MARTINO GAMPER

Many are the cautionary tales of domestic over-design that exist in popular culture, often employed to comic effect. Consider just a few examples from cinema: the pushbutton convenience-turned-slapstick disaster of the futuristic kitchen in Woody Allen’s Sleeper; the cold PoMo pretension of the city slickers in Beetlejuice (who populate the ghostly protagonists’ former Vermont Colonial with Memphis-inspired monstrosities while simultaneously giving the house itself a Peter Eisenman-ish overhaul); or the bumbling turn taken around an immaculately modern interior by the titular uncle of Jacques Tati’s Mon Oncle. The laughs are meant to drown out the real message, but they often don’t. Beneath the surface is a precautionary tale about the perils of elevating design beyond its rightful station.

It’s no accident that Martino Gamper chose to screen Tati’s film as part of “Design Is a State of Mind,” the show he curated that is currently on display at London’s Serpentine Sackler Gallery. Gamper, born in the South Tyrolean town of Merano in 1971, is a playful polymath whose work eludes easy categorization and often stands distinctly apart from conventional notions of “good design.” A graduate of the Royal College of Art, Gamper has remained in London since his graduation in 2000, and in those fourteen years has developed a unique, interdisciplinary practice.

For his 2007 project “100 Chairs in 100 Days,” Gamper employed salvaged scraps of discarded and abused furniture from London streets to create a chair a day. The results of the project are full of awkward, improvisational charm, each one a unique take on Gamper’s core philosophy that design should be the stuff of everyday life, not just the museum or the auction house.

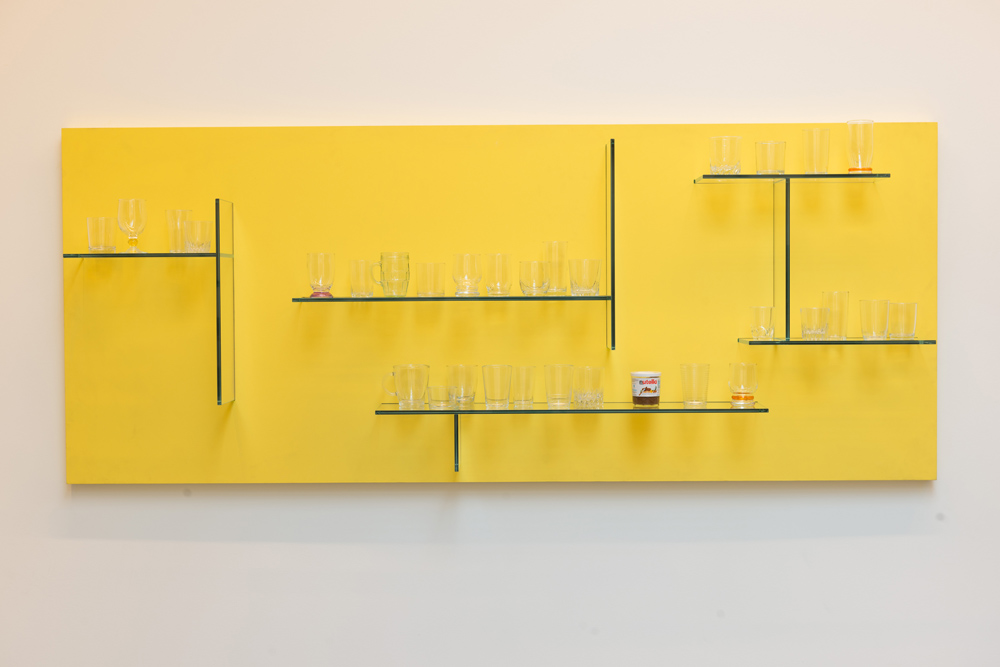

The eclecticism of Gamper’s vision is everywhere on display in “Design Is a State of Mind,” for which the artist invited friends and colleagues to populate various shelving systems—from a humble classic by Dexion to iconic designs by Ettore Sottsass, Andrea Branzi, and Gio Ponti—with collections of objects related to a theme of their choice.

Some of those choices are surprising: the designer Michael Anastassiades, best known for his elegant lighting designs, chose to display his collection of stones rounded smooth by rivers and oceans. Maki Suzuki presents an array of bricks and other masonry building units. Tony Dunne and Fiona Raby’s collection includes one pair each of men’s and women’s underwear, alongside various walkie talkies and transmitter devices. Max Lamb and Gemma Holt chose to present their collection of vessels by the renowned British potter Bernard Leach. In a separate room under glass vitrines, Gamper has laid a collection of paperweights owned by the great Enzo Mari.

The eclecticism of the show is surprisingly delightful, and underscores the themes that unify the diverse collections on display; namely, that good design can extend to the simplest, most functional objects of everyday life, and that the objects that surround us can and should be beautiful, ingenious things, no matter how humble their function. There are other ideas at work too, of course: notions of typology and iterative process loom large over many of the collections. The show is also a celebration of the simple pleasure of collecting itself, which always carries a whiff of obsession, no matter the collector’s chosen tchotchke.

To further emphasize the ideas that underpin his Serpentine show, Gamper staged a parallel project in conjunction with the storied Milanese department store La Rinascente during Milan’s Salone del Mobile earlier this year. That exhibition, entitled “In a State of Repair” invited visitors to bring an object to be fixed for free by a rotating roster of invited craftspeople. Part criticism of the disposability of many consumer objects, part celebration of the tradition of Italian craftsmanship, “In a State of Repair” echoed the simple joy of everyday objects that suffuses “Design Is a State of Mind.”

If these recent shows make anything clear, it’s that the social and interpersonal aspects of design are dear to Gamper’s heart. “Good design for me is when there’s a functionality that’s then challenged,” he has said. “[It] should combine function, materiality, form, and I think it should also respond to behavior a little bit: what this object does in a social context, how it changes our behavior, or how it helps our behavior.”

“Design Is a State of Mind” runs through Sunday at the Serpentine Sackler Gallery, Kensington Gardens, London. Photography by Hugo Glendinning. All images courtesy of the artists and Nilufar Gallery, Milan.

Kevin Greenberg is the art editor of The Last Magazine. He is also a practicing architect and the principal of Space Exploration, an integrated architecture and interior design firm located in New York. In addition to his work for The Last Magazine, Kevin is an editor of PIN-UP, a semi-annual “magazine for architectural entertainment.”