All images courtesy of the artist.

CYRIL HATT

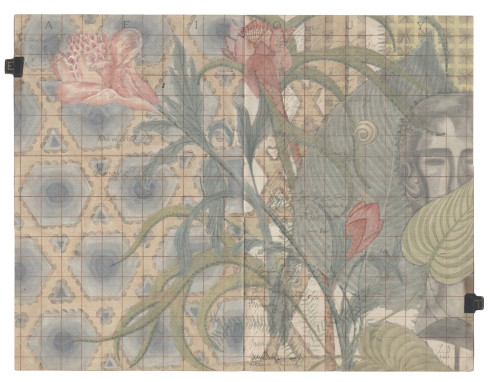

If you are interested in the way art is stored, the methods of Cyril Hatt will elicit some curiosity. The Frenchman makes works so large and fragile—paper-thin sculptures held together by office staples and propped up with wooden sticks—it’s difficult to imagine a facility vast enough to keep them in. Who lovingly dusts Hatt’s glossy, fractured pieces or fits a plastic covering around them? Who checks this building for mold and visiting insects? Who ensures that the biggest works, say a replica car made from one thousand postcard-sized photographs, keep their intended form over months and years without capitulating?

Hatt’s archives function less as you’d imagine (a sculpture-stuffed warehouse) and more like an ordinary library (of the Dewey Decimal variety). This may seem odd, for one thing, because his torn, lacerated, savage reconstructions are always built in 3-D—they’re puffed-up papery “copies” of everyday articles like shoes and alarm clocks and disposable razors. To save room, Hatt puts them into wooden tubes. “The car sculpture doesn’t stay a car sculpture in my studio. I remove the wood sticks that make it stand until only the paper remains. Then, I just fold it all up to be reopened like a pop-up book.”

Before their rough assemblage, Hatt’s sculptures exist as stacks of photographs, ordinary and unglamorous, ordered as standard 4×6 prints online. (An emailed image of Hatt’s bookshelf serves as a reference point, showing five shelves filled with rows of prints, stacked tightly, just like books. On the top shelf are a series of storage containers and a framed image of the Virgin Mary.)

In making his almost-copies, his optical transmutations (including the sculpture of a cake by London baker Lily Vanilli for our Fall 2015 issue), Hatt achieves a few things. He meditates—whether willingly or not—on a familiar theme, the abundance of consumer junk late capitalism has produced, all that internal white noise produced by catalogues and commercials and paid-for posts and dreary flat-lays. He reflects on the physicality of the photograph, something increasingly stored as digital information, bringing a conclusion to the action of capturing a thing or moment. Further, he grants himself permission to be rough and physical with printed images, the forbidden fruit of his childhood. “The 4×6 size reminded me of family albums my parents had when I was young,” he explains. “Photographs would be cleanly stored. You couldn’t touch the paper; otherwise, it would leave marks on the photo. My first work, the first attempt, was to look at these images that were considered almost sacred, put fingers on them and leave marks, to fold them and allow them to take volume.”

Fortune delivered Hatt into the arms of Alber Elbaz, Lanvin’s long-reigning and lauded former artistic director. According to Hatt, the genesis of their union was fairly ordinary: a Lanvin employee knew Hatt’s gallerist in Paris and introduced Elbaz to the work. He liked what he saw, and in 2008 the pair started working together on presentations and sets and high-impact window installations in a pleasing amalgam of art, fashion, and commerce. The latest iteration was for the house’s Resort 2016 presentation, where models posed against Hatt’s backdrop of crumpled ink-jet images shaped into gleaming—and sometimes savage—approximations of rarified stuff: a red Alfa Romeo, a single Somali giraffe. As one Vogue writer put it: “Here is where Elbaz is truly clever, beyond his genius at creating clothes that women love to wear…that set, for all its shine and inherent hollowness, could have been knocked over by a stiff breeze.”

According to Hatt, the jobs with Elbaz happened like a conversation between friends, an unguarded dialogue where both could feel around in the dark without fear. “He looked at my catalogue and requested pieces, but there was a lot of freedom to change objects. There was a red car, for instance, that was first presented for [Lanvin’s] showroom, where it looked like a car. The second presentation was for the shop window on Madison Avenue, a much smaller, narrower space. We completely destroyed it, forged it into split pieces of metal, as though it was in an accident.”

Hatt has had no formal training. He came to art after exhausting several other career options. He tried English literature (at university) and taught French in the United States (“I was not pedagogical. That sense, it isn’t developed within me”). People he knew went to art school, but he isn’t sure he would have flourished among all that competition. Paris is very competitive, Hatt explains, and artists can be guarded with their ideas. Perhaps there is some merit to this attitude—he tells me another artist once copied his sewn-together style, and while the incident didn’t bother him, it’s certainly remembered, and, by the way, the irony of imitating a man who himself produces imitations does not appear lost on him.

There’s a cultural disconnect that rears its ugly head when viewing early works of Hatt’s, some of his first to employ printed photos as raw material. This is our fault more than his, a product of references proving too hip with time. In subject matter, they overwhelmingly mine the now-unfashionable era of fetishized nostalgia: there are cassette tapes and boom boxes and plastic-bodied Diana cameras. Hatt’s recent output feels darker and somehow more satisfying, like 3-D scans chewed and spit out (for instance, there’s his brooding, ominous altarpieces). At the time of our interview, he was attempting his first humans.

“I’m not entirely satisfied with the results,” Hatt concedes. “The representation of skin with staples has torturous connotations, something Frankenstein-ish. But everything that is natural and round is difficult. Fruit, for example. Sometimes changing the scale helps, it alleviates the mimetic feeling and gives me more freedom in composing. An exotic fruit realized in a larger scale becomes completely new, almost abstract.”

From his home and studio in the very pretty Saint-Jean-de-la-Blaquière region of France’s south, Hatt looks after his children. He works busily, producing his meditations on a theme, every sculpture messy and genuinely felt, every accident as relevant and important as a deliberate action, every image remade from memory. “It’s funny how you mentioned Hans Ulrich Obrist during the interview,” Hatt says, in an email later on. “Yesterday he just posted a quotation of Richard Hollis, which said, ‘On it’s way to being stored all memory becomes fiction.’ That does ring a bell for me.”

All images courtesy of the artist.