Anton Alvarez, ‘The Thread Wrapping Machine Chair 111115,’ 2015.

- By

- Laura Bannister

- Photography by

- Gustav Almestål

ANTON ALVAREZ

In 2014, an unpublished chapter from Roald Dahl’s Charlie and the Chocolate Factory—initially declared too macabre for children—was released alongside squirmy, scratchy images from longtime Dahl collaborator Quentin Blake. In “The Vanilla Fudge Room,” Wonka’s golden-ticket winners visit an enormous confectionary mountain in the factory: five-stories, gooey, full of butter and sugar and milk. Workmen hack at the towering fudge mass with tools, sending colossal hunks rolling down to its base. These are picked up by cranes, deposited on identical wagons, and carried through a hole at the far end of the room.

After two children find themselves traveling through the same hole, Wonka tells their parents they are headed for the pounding and cutting room. “The rough fudge gets tipped out of the wagons, into the mouth of a huge machine,” Wonka says, coolly. “The machine then pounds it against the floor until it is all nice and smooth and thin. After that, a whole lot of knives come down and go chop chop chop, cutting it up into neat little squares, ready for the shops.”

Like his characters, Dahl was a great inventor—rigging Meccano machines between houses to drop water bombs, later co-creating a cerebral shunt to drain excess fluid from the brain. The machines in his books are spindly and complex and unconventionally strung together; they have levers and claws and clever, oddball elements. They are lean and effective, brought into being by a brilliant brain.

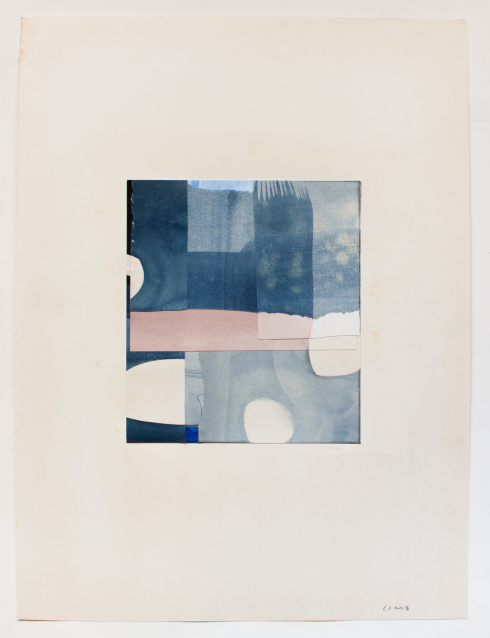

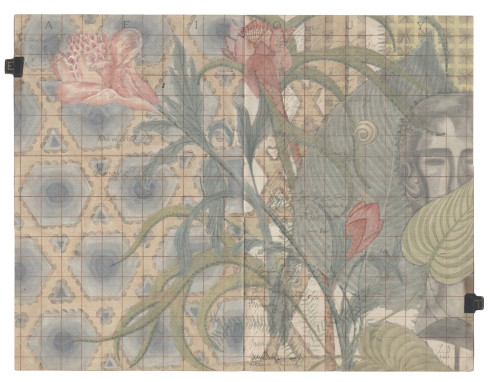

It is the same with Anton Alvarez. The Swedish-Chilean artist’s most seminal invention—the Thread Wrapping Machine—emerged a few years back and has been exhibited frequently since: at Art Basel Miami, at Salon 94, at London’s Gallery Libby Sellers, at Portugal’s Show Me Gallery. It is large and round and spins madly atop a set of legs, using glue-coated thread to join wood, steel and plastic without any screws or nails. The resulting objects (mainly furniture, and, more recently, abstract arches and pylons) are distinctly Dahl-esque, bound tightly by mad, frenzied strings of color, which function as a single, externalized joint. There are chairs with too many legs and perilously skinny lamps that splay into witchy, broom-like strands.

The Thread Wrapping Machine from Anton Alvarez on Vimeo.

Alvarez worked on the first version of this machine for a year. “I started doing very basic experiments, wrapping threads around stuff by hand, slowly [realizing] I needed a tool to do this,” he recalls. “I made the rst version, and maybe it was luck or skill, but it worked fine. I was very nervous with the second version, but it also worked ne. It took maybe a couple of weeks, a month, maybe a year, or even three, to get to the point where I’m starting to under- stand what’s possible with this technique.”

Alvarez owns two thread wrappers. They have been designed around his own operational needs. His shows and residencies—including one on view now at Taipei’s Xue Xue Institute—often integrate a performative element, allowing audiences to witness the process of thread fusing weighty materials. Sometimes they ask questions and sometimes they do not. One man remained transfixed for the duration of a stool’s construction. “He didn’t know anything about my project,” says Alvarez. “He knew about the gallery. He sat down on the floor and stayed there for three hours, watching.”

At the beginning of 2016, Alvarez’s schedule was harried—“working, eating, sleeping mostly.” During this interview, he was in Copenhagen judging a competition, while his assistant was in Stockholm, preparing and packing works for Taipei. From March to June, there’s a show at the National Centre for Craft and Design in Sleaford, England, where Alvarez will premiere a new invention—“a big clay extruder, a stainless steel tube filled with clay and a mechanical thing, pushing the clay out to different types of profiles, extruding shapes.” Staff at the museum will produce one object per day. Come May, Alvarez will have submitted a proposal to his former high school in north of Stockholm, which is being completely rebuilt and is integrating collaborations with artists and designers. “Getting in at this stage means you can have a nice discussion with the architects,” he explains. “The artwork or installation [proposed] can be very much part of the architecture.”

When Alvarez is not making or inventing, he listens to podcasts. One that stuck was a Planet Money episode on hoverboards—recent accessory of rappers and nauseating micro-celebrities—which have no singular logo, main distributor, or explicit origin narrative. “What’s interesting about that transportation device,” says Alvarez, excitedly, “is that there’s not one specific inventor. Most of the brands making them [typically copied other brands]. On this podcast, they dismantled one and found its components came from a big, rich city in China that builds a lot of our electrical products: computers, radios, telephones, whatever. They found this area within the city where all the factories sell components they’ve developed and share their concept drawings. There’s such a big demand—whatever they build—that these places aren’t afraid of anyone copying. They share ideas all the time. And that’s sort of how the hoverboard was born. I found it very interesting.”

“Anton Alvarez: How Long is a Piece of Thread?” runs through May 15 at the Xue Xue Institute, Taipei. “Anton Alvarez: Alphabet Aerobics” runs March 19 to June 5 at the National Centre for Craft & Design, Sleaford, England.

- By

- Laura Bannister

- Photography by

- Gustav Almestål