MELISSA GAMWELL

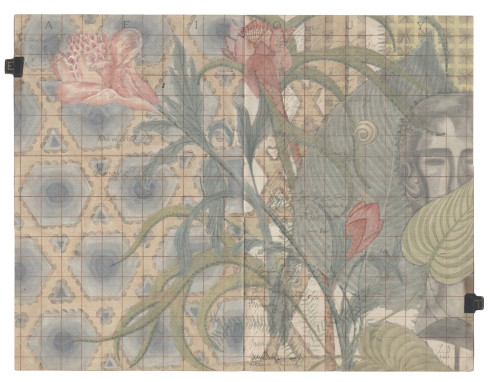

The gnarled and pocked contours of an unearthed animal bone, carefully catalogued shards of attic pottery, the viscosity of a new batch of bone-china slip or heated wax: these are the things that make the artist Melissa Gamwell’s heart beat a little faster. Gamwell uses a sophisticated technical process involving bone china, phosphate dyes, water, and semiprecious metals to create sculptural objects that seductively straddle the line between the fine and applied arts. The result is beautifully disconcerting: fine china and flatware firmly reimagined through the chaotic logic of the natural world.

“I’m obsessed with the idea of people using unusual-looking objects that are actually perfectly functional,” she says. “In general I’m not crazy about Salvador Dalí’s paintings, but a few of the forms in his popular canvases—the animals in Dream Caused by the Flight of a Bee Around a Pomegranate a Second Before Awakening, the clocks in The Persistence of Memory—really made an impression on me as a child.” Dalí’s breed of organic distortion appealed to Gamwell. “I imagine something similar, but in use,” she says. “A giant bowl embedded in a wall, for example, really allowing objects to have a new situation within a landscape.”

It’s hard not to see the echoes of Surrealism, with its grotesque fascination with the body and its processes, in Gamwell’s work. Rarely since Méret Oppenheim’s famously furry teacup have domestic objects felt so alien or so alive. But it’s Gamwell’s fastidious dedication to her craft that makes her work so truly compelling.

Gamwell graduated with a master’s degree from London’s Royal College of Art, famed for the rigor of its ceramics program, and it was there that she developed the processes she uses to create the pieces in her current body of work.

“I started playing by disrupting the casting process,” she explains. “After a while, I stepped back from my work and saw a collection of forms that looked like the results of some early culture slowly developing functional wares. It was instinctive for me to approach these as if they were artifacts of a process. There was one set of pieces, which are mostly destroyed now, which were so thin you could use them only once! The appeal for me was that I was able to develop a material that could cast that thinly and to craft a narrative for its use, even if it was an impractical one.”

Gamwell grew up in the woods of Maine in a late-nineteenth-century farmhouse. She credits her upbringing with her love of craft and her enduring interest in natural forms. While Gamwell cites those surroundings as a major inspiration, it’s the unpredictable mechanisms of nature that fascinate her most.

“I’m interested in combining certain processes and materials to yield a result that looks like it has the unpredictable genius of nature,” she says. “In the sense of true experimentation, I’m leaving the form up to the variables I’ve engineered, so in my own little capsule, it is as close to natural as it can be.”

Both in the way she creates and displays her creations, there is a scholarly, almost archaeological aspect to Gamwell’s practice. She is fascinated by the arrangement, composition, and cataloguing of objects, both natural and manmade.

“I’m really interested in culture’s interpretation of found artifacts,” she notes, “and how they are presented in museums. One of my favorite places is the Enlightenment Gallery in the British Museum, where the visitor gets a firsthand look at the changes in approach to the classification of natural and handmade objects from Darwin forward. How did people classify a mammoth skull in relation to the fruits of the Egyptian excavations? It feeds my obsession with catalogues.”

Gamwell’s most recent infatuation? Numbers from the voluminous back catalogue of The Athenian Agora, a hardbound scholarly journal that compiles all of the pottery fragments unearthed at the Agora by the American School of Classical Studies at Athens. “Accompanying each catalogue number is a descrip- tion of the figures on the pottery shard that is so technical that it transcends scholarship and crosses over into the realm of the heart-achingly poetic,” Gamwell says.

Recently, the uniquely seductive language of Gamwell’s work caught the attention of E.R. Butler, a high-end architectural hardware company. This autumn, the vitrines in the windows of the manufacturer’s appointment-only Prince Street showroom in New York will be given over to Gamwell to design and to populate with her work. For Gamwell, it’s a perfectly unconventional match.

“I want to show you these things as if they had been unearthed at the site of ruins, or stumbled upon protruding out of the dirt of a tropical forest floor and brought to a moody darkroom with the pallor of a Vermeer painting in order to be made sense of,” she smiles. “To make it even more æsthetically perfect, that room would also have the thickest stormy-gray stone slabwork table you’ve ever seen, surrounded by Breuer chairs and lots of dark rattan wall panels. The windows at Butler are not big enough for all of that, but I will show some examples of those organizations. I’m not opposed to the more standard structure of a gallery, but I have so many ideas about how this work is best experienced that the opportunity to engage more of that narrative is ideal.”

Melissa Gamwell’s “Functional Mythologies” is on view at E.R. Butler, 55 Prince Street, New York, through November 21. All images courtesy of the artist.

Kevin Greenberg is the art editor of The Last Magazine. He is also a practicing architect and the principal of Space Exploration, an integrated architecture and interior design firm located in New York. In addition to his work for The Last Magazine, Kevin is an editor of PIN-UP, a semi-annual “magazine for architectural entertainment.”