- By

- Yelena Perlin

- Photography by

- Hector Perez

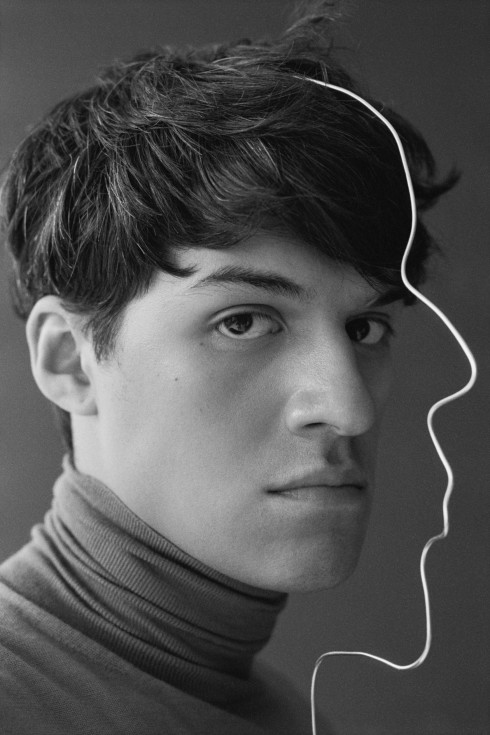

CÉCILE MCLORIN SALVANT

Everyone can name the reigning queens of jazz: Ella Fitzgerald, Billie Holiday, Sarah Vaughan. Their youthful, ignited energy, powerful voices, and vibrant spirits forever changed both jazz and popular music, yet over a century after jazz entered into the pop culture zeitgeist, you have to wonder, when will the torch finally get passed?

“[Jazz] has this youthful, fiery energy to it. I like that energy,” says Cécile McLorin Salvant over tea, in a moment of calm after a full day of press earlier this fall. In fact, the 26-year-old jazz virtuoso more than likes that energy—it is part of her being, and we witness it firsthand when she takes the stage for her two back-to-back, sold-out shows at Harlem’s Ginny’s Supper Club the following evening with support from pianist Adam Birnbaum, bassist Rufus Reid, and drummer Joe Farnsworth, all notably her senior. A storyteller in song and in speech, McLorin Salvant introduces every number she sings from her collection of standard jazz and songbook hits, actively avoiding songs she’s recorded and instead choosing to test out new material she might make her own. Opening with Ella Fitzgerald’s “The Gentleman Is a Dope” and continuing into several Cole Porter songs, including “Easy To Love” and “I Am in Love” (popularized by Billie Holiday and Ella Fitzgerald, respectively), she channels the iconic singers to whom she is often compared. Effortlessly playing with the variations of her pitch, McLorin Salvant shows off the wide range of her vocal timbre, bringing new life to “Brother, Can You Spare A Dime” in both a low contralto and a high soprano, singing, “Why, don’t you remember, I’m your pal/Say buddy, can you spare a dime.”

The Miami-born McLorin Salvant began studying classical voice at the age of five, and by eight was singing in the Miami Choral Society. The proud daughter of immigrants—her Guadeloupian mother is from France, while her father is Haitian—McLorin Salvant was immersed in all kinds of music from early age. “Any given day could be a different experience sonically at home,” she says. At eighteen, she moved to Aix-en-Provence in the south of France to attend university, choosing to study political science because it was “the first thing that came into my head.” While continuing her study of classical and Baroque voice, she met the reedist Jean-François Bonnel, who, as her teacher, guided McLorin Salvant’s growing interest in vocal jazz, introducing her to the early-Twentieth-century music she would soon embrace. “[He] really stressed the importance of knowing that music and of playing that music today,” she says.

In 2010, McLorin Salvant released her début album, Cecile, backed by the Jean-François Bonnel Paris Quintet, and in the same year went on to win the prestigious Thelonious Monk International Jazz Competition; the prize included a major-label recording contract. In an effort to move to New York, she decided to try out the “regular college experience,” attending the New School for a semester, quickly choosing to drop out and move back to Miami to record her major-label début, Womanchild for Mack Avenue Records, which would be nominated for the 2014 Grammy Award for Best Jazz Vocal Album. McLorin Salvant was twenty-three.

This September, McLorin Salvant released For One to Love, and, as much as the new album continues with the tradition of the jazz and pop standards she has become known for, the now 2016 Grammy-nominated For One to Love is different. It’s an effort of, well, love. “For One To Love is a lot more personal,” says McLorin Salvant. “Womanchild is a studio album, with a studio band that I put together, that I didn’t really know if they could sound good together.” (They do.) “For One To Love is with my band that I’ve been singing with for two-and-a-half years. They’re really close friends of mine,” she warmly reflects.

“I wonder if he even knows my name/My name between those lips or on that tongue/Would make me lose what ground I’m on,” sings McLorin Salvant on the deeply personal “Left Over,” about an unrequited love, one of the five she wrote on For One To Love. The naturally shy McLorin Salvant spoke candidly about her recording process for laying down the track. “I had to kind of get drunk to record it,” she recounts. “I had two or three shots of whiskey. I went into the studio and I was sitting at the piano and I was like, ‘Don’t record. This is just a test.’ And then when I was finished, I was like, ‘Did you record that?’” says McLorin Salvant, adding, “I was like, ‘I can’t do it anymore!’”

McLorin Salvant doesn’t, however, put too much pressure on herself to write songs, instead bringing new energy to those she chooses to perform. “I’ve listened to so many of these great singers,” she says, citing Judy Garland as an example. “They just did a great job singing.” She adds, “It’s two totally different skill sets. The whole singer/songwriter thing can be a huge trap.” The rare, often neglected deep-cut songs she selects have become one of her signatures. “I really wanted to know if there’s a history of feminist songs in jazz, and that’s really hard to find,” reveals McLorin Salvant. “The opposite is very easy to find, so I started collecting those.” One of those songs is on For One To Love—McLorin Salvant sings Burt Bacharach and Hal David’s “Wives and Lovers,” an almost unintentionally chauvinistic hit from 1963 that advised wives to be good to their husbands (lest they find a younger piece elsewhere), which, performed in 2015, makes the listener wonder if anything has even changed. Her version of Valaida Snow’s immensely racist 1934 song “You Bring Out the Savage in Me” on Womanchild is equally transformative and absurdist. “I was like, ‘This is crazy, I need to sing it!’” gleefully explains McLorin Salvant. “Listen, I like to laugh. I like to just make fun of these things,” she says. “There is just a really interesting history behind it of appropriation and reappropriation.”

Fittingly, McLorin Salvant’s comedic timing is impeccable. At Ginny’s, as she introduces Blossom Dearie’s “The Ballad of the Shape of Things,” she transports the audience to “a place and time when diapers were not disposable, they were fastened on with a safety pin—fabric diapers,” she explained frankly, giving a clue to the climax of the scornful ballad. Comically singing of the woes of a contempt woman, McLorin Salvant gripped the audience with every lyric, singing, “Completely square is my true love’s head/He will not marry me, no, he will not marry me,” with such intensity that she received a wedding proposal from a fan who yelled, “But I will!” briefly halting her singing as she shyly hid under her vibrant yellow Issey Miyake bolero jacket, using it as a makeshift hood. The audience cheered, and McLorin Salvant continued the story, singing, “Rectangular is the hotel door my true love tried to sneak through/Rectangular is the transom over which I had to peek through/Rectangular is the hotel room I entered angrily/And rectangular is the wooden box/Where lies my love neath the golden phlox/They say he died from the chicken pox/In part, I must agree: one chick too many had he!”

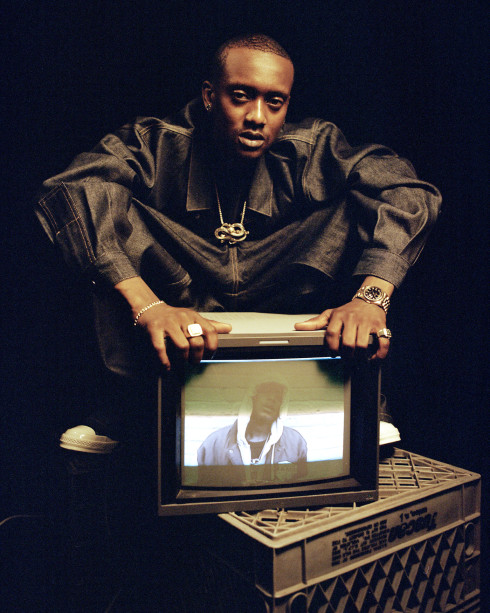

Primed this year alone by Netflix’s critically acclaimed What Happened, Miss Simone? and HBO’s Bessie (the soundtrack of which features McLorin Salvant), we may be at a point in pop culture where jazz is finally positioned to circle back. In music, the jazz bones of Kendrick Lamar’s To Pimp a Butterfly and Flying Lotus’s marriage of jazz and hip hop on last year’s You’re Dead are stepping stones for the reacceptance of standard jazz by the younger demographic that once made the genre and the culture what it was. But still, there is a disconnect because of our preconceptions about contemporary jazz. “Jazz is not seen as an alternative music, it’s seen as a dusty, old thing,” says McLorin Salvant. “There are so many instances of people saying, ‘Jazz is dead.’” Yet for her, it is full of life. “I think most of those songs have this timeless quality to them; there is no real reference to time,” she says. Now it is up to the audience to embrace the new voices and faces of jazz as they revive and reinvent that golden age, because if we’re going to bring back jazz, it’s going to take someone like McLorin Salvant to make it happen.

For One to Love is out now.

- By

- Yelena Perlin

- Photography by

- Hector Perez