examination, pinning one hundred thousand used one-dollar bills to the walls of the gallery. The visual texture (and surprisingly strong smell) of so many greenbacks in such a small space were enough to stop a viewer in his tracks. Literal? Yes. Simplistic? Of course. Powerful? Undeniably.

Perhaps in the current art climate, where spectacle and celebrity showboating have been the rule rather than the Warholian exception, there’s a growing place for the subtle charms of a septuagenarian from Düsseldorf who prefers to remind us that it’s the smallest, most humble things in our daily life that actually make the biggest impact.

“Hans-Peter Feldmann” runs through March 31 at 303 Gallery, 547 West 21st Street, New York. A separate solo exhibition will run April 11 through June 3 at the Serpentine Gallery, Kensington Gardens, London.

Images courtesy of 303 Gallery, New York.