Photography by Stephanie Berger.

ORPHEUS UND EURYDIKE

There’s no shortage of action in London this summer, but one of the highlights of the season has been the Pina Bausch retrospective at Sadler’s Wells, a collection of ten of the globe-spanning choreographer’s works, each created after living in a different international city as part of a roving, swirling travelogue of sorts. The run met with an ecstatic response, one appropriate for a towering talent of her stature, and yet the glory of the performances was darkened by the thought that, after Bausch’s death in 2009, her Tanztheater Wuppertal company is headed for a definite, if yet-unscheduled, demise of its own.

New Yorkers had an opportunity to revist one of Bausch’s hallmark works this weekend as the Paris Opéra Ballet brought her Orpheus und Eurydike to the David H. Koch Theater as part of its two-week run during the Lincoln Center Festival. Bausch’s modern and poetic work, danced barefoot, might seem an odd choice for one of the world’s most storied classical ballet companies, but the piece—especially when viewed in contrast to the upright Giselle presented earlier in the week—was a perfect demonstration of the adventurousness the director of dance Brigitte Lefèvre has demonstrated since taking over in 1995.

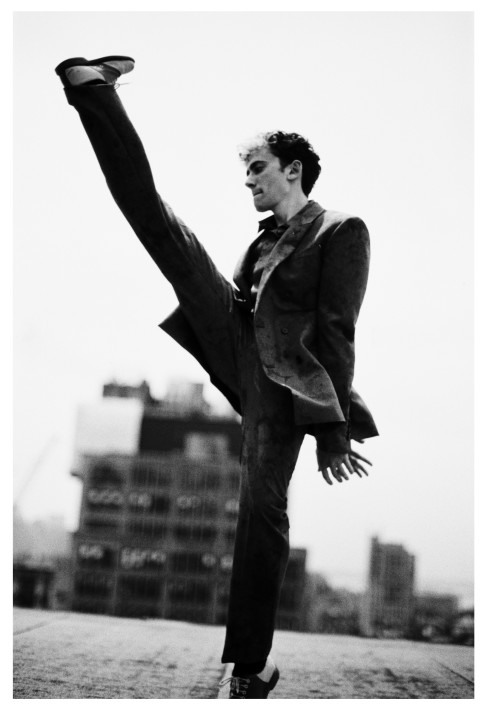

Orpheus und Eurydike, set to the Gluck opera of the same name (hear sung in a German translation), is a gloriously theatrical work, a coherent aesthetic statement from an artist then at the beginning of her decades-long career. The piece is broken into four parts—here titled “Mourning,” “Violence,” “Peace,” and “Death”—each with its own stunning mise-en-scène, from an enormous fallen tree reaching across the stage to a darkened antechamber strewn with armchairs. The main characters of Orpheus (here Love), Eurydike (Death), and Love (Youth) are each played by a paired singer and dancer, the former expressing Gluck’s gorgeous arias while the latter act out their various agonies.

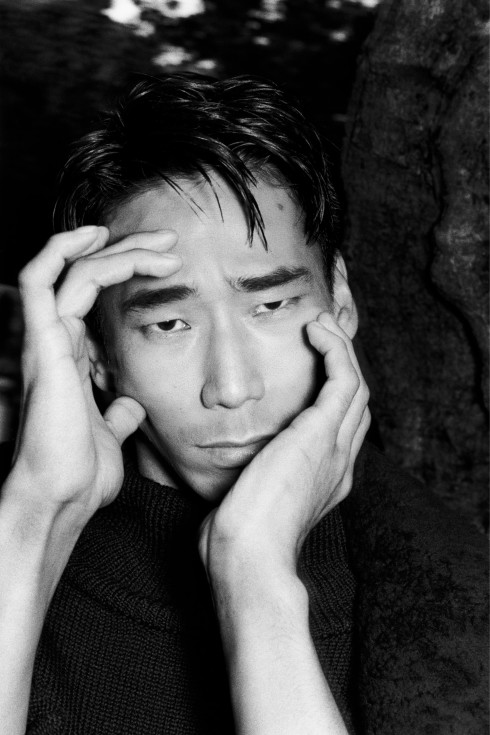

It is that grief that comes to the fore in this work, as the dancers grasp their heads in pain and contort themselves in Bausch’s emotive, evocative choreography. Over the course of the performance, certain gestures appear again and again, taking on a repetitive nature reminiscent of the monotonous mourning practices found in many ancient cultures. It’s a wonder to see how well these classically-trained dancers have taken to the extroverted and expressive movement, a world away from the strict lines and correct angles of their older repertory.

The original opera ends with the lovers reunited, a change from the original myth that Bausch here rejects, instead presenting us with the death of both. In the evening’s most striking moment, the supine body of the dancer Eurydike—here wrapped in a striking red dress—is laid across the stomach of her corresponding singer, and both lie there in quiet death for minutes as Orpheus laments his loss. It’s a stunning finale, overwhelming in its simplicity, and one that calls to mind the end of all things both great and small.

Photography by Stephanie Berger.