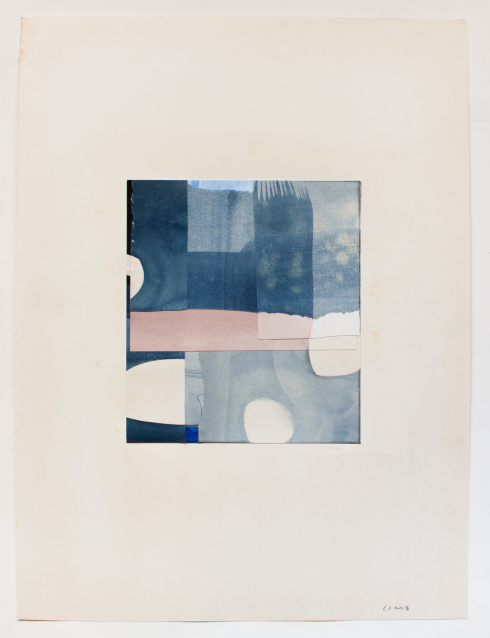

From left: Hilda Hellström, urn, “Sedimentations” series, 2015. Hilda Hellström, urn, “Sedimentations” series, 2014.

- By

- Gautam Balasundar

- Photography by

- Gustav Almestål

HILDA HELLSTRÖM

The camera pans across an elegant but eerily still room; furniture is covered in sheets, objects are scattered all over, dormant—relics of the past, perhaps. Barefoot men traverse a foggy, mountainous terrain, sifting through rocks, unearthing a stone unlike the rest. The distinct sediment formation is hoisted up like a trophy. Ambient tones oscillate as these images go by. Is it just a dream? Maybe it’s the future, too surreal to be the present. What’s certain is that the film brings to life Swedish artist Hilda Hellström’s unique stone-like creations, as a rare video interpretation of her work. Part of a piece titled The Monument, commissioned by Swarovski in 2012 for an exhibition at the London Design Museum, the film expresses an innate idea that’s a core part of Hellström’s striking artwork, as she elucidates: “People relate to objects with narratives. How can you imbue an object with a story to make people relate to it?”

Hellström grew up in Gothenburg, where her father was a carpenter who had a woodworking shop at their house in the countryside. It’s tempting to trace her proclivity for physical materials back to her youth building treehouses and the like, but it seems to have served more as a boundary that she had to transgress. “I was a bit bored with the fact that [wood] is a very restricting material,” she says. “There are certain ways that you’re supposed to join wood. If you work with traditional material, you already have context and all these associations that don’t actually have to do with the work.”

Instead, more visceral forces drew her to her career and her art form. “It’s just kind of basic, working with your hands,” she explains. “[It’s] like a longing that’s been there your whole life, and it’s a way to interpret life and reality through things you make three-dimensionally with your hands. It’s also such a pleasure; in the evening when you leave the studio, you can look at all these things you’ve done, and you can really see what you’ve made this day. It’s kind of satisfying.”

Hellström began to experiment with uncommon, malleable materials while getting her master’s degree at the Royal College of Art in London. During that time, she began her series of “Sedimentations,” urns cast from blocks of Jesmonite, a white resin invented only in 1984 that she manipulates with pigments to create layers of colors and fluid lines. “It’s interesting to work with a material where there are no real rules. Because it’s not a process that has been going on for thousands of years, so that gives you another type of freedom to work with it,” she asserts. “It creates some sort of wonder for people. They’d often wonder how and what my work is made of.”

The urns often yield associations with nature—waves, stars, and landscapes all seem to be depicted, but the effect is not intentional (in 2015, Hellström did in fact create a mountain sculpture commissioned by the Ace Hotel London). “Maybe it’s something subconscious. I grew up in the countryside so it might be,” she muses. “I have a strong connection to nature, and so in my work I always reinterpret it, in one way or another.” Undoubtedly, it’s connected to the concept behind her work; by appropriating something basic and natural like stone and creating something vibrant and conceptual, Hellström constructs a narrative around the object.

Her subsequent works have been more nuanced, but she has continued to find inspiration in the form of vessels, even if those shapes stray from the modernity the art world is so keen on. “Some of my research is focused on the basic idea of the vessel or the container,” she explains. “It’s such a beautiful object in many ways. If you go to an anthropological museum, part of the collection is made up of vessels from different cultures and eras. In many ways the vessel—to drink, eat, carry—is the original object. I’m continuously attempting to reinterpret the beauty of that original object.”

The shapes themselves become a part of the story she tells: “It’s about a subjective understanding of reality and how we appropriate reality ourselves, through our own minds—everything means different things to everybody. The material is an appropriation of a stone, and so the shape of the vessels is also an appropriation of a traditional or classical urn from an anthropological museum. So it’s about appropriation of reality in a way.”

Hellström has continued to find new ways to deploy her concept, recently completing a polyurethane sculpture that departs from her signature æsthetic style but retains the spirit of her work by resembling yet another material: ceramic. That’s led her to accept an invitation to explore the basics of actual ceramics, a much more traditional material than she’s usually inclined to use. But it’s merely a tool; her core ethos remains unwavering. “I was trained in design and we were asked to do these inane objects, and I’m like, Why am I supposed to do this? It doesn’t mean anything to anyone and we have so many products. How can I do something that means something to me and means something to someone else? So that’s always the intention: to keep working with these narratives.”

- By

- Gautam Balasundar

- Photography by

- Gustav Almestål