MICHAËL BORREMANS' LUSH PAINTINGS

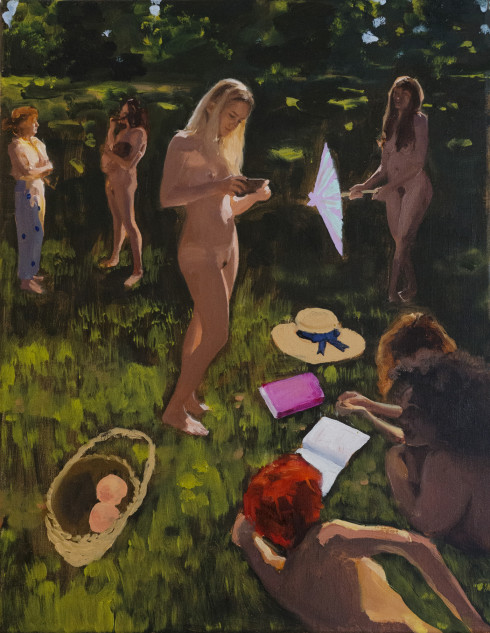

Lush and mysterious, Michaël Borremans’ canvases give the impression of emanations from a hidden, half-lit realm, operating wholly outside of our manicured reality. Rendered perhaps most uncanny by their eerie stillness, his paintings are populated with figures who act out odd pantomimes, alone or with each other, while seemingly in the depths of a somnambulant trance.

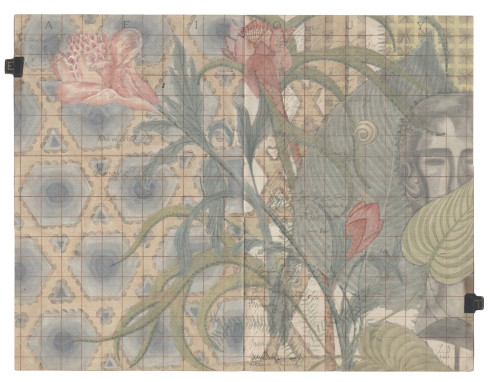

“This is fundamental: I don’t believe in painting nature. It’s been done,” says Borremans. “Nature is available to us, we don’t need painting for that. Instead, I try to depict culture.

“Since my childhood, I’ve lived in a world where everything is seen secondhand, on television and in the newspaper,” Borremans continues. “Even the world that is very close, you rarely see it first- hand. I always mistrusted those impressions.”

Trained in etching, Borremans has been painting since the mid-Nineties, operating with a blithe disregard for stylistic trends, crafting images in the same timeless figurative tradition as Manet, Velázquez, and Goya. Like those artists, Borremans’ paintings tap into something difficult to articulate—an elusive, universal truth about the human condition.

“These cultural references are slippery or implicit, but they’re there,” Borremans says. “Familiar, everyday elements and situations tend to find their way into my work, and yet the meaning remains elusive, even to me! There’s something odd in the way light or colors are used, or the technique. In each instance, there’s a dialogue with things we know already.

“It’s attractive to me because the resulting image inhabits an unclear place, and I like things to evade easy definition,” he continues. “If something is undefined, it’s a question that cannot be answered, and if you’re a viewer, you’re never finished with it. It lingers on in your mind.”

“Maybe this is my way of being an anarchist,” he laughs.

“It’s in my character. You hear all this stuff, ‘Oh it’s mysterious, it’s uncanny.’ That’s not my intention. Rather, it’s a refusal to use the image for what it’s intended for. At heart, I’m a romantic artist.”

Disorientation of a peculiar, particularly existential stripe is Borremans’ metier, and it’s built into the way he crafts his images. He begins with a photograph, but he’s careful to erase all traces of the photographic process from his compositions. He avoids using lenses with a focal length that diverges too much from the natural parameters of human vision. He’s adamant that his compositions appear to have been conceived as paintings, not photographs, even if photography is in fact their point of origin. He uses photographs “like sketches,” he explains.

“I take photographs in a very painterly way,” Borremans says. “My use of the medium is very backward. Taken by themselves, the photographs are not interesting. They’re only interesting if they get translated into paintings and engender a certain type of looking.”

The artist’s method is effective. The “certain type of looking” that Borremans’ paintings encourage yields an almost mystical, genuinely unnerving psychological effect. The deep, subaquatic torpor in which his subjects seem to reside—gazes hooded, hands outstretched in odd gestures of unclear significance—suggests a wholesale suspension of time, or maybe even of life itself.

Borremans suggests that he’s attempting to tap into a universal artistic theme: intersubjectivity. In truth, his paintings are about human relationships, the way people treat, and mistreat, each other.

Borremans insists that in recent years, he’s attempted to let a few cracks of light, however subtle, slip into the near-impenetrable gloom of his work. When he began painting, he says, he couldn’t help but see the shadow play of life as absurd. Now, he sees things a little differently.

“I love deluding myself,” he laughs. “It’s a new hobby I have. When I was younger, I took things too seriously, but life is a joke, and the trick is not to take it seriously. Maybe it comes from getting older. I live dangerously now. I take care of myself, because life is no fun if your body won’t participate, but now I fly little planes, I ride motorcycles, I dare to do anything. Ten years ago I worried about life insurance, about retirement. Now I don’t really care. If I take my work too seriously, I have a problem. It’s important to have fun and have a sense of humor.”

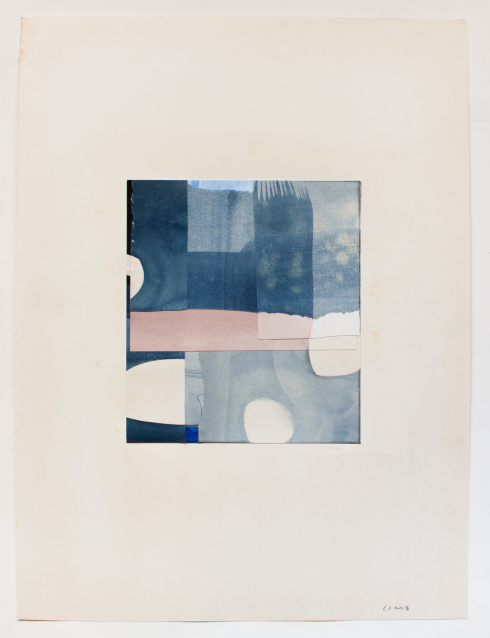

Borremans recently returned to etching after a nearly twenty-year hiatus. He has found that his time with a palette and brush has had a deep impact on the way he renders light in his etchings, and now he’s conceiving of an extremely small-scale, intimate show of drawings, to be held outside of the usual gallery or museum environment.

“It will take place in a small room, in a building with some program not related to art,” he says. “It could be a soundstage, a laboratory, a butcher shop, any kind of building.”

He would like the exhibit to travel, but not to the usual bustling capitals of the art market. At least one stop along the way should be extremely remote, a destination “for the real diehards,” he laughs.

Beyond the great Spanish masters, and beyond painting itself, another art form has exerted an inestimable influence on Borremans’ practice. Despite the silence and stillness that suffuse his paintings, and the waxen complexions and dead eyes of the shades who inhabit them, the stylized, exaggerated postures of Borremans’ subjects and the stark, shallow, chiaroscuro backdrops against which they are framed decidedly suggest another art form altogether: the theater.

“Michaël Borremans: As sweet as it gets” runs through July 5 at the Dallas Museum of Art, 1717 North Harwood, Dallas.

Kevin Greenberg is the art editor of The Last Magazine. He is also a practicing architect and the principal of Space Exploration, an integrated architecture and interior design firm located in New York. In addition to his work for The Last Magazine, Kevin is an editor of PIN-UP, a semi-annual “magazine for architectural entertainment.”