ARCHIE MOORE'S OLFACTORY ART

“When I said one memory was ‘pencils,’ he had his finger pointed to the ceiling with his eyes and said, ‘Aha! Cedar wood!’ and knew which compounds would achieve this.”

Archie Moore—an Aboriginal, multidisciplinary artist based in Queensland, Australia—is recounting his meetings with Jonathon Midgley of Damask Perfumery, a stranger-turned-collaborator and epicurean of smells. Moore describes Midgley as wizard-like in his olfactory observations, a man who could sniff one’s ‘stuff’ (concepts, memories) and translate them into something fantastically ephemeral: precise and complex aromas that climb up one’s nostrils and move around the brain, somewhere near the limbic system. As the two worked together, Midgley talked like a winemaker: he spoke of base and high notes and detected hints of cherry.

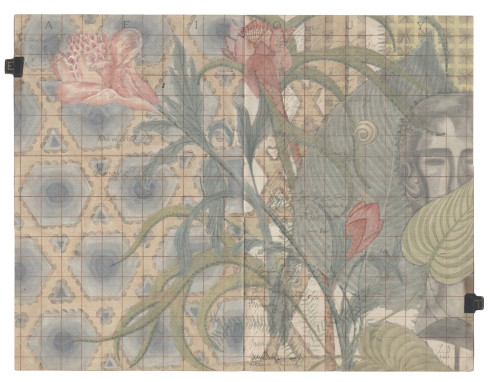

They say an artist is only as good as their last work (who exactly they are, I’ve never been sure). Moore’s last series, “Les Eaux d’Amoore,” is a selection of perfumes exhibited at the Commercial, a modestly sized—but ambitious—gallery in Sydney. In the dimly lit space, tall, clear bottles sat atop glowing shelves, accompanied by stacks of blotting cards—the kind dished out in department stores by women with clean hair and white teeth.

“Technically, they are all eau de toilettes because I didn’t need them to last on your skin,” says Moore. “I was only concerned with the immediate experience of smelling them. It was cheaper to make them this way also.”

Each of the seven smells in “Les Eaux d’Amoore” is a forceful glimpse into another’s memories, a sort of Rorschach test that references, as Bec Dean notes in the exhibition text, scent’s function as “a seat of prejudice.” Investiture smells like the artist’s first girlfriend. She wore rose oil and Elizabeth Arden’s Red Door. Presage is graphite pencils and paper, riddled with anxieties from the first day of school. Un Certain T’y has the odor of Moore’s father, weighty and earthy, reminiscent of clay and wood-fire smoke. Moore explains, “When I was very young he would take me with him to his earthmoving jobs, digging up the earth for dams. The perfume name is me having fun playing with words: uncertainty in the English sense, because I was always unsure if he was my biological father.”

Moore’s youth—marked by poverty, volatility, and the isolation of growing up as an Aboriginal child in a white-dominated environment—felt awkward set against these symbols of wealth and excess: fancy bottles housing perfume compounds, sterile shelving. The intention was to unsettle, of course, creating a deliberate tension between the physical work and Moore’s ideas.

The funny thing about memories is that they are fragile and unreliable, nearly always selective. We rarely remember things as they really occurred, glossing over bits, hyperbolizing. Moore is hyper-aware of this tendency to reconstruct, along with our inability to truly grasp the recollections of another. Much of his work is participatory in this way, initiating a dialogue concerning race and Aboriginal politics, integrating his lived experience and asking others to fill in the blanks. Good art, Moore knows, has a way of embedding itself in an audience, leaving some residue as the viewer walks away.

“I wanted it to be an audience sniffing my memories,” says Moore, “but how can they remember what I remember? Do I even have an accurate recollection of my own experience? I see all this as a bit of a metaphor for the failure of reconciliation. Can indigenous and non-indigenous ever really, fully understand or have empathy for each other?”

As an artist, Moore is easily bored, exploring various formal considerations (drawings, sculpture, videos, installation, photographs) until he pinpoints the one that will best convey an idea. For one self-portrait, a twisted, confrontational readymade, he covered a taxidermy Bull Terrier in shoe polish and attached a collar which read, “Archie.” For another piece, Clover, a tent-like structure propped up with sticks, he interrogated the cruelties of political ignorance and institutional racism. Currently, Moore is designing a flag for every nation of Queensland, based on an anthropological map dating to 1900. “There’s fourteen Aboriginal nations he identified,” Moore says of the map’s creator, “rather inaccurately, I would say, but he was one of the first to see Aboriginal Nationhood.”

Moore graduated from Queensland University of Technology in 1998, with a bachelor of visual arts. Three years later, he was awarded an international scholarship, enabling him to study at Prague’s Academy of Fine Arts. The experience merely extended his sense of psychological displacement to another locale: Moore often feels “like a bubble, floating on an ocean of acquaintances.” Still, he is no stranger to accolades: shortlisted six times for the Telstra National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Award, and the 2010 winner of the Woollahra Small Sculpture Prize.

Moore used to wear perfume (a synthetic rose oil) but it has long been discontinued. He now goes without one and receives no complaints on his natural scent.

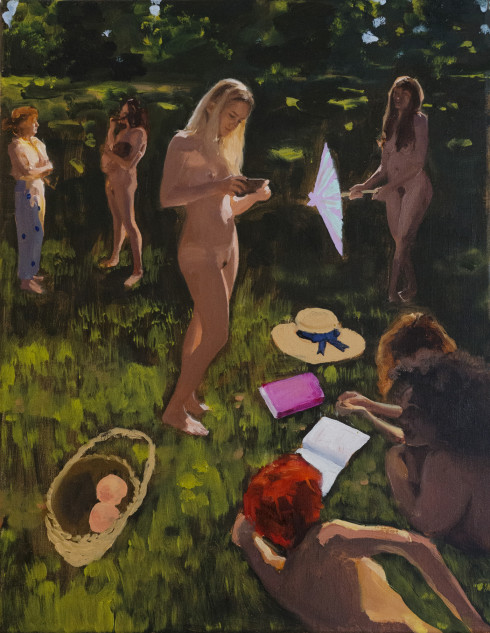

Photography by Jessica Maurer. Courtesy the artist and The Commercial Gallery, Sydney.

Laura Bannister is a writer currently based in Sydney, Australia, and the editor-in-chief of Museum magazine.