- By

- Zachary Sniderman

- Photography by

- Dan Martensen

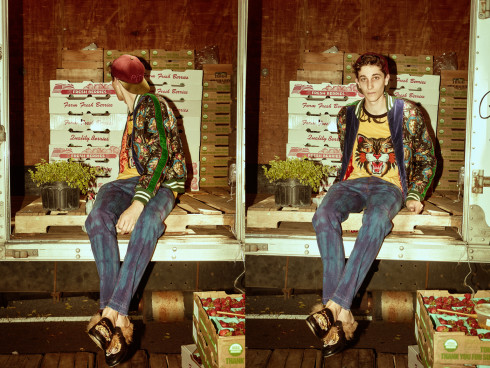

NEGRO PIATTONI

Most great restaurants strive to be ducks on the water: controlled and calm to the customer while harboring a throng of activity just under the surface. There are plates that need plating, orders that need picking up, refires and substitutions, missing ingredients and improvisation, dropped knives, nicks, burns, and the small victories when everything works as it should.

It would seem that the wildly unpredictable nature of a kitchen built around an open flame grill and a layout that puts the chef within arm’s reach and earshot of the dining room would be tantamount to a magician giving away his tricks. But to Norberto (Negro) Piattoni, the Argentine chef who opened his first restaurant, Metta, yesterday on a nearly perfect corner in Fort Greene, the beauty of his concept is about appreciating every piece of the process.

“The idea of the restaurant is not to waste anything,” Piattoni says. “You have to be respectful to the ingredients and to the people that are doing the work. Somebody was taking care of your lettuce or your chicken for days or months, they harvested it and put it on a truck, the truck brought it to someone else who brings it to you, and then you only use half and the rest you throw away? If you look at the process, you’d say, ‘Holy shit.’ It’s not that you just wasted what you’re not using, but you’re throwing away time and effort.”

Much has been made about Piattoni’s cooking technique, using an open flame (no gas or electricity) to cook a huge portion of the menu. The flame is where Piattoni will be stationed, firing and directing his kitchen. There is a common misconception that cooking over an open flame grill is, more or less, a fancy barbecue, but Piattoni is exploring the nuances of cooking techniques and how to apply them to delicate products and seasonal vegetables. “I am training everyone how to manipulate, how to work with an open fire,” he explains. “The menu will depend on how the ingredients react. We have all the ideas and we’re going to be doing a lot of interesting things with the fire and with the ashes and with the coals, all different techniques. We’ve also been preserving a lot of vegetables, drying, brines. We believe it’s pretty healthy for you.”

Locality and a light touch have been and will be hallmarks of Piattoni’s menus. “We’re trying to make a whole statement where people can believe it’s a nourishing restaurant,” Piattoni says. “People think there will be a lot of meat, they’ll just think, Oh, it’s an Argentine steak house, but we’re trying to get far away from that. Myself, I’ve been eating more vegan food and grains. Obviously we’re going to have some cuts of beef, some chicken, fish, some seafood, sometimes lamb, sometimes goat, but it’s not going to be a full menu where you have everything all the time. I’ve been working a lot with vegetables and grains and local farmers markets from upstate.”

In a similar streak, Piattoni is forgoing products that need to be flown in to preserve a sense of terroir on his menu. “Fish aren’t meant to fly in a plane, you know?” Piattoni says. “Basically, you can get the best product from any part of the world, tomorrow, in New York. You can just ask for it and someone will bring it to you. But why would you when you can call somebody in Montauk and say, ‘What did you catch today?’ and use it tomorrow?”

Originally from Argentina, Piattoni spent time growing up at his father’s farm, tending to goats and crops. A physical and emotional closeness to produce helped him along the path to becoming a chef, honing his skills alongside Francis Mallmann, at San Francisco’s Bar Tartine, and at his own pop-up at Fitzcarraldo in Bushwick last summer, which functioned as a kind of test run for his new space.

For a chef with such a primal method and wild look, Piattoni holds a gentle approach to ingredients, supply, and experimentation. He obsesses over new menus, chef collaborations, and esoteric ingredients like a series of botanical tinctures and distillations, as well as a love for quality sourcing: “A lot of that stuff comes from the time I spent in San Francisco working at Bar Tartine, where I really learned what is seasonal and how important it is to eat well,” Piattoni says. “Those guys are amazing.”

With such an open kitchen, where Piattoni is front and center, that love—or lack thereof—will be self-evident. “If you’re in a bad mood, it’s obvious. It’s not fun for anyone, for the whole restaurant,” Piattoni says, laughing. “What is fun about not drinking anymore is my mood is very stable. It’s not like you wake up with a hangover and you are completely fucked and you don’t want to talk with anyone; you feel like fucking shit, and then you have to be sweaty and taking Advils while you’re cooking. I think I wake up with a good mood every day.”

The best meals are ones made with feeling. “Some restaurants are so structured that they lose a little bit of their soul,” Piattoni explains. “What is the best meal you remember in your life? Probably it’s your mom or your grandmother cooking pasta for you or something like that, because she was cooking with so much love for you. She wasn’t worried about getting a paycheck at the end of the week, or having a restaurant make a lot of money or win three Michelin stars. All of that is just one more step to losing what’s important.”

Piattoni’s goal, oddly enough, is not to skyrocket into a trendy place but to grow and evolve, appropriately, with the physical space and his community. Earlier this year, as we sat talking in Fort Greene Park, the restaurant was a dusty mess with buzzsaws and hanging pipes. Piattoni was straddling every piece of its development, sweating over the menu, the construction, the design, hiring, and how to explain his life’s work in the right way as the launch date burned ever sooner. “In the beginning, there’s so much work to do,” Piattoni says. “Basically I have my hours as eight AM in the morning to one AM at night every day. There is no schedule. I will wake up, open the restaurant, I will close the restaurant, go to sleep, and then come back and do it again. It’s exciting because you’re doing it for you.”

Metta is now open at 197 Adelphi Street, Brooklyn.

- By

- Zachary Sniderman

- Photography by

- Dan Martensen