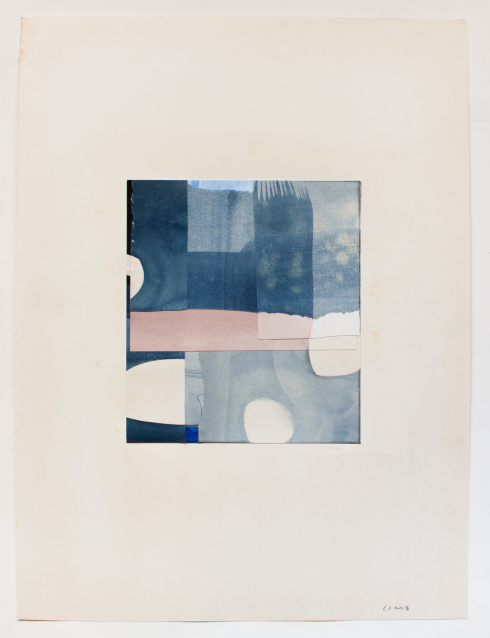

Lucas Blalock, Picture for Owen, 2011.

LUCAS BLALOCK

“Encountered obstacles are an invitation to get around them,” says the artist Lucas Blalock, giving voice to one of the dictums that guide his practice. His images, most of which are photographic compositions manipulated in Photoshop, are so casually and obviously altered as to have the appearance of slapdash, DIY collages. Blalock’s works possess a charming, unpretentious brio, a reflection of the artist’s preoccupation with process.

“I often think about photography as it relates to theater,” Blalock explains. “Early on, I became captivated by the films of Godard, and so I read as many interviews with him as I could.” Blalock noticed as he read that one figure who seemed to cast a long shadow over Godard’s processes and themes was Bertolt Brecht, the great German poet, playwright, theater director, and Marxist.

Early in his artistic career, Blalock began to incorporate Brechtian notions of alienation into his own photographic process. Although he is plainly consumed by the power of the photograph as a physical object in a space, Blalock is also perhaps equally interested in the way that the photographic image (and its physical artifact) separates the viewer from the object it depicts.

“My work is a product of the history of photography,” Blalock explains, alluding to the fact that, at best, photography is a “good copy” of the object it reproduces. Regardless of the quality of the reproduction, it’s still simply a facsimile that operates at a remove from reality, regardless of the amount of credulity with which the viewer might be ready to receive it.

Blalock’s interest in the candid realism of photography bleeds beyond objectivity into the endlessly subjective, seductive depths of digital retouching, the “goopy processes” that emerge out of Photoshop. It is at the intersection of those two worlds where he forges his practice, although Blalock insists that at heart he “feels like a photographer.”

It wasn’t necessarily the path he intended for himself. Originally Blalock was interested in writing for film. He says he has long been interested in cinema, especially its mechanics and its relation to the Theatre of the Absurd. “Being a fine-art photographer was about as far off the radar as you could get in terms of what I wanted to do with my life,” he laughs.

But Blalock embraces a multimedia approach to image-making. Though he creates with a camera (along with all of today’s seemingly requisite digital accompaniments), Blalock views photography as a form of drawing more than anything else. “Like drawing, it’s a way of understanding, of bringing something closer,” he says. “It always has been.”

Blalock has exhibited widely in group shows and has published a book, Towards a Warm Math, with the influential small press Hassla, full of images that run the gamut from prosaic domestic compositions to almost classically Surrealist still lifes to the kind of plainly manipulated tableaux that have captivated a recent generation of young artists. But a solo show in 2012 at Ramiken Crucible on New York’s Lower East Side afforded Blalock an opportunity to take his work in a new directionvz and to indulge his sincere, but untested, interest in space and spatial design.

“The architectural element of that show was probably the most gratifying element for me,” Blalock says, noting that the results resonated with him. He had managed to create “a perfect room, which revealed its flaws only from the outside.”

That tantalizingly delicate balance between slick perfection and obvious artifice, the close juxtaposition of elements that convince the viewer one moment and then shock her into critical objectivity the next, is one of the most beguiling traits in Blalock’s work. It’s an element that begins at the moment of artistic conception. “I’m constantly trying to surprise myself, to knock myself off-balance,” he says.

Like the rough edges of the spatial constructions that Blalock erected at his Ramiken Crucible show, ultimately it’s all about the framework. “Yes, you can think about photography as a good copy,” he says, “because at best, that’s what it is. But what happens when photography acts as a bad copy? That’s maybe a more interesting question to explore.”

For more information, please visit LucasBlalock.com. All images courtesy of the artist and Ramiken Crucible, New York.

Kevin Greenberg is the art editor of The Last Magazine. He is also a practicing architect and the principal of Space Exploration, an integrated architecture and interior design firm located in New York. In addition to his work for The Last Magazine, Kevin is an editor of PIN-UP, a semi-annual “magazine for architectural entertainment.”