DAVID ARMSTRONG, 1954-2014

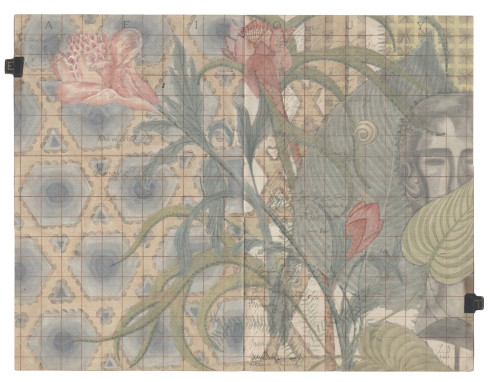

The ultimate goal of the portrait photographer’s art is intimacy: the ability to convey, through light and composition alone, a look into the subject’s soul. The photographer David Armstrong, who died in Los Angeles on October 26th after a battle with liver cancer, possessed a rare ability to imbue his portraits with an unusual subtlety and quiet dignity. The silence of his photographs spoke volumes about those upon whom he trained his lens.

Armstrong, who rose to prominence in the Seventies alongside his friends Nan Goldin, Mark Morrisroe, and Jack Pierson, never shied away from the fact that the success of his portraits was the result of a complex admixture of desire and seduction. Armstrong was technically gifted, but the strength of his compositions is not what makes his work so special: rather, it was Armstrong’s ability to put his subjects at ease, to dissolve the emotional barriers that so often exist when an individual is exposed to the unforgiving aperture of a serious camera (and often a host of other equipment, plus a retinue of assistants), and asked to “relax.” At their most haunting, Armstrong’s portraits reveal his subjects with their guard completely down, as if captured in some fleeting and silent moment of post-coital bliss.

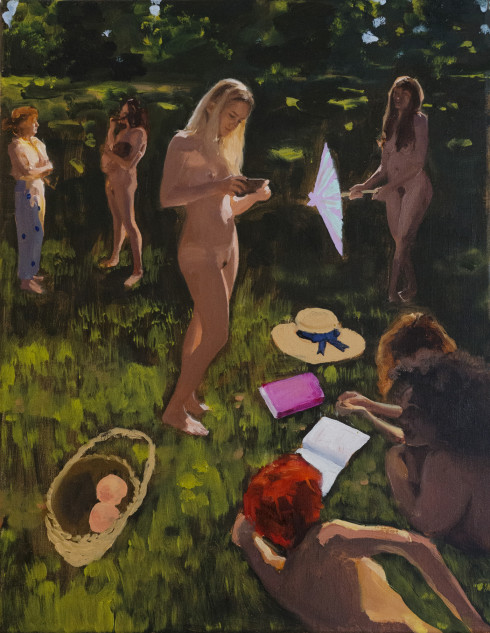

Openly gay, Armstrong moved to New York in 1981, and, shortly after, showed his photographs in MoMA PS1’s era-defining show “New York/New Wave.” By the Nineties, Armstrong had established himself as an important fashion photographer, and his editorials were regularly featured in many of the world’s most important fashion periodicals, but it was for his less commercial work that he was perhaps best loved. Armstrong’s portraits of attractive men exalting in the “bloom of youth” (which the photographer once famously calculated to last “about six months”), mostly shot in upstate New York or in his beloved Bedford-Stuyvesant row house in Brooklyn, remain his most potent works. In his personal work, Armstrong mostly photographed friends and lovers. By his own admission, he was drawn to men with a self-destructive side: his photographs are full of callboys, ruffians, and drifters worth of Genet. There is an inky darkness to much of Armstrong’s work, even at is most romantic, and the “beautiful boys” who inhabit many of his most famous compositions often exude an undeniable (and not unattractive) malice. That Armstrong was able to so gracefully inject tenderness into portraits of men whose personas often seem deliberately molded to reject or conceal their humanity was perhaps the surest evidence of his talent.

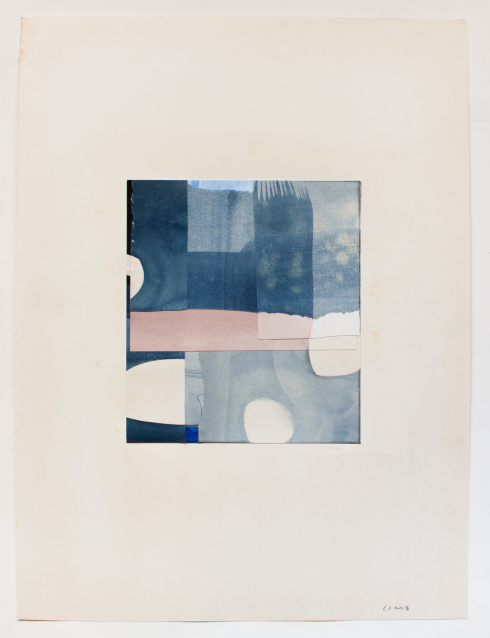

Later in life, Armstrong began to produce soft-focus landscapes, which stood in elegant counterpoint to the fine detail of his portraiture. Armstrong often showed the two styles side by side, creating haunting, indirect narratives that underscored the introspective sensibility that had long defined his work. It might seem nice to imagine that, toward the end of his life, Armstrong was able to banish some of his own demons and make peace with the world, but perhaps it was those demons, and that darkness, that made his tender, sexy, self-contradictory art possible in the first place.