- By

- Zachary Sniderman

- Photography by

- Robert Lindholm

JONAH REIDER

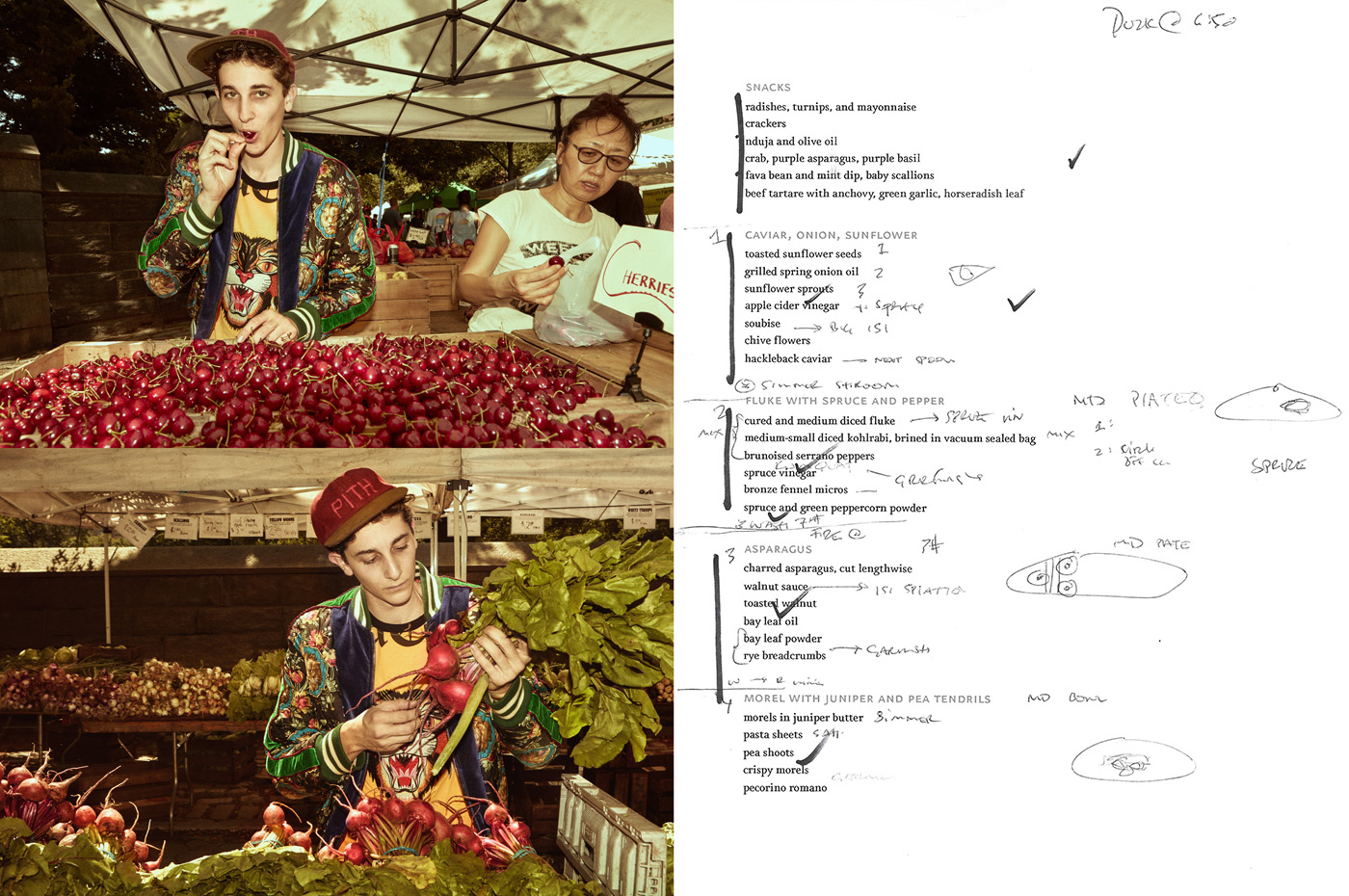

One bowl of perfectly stacked cherries, one bowl of just-stripped sugar snap peas, and a chilled French press of black tea dot the table at Jonah Reider’s home-slash-test kitchen-slash-exclusive dining club, Pith.

“Can I get you anything?” Reider asks, biting into a pea. “These are super in season right now.”

That sentiment—“Can I get you anything?”—is the kind of small gesture that is often extended out of formality, but for Reider, it means everything to his work.

Reider, twenty-three, cooks, but he does not consider himself a cook, or at least he does not refer to himself as “chef” when we gather at his sun-filled home wedged between the Navy Yards and Fort Greene in Brooklyn. The space is a bit of a godsend after his university, Columbia, kicked him out of his dorm room—the founding location of Pith. Reider crashed on couches and in music studios until a hedge fund manager proposed a solution—move in with him and his wife in their tony triplex and convert the main floor into the staging ground for his meals. Reider handles the supper club, and the three enjoy a profit share. But for the burgeoning chef, it’s the experience of each meal that’s most important, from the online booking to the passed apps all the way down to the vibe, dessert, music, ambiance, guests, and more.

Which is not to say Reider doesn’t care about the food. On his fridge—a silver French-door stacked like a mini walk-in with labeled mise en place and a bottle of Annie’s dressing from his roommates—he has a run list of that week’s menu, tweaked constantly to reflect what’s seasonal.

The dishes themselves are understated and structural—layering common-sense, complementary flavors in ways that are surprising and flecked with intelligent techniques and preparations. A dish, simply named “onion with sunflower and caviar,” is an interplay of textures and temperatures, hiding a rich onion base under a cloud of white. The idea of ephemerality has become a culinary calling card for Reider. “Cherry with wine and cardamom” carefully hides the rich reduction that acts as a base for the dessert. Oysters are served with a mignonette that highlights the bite of rhubarb and crunch of apple instead of diced shallot. The plates are elusive and considered, with surprises born from a deep knowledge of his available ingredients and the best techniques to apply to them. It’s a similar playfulness, grounded in respect, that has helped Daniel Humm and his flagship, Eleven Madison Park, to not only satisfy but also delight.

But you suspect Reider’s obsession with dishes is in service of the experience. “I didn’t want to be a ‘chef,’” Reider says, mulling over the word. “Some people want to be in a kitchen poring over plates, and there’s nothing wrong with that. But I want to consider all the parts of a meal. I want my guests to see me running around, I want them to see the pans, the plates, the smells.”

For Reider, meals have always been a social throughway, a meeting place for friends, family, or whoever’s nearby to literally break bread. “I remember going over to my friends’ houses when I was younger, and they would have this mandated dinnertime thing where everyone would sit around the table,” Reider says. “It was, ‘How was your day?’ ‘How was your day?’” That rigidity was “really odd” for him. Growing up in his own home, meals were melting pots of conversations and flavors.

That convivial chaos influenced Reider to experiment with foods from an early age. Early successes were met with equally happy accidents. “We were making this red wine reduction and the whole thing caught fire,” Reider remembers. “There were flames to the roof, like a real plume kind of deal.” From a young age, parties were opportunities for Reider to grow, cooking for friends and pairing an improving culinary talent with social experiences.

At Columbia, Reider, who initially meant to study jazz piano, picked up the moniker “dorm-room chef” for the high-taste, low-key supper parties he hosted in his shared dorm room. An innocuous review in the Columbia Spectator helped pique the curiosity of industry names like Ruth Reichl, whose interest in Reider’s novelty quickly turned into respect for his potential—and his approach. The New York Times mingled with his classmates, and DJs mixed with grad students. Unimpressed with a supper club on campus, however, Columbia evicted Reider, which led him down the path to his current home. In between Columbia and Pith as it exists now, Reider worked at Intro in Chicago and undertook a tour of Australia and New Zealand with the support of KitchenAid. Social virality—combined with the novelty of Reider’s approach and the circumstances of his eviction—generated the buzz, but his focus and ability are what earned him credibility.

Because Reider is young and has not spent years paying his dues in the trenches of a standard restaurant setup, it would be easy to brush him off as lucky, green, or, worse yet, blasé. But Reider is dedicated to his craft—one that includes both front-of-house and traditional back-of-house duties. “The thing is, this is not the best food you can get in New York,” Reider admits. “Straight up. But I guarantee you will have a great meal. I guarantee that.”

Reider pauses. This isn’t a slight on his cooking, but a realization that on a plate-to-plate match up, Pith—for all its care and attention—is not a Le Bernardin or a Gramercy Tavern. Reider understands his food is still improving, regardless of the current crop of great reviews. While he works on each of his plates, his market advantage is the experience of Pith, which is unlike so many other restaurants because it is so definitively not a restaurant. It’s not a supper club so much as it’s Reider’s home—each night is less a service and more a dinner party that goes just right.

It’s a complicated dance for Reider, who has to keep the front of house in view—greeting his guests, stoking conversation—at the same time that he’s fixated on the kitchen and all the cookery—the searing, layering, plating— one expects from a high-end dining experience.

But that tightrope is the one Reider is increasingly more confident, and more interested, in walking. Pith is pleasantly disorienting—Are you joining Reider at his home? Is he catering your night?—poking holes in the ideas of what an ideal restaurant, and a perfect meal, should be.

For more information, please visit Pith.space.

- By

- Zachary Sniderman

- Photography by

- Robert Lindholm