- By

- Kevin Greenberg

SAM BAKEWELL

In the current fine arts landscape, in which a newly rekindled interest in ceramics has led to dabbling legions of potters-come-lately professing their veneration for Bernard Leach as they turn out crude pinch pots by the dozen, the young British ceramics artist Sam Bakewell is the exception to the rule: a talented practitioner with the technical chops to traffic in realistic figuration, but an abiding interest in abstraction, totem, and ambiguity.

“For years now, probably since my undergraduate education, I’ve been making objects to help me when I get stuck,” says Bakewell. “Many of them were just tests, in a way: a glaze test, or a material study, or a study of an existing object I found fascinating for whatever reason. I made these small objects alongside whatever else I was creating at the time, but I never showed them. I held them back.

“In essence, these were just things I made to keep working in the face of not wanting to,” Bakewell laughs, “and then one day I realized they had begun to take on a life beyond that which I had intended for them. They began to take on the contours of a separate body of work.”

That body of work is at the heart of Imagination Dead Imagine, Bakewell’s first-prize-winning contribution to the 2015 British Ceramics Biennial’s AWARD exhibition, held in the China Hall of the old Spode Factory in Stoke-on-Trent. “The piece is named after a poem by Samuel Beckett, in which the suggestion is that by imagining the death of the imagination, it creates a new starting point from which to work,” Bakewell says.

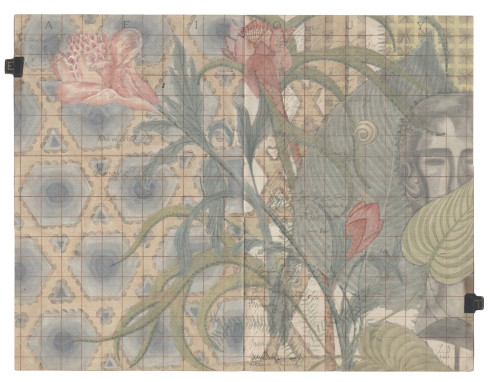

For Imagination Dead Imagine, Bakewell created a kind of primitive hut clad in pale clay, both its interior and exterior surfaces rendered with deep, textural whorls. Solid and weighty, its mystery is enhanced by the faded industrial texture of the room that serves as its backdrop. The structure’s intimate proportions and heady tactility imbue it, even from a distance, with an air of shamanism. It beckons like an architectural object from a deep, early morning dream.

The exterior of Imagination Dead Imagine is impressive enough, but once inside, the focus changes perceptibly, and volume decreases to a whisper. Inside the intimate confines of the roofless structure, examples of Bakewell’s work are displayed in small, irregularly shaped grottoes on each wall, each inviting close inspection behind a rectangular grid of fine wire. The featured objects vary considerably. The most beguiling teasingly straddle the line between figuration and abstraction, and, taken together, they create a mysterious and alluring private alphabet.

Each object’s nook stands at the center of a tight whorl of clay whose outer tendrils intermingle with those of its neighbors. These tidy maelstroms dovetail with another of Bakewell’s abiding interests: waves and curls, whose inherently unfixed and ever-changing contours are inextricable from the rustle of the phenomenal world—which itself exists within the ever-flowing river of time—and which have long fascinated sculptors. “I had been reading a lot of philosophy and semiotics about how curls and waves function mythologically as portals and beginnings and end points,” Bakewell notes.

The artist’s abiding interest in the meaning of these swirls is exemplified by one of the pieces showcased in Imagination Dead Imagine, a small mass of delicate ringlets entitled Of Beauty Reminiscing, which Bakewell fashioned from raw, un red clay and proceeded to carve into its final form, with a pin, over the course of two years. The process was extremely delicate, and at any time, the increasingly elaborate form was in danger of possibly catastrophic breakage.

Taken together, the pieces in Imagination Dead Imagine suggest a rare and intimate view into one artist’s private vocabulary. “I do want to just emphasize, though, that this collection of work is not meant to be religious,” Bakewell emphasizes. “Even though the pieces and their presentation might suggest Christian or Catholic iconography, and while I’m interested in those traditions, that’s not the whole story. There’s something in there about the interesting terrain between figuration and abstraction, and how fragments can become abstraction.

“There’s an interestingly ambiguous place where something figurative becomes fragmented, and even though it retains representational elements that are triggers for memory or that explicitly reference specific aspects of art history or the history of ceramics, just by fragmenting them, it creates a warp that renders the object abstract,” the artist emphasizes.

“I also think these pieces have helped me to come to terms with the fact that how I work is not, in fact, how others might work. It’s a much slower process, if it needs to be,” Bakewell continues.

In addition to his own practice, for the past three years Bakewell has assisted the ceramics artist Edmund de Waal, whose ethereal, approachable installations—essays in near-spiritual minimalism and seriality—have garnered widespread attention.

“In foundation, I really hated Minimalism, more in painting than anything, and now I feel like such a turncoat because working with Edmund has helped me to appreciate the language of Minimalism, and also the cross-pollination of art with architecture and poetry. It’s such a shame, because so few people really read poetry, and yet poetry is one of the last things that can really deeply affect you, or me at least,” he smiles.

- By

- Kevin Greenberg