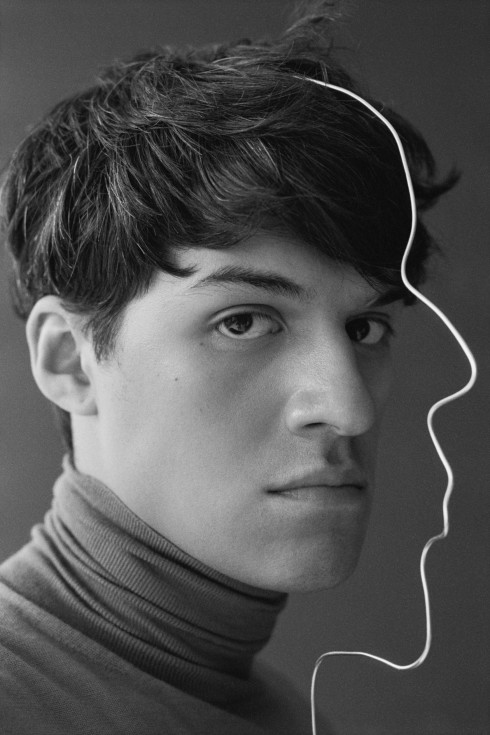

- By

- Brady Donnelly

- Photography by

- Patrick Lindblom

Styling by Ianthe Wright. Grooming by Antonio De Luca. Photographer’s assistant: Simonas Kuzmickas. Stylist’s assistant: Leona Burton. Digital technician: Jim Tobias Johnston.

DERMOT KENNEDY UPDATES THE IRISH FOLK TRADITION WITH THE PASSION OF HIP HOP

First, some good news: Singer-songwriter Dermot Kennedy has never pinned himself as Ireland’s answer to Drake, though the music industry itself is eager to do so. Still, the similarities are there. His songs tend to build from a sound rooted in Irish folk, his lilt towering over an acoustic guitar, toward something more complex, more multigenre. Sometimes, it’s simply that the pace picks up, his lyrics unraveling near double time, but more often, it’s the drop—the moment the drums come in, heavy, commanding, and insistent, like a hip hop beat over which he has masterfully layered a fuller composition.

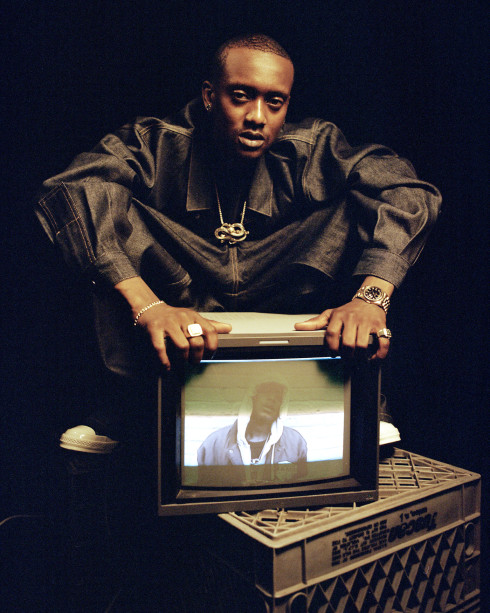

This is to say that a parallel can certainly be drawn, but it may be a bit dated. If you ask Kennedy, whose new EP, Mike Dean Presents: Dermot Kennedy, came out earlier this month, he’ll tell you that he’s not pretending to understand the urban American experience at the core of hip hop. His collaborator Mike Dean is a legendary hip hop producer, sure, and Drake is a primary source of inspiration, but both Bon Iver and Irish folk legend Glen Hansard are idols. A quick listen would make clear that Kennedy pulls from the latter two his sound and sometimes his lyrics, and of Drake, he’ll say he is inspired by his honesty. “Part of the reason I love rappers and hip hop is that it feels like really organic music,” he explains. “I’m obsessed with just trying to express myself and right now, that’s with a guitar. I feel like maybe I can relate to that in hip hop artists—it just feels like it’s something that’s part of their body.”

So Dermot Kennedy doesn’t want to sound like a rapper. He wants his music to sound like it’s part of his body and that honesty just happens to exist in hip hop more than anywhere else. If you’ve seen him live, where a sparsely scattered discography is sung by fans word for word, you’ll know he’s achieved it. In a world where technology is used to mask recorded impurities, allowing for perfectly in-tune recordings and uncomfortably out-of-tune performances, he may actually sound better live than he does on his albums. On stage, his voice—dense, impassioned, often gravelly—is almost orchestral in its fullness. At those moments, he’s pulling from the source: “You can almost use it, that angst or whatever you’re feeling, when you perform,” he says. “If there’s one line in the whole song that hits me, it’s enough for me. Not everything can be an absolute winner, a universal truth for everybody. If I’m not feeling so great, it often adds to [the performance].”

Of course, Kennedy’s reality is much different than that of his American counterparts. Materially, it’s an ever-present Ireland—a seemingly constant dusk, a backdrop of cliffs, coastlines, and sea. Immaterially, though, it’s a complex internal conflict. Where Kennedy excels as a songwriter is in addressing the human tendency to protect ourselves against pain by avoiding new experiences altogether, pushing, as he does in his performances, against that need for self-protection. He points to Michael Stuhlbarg’s powerful speech towards the end of Call Me By Your Name, in which he warns his son Elio against the foolishness of “making yourself feel nothing so as not to feel anything,” as the purest summation of this idea. In “Glory,” he himself calls this up-and-down “an old refrain,” but his unpacking is more multi-layered than that; it’s a tendency to weave between the two sides of the conflict, making the back-and-forth the subject itself. In “Moments Passed,” a single he released last year and had remixed by Mike Dean on the new EP, he sings: “‘Cause I loved you/Does that mean nothing to you now/I loved you/Get me back on homely ground/She said, ‘Oh, I know that love is all about the wind—how it can hold me up and kill me in the end. Still, I loved it.'”

At twenty-five, Kennedy is primed to explore this subject matter: young enough to feel the full impact of every gesture, however minor, yet old enough to question the worthiness of repeating it. In person, he calls it a “willingness to feel something” and a “pain that carries through anything you do,” and in his best work, he doubles down on that search for feeling as a primary driver, not an inhibitor, of day-to-day life. In “A Closeness,” he sings, “Keeping her bright eyes focused on the coastline waiting for you/Isn’t she all of us pining for that last kiss, a permanent truth, a means to get through?/Maybe we’ll cry whilst hopeful when we think about the past being cruel/Got a thought for those who start to think of love as the pursuit of a fool: It’s a palace from ruin.”

Naturally, life has changed drastically for the Dubliner in the two years since his self-recorded tracks gained momentum on Spotify, propelling him from busking to playing sold-out shows in his hometown’s famed Olympia Theatre. That return to his city was the culmination of an effort that extends back into his early teens, when he first began to see “the guitar and the piano as a vehicle for getting [my lyrics] across,” through a college career in which immersion in more classical training first delayed, and then, he accepts, made possible the technicality for which he is known today. Still, when he finally branched out on his own, it wasn’t tradition and training that restrained him, but the industry itself.

“I was actually trying to make money to record at home, because I’d gone to the studio a couple of times and the producers were manipulating it too much and it became something it wasn’t,” he says. “Eventually, I made enough money, I realized I didn’t want to spend time learning how to produce myself, so I went into the studio with a super clear idea of what I wanted to do.” He built his name on the songs that came out of those sessions, with no magic formula outside of a bit of self-determination, and they’ve propelled him in rapid sequence to a period in which the process is much different, somewhat more refined. The freedom allowed by anonymity, when he could write and record when and only when inspiration struck, is not always there, but in its place are types of access unavailable in his days as a student and busker.

“When I was writing songs before, it was like, This is all I do, and it comes out in January or April and no one gives a shit,” he remembers. Now, he continues, the stakes are not only higher (his fans have started tattooing his lyrics onto their bodies) but the window to write doesn’t always align with the therapeutic need to write. “To be in a scenario where you’re in Los Angeles writing for two weeks, to feel it—I don’t know if I can,” he admits. Surveying from the other side, though, as he tends to do, he adds, “To get to go to Los Angeles and work with certain writers, it equips you with so much stuff for when you are at home and you become a better writer.” He believes he owes much of his success to a release cycle more in favor of singles than EPs and he defines his most recent work as a mixtape. Selflessly, he embodies an industry shift toward a less structured, less cyclical process and his pathway to success suggests that the openness of the internet actually puts pressure on the musician to define his or her own route forward. The record company formula—record, release, tour, and repeat—is an option for those shaped for manufactured pop, but not for someone like Kennedy.

Of those earlier days, he says, “You put EPs out or collections of songs and you put them on social media, your family and friends share them, you get a couple hundred listens, you get texts from friends being like, ‘Oh, this is really great,’ but it always gets overlooked.” He continues, “So, I was like, I’m going to avoid that really deflating feeling and just put these up one song at a time. I’m really happy with them, and I’m just going to do them one at a time. When you do that, you’re not trying to do anything like get an email from a record label. It’s like, I recorded this song. Here it is, you can have it.”

Having recently wrapped a North American tour, Kennedy is looking eastward for a window in which he can record a full-length album. That, he says, needs to happen at home. “It’ll feel really nice to reclaim some of that Irishness when I’m home,” he says. “We have such a lovely lineage of songwriters from Ireland. I want to be part of that. I don’t want anyone to forget that I’m very much Irish.” How Kennedy is reshaping that lineage is yet to be determined, but he has the cosigns he needs to carve the path he’s forging. If there’s a component of Irish lineage he’s extending, it may simply be a Joycean tendency to make art of a form all his own.

Mike Dean Presents: Dermot Kennedy is out now.

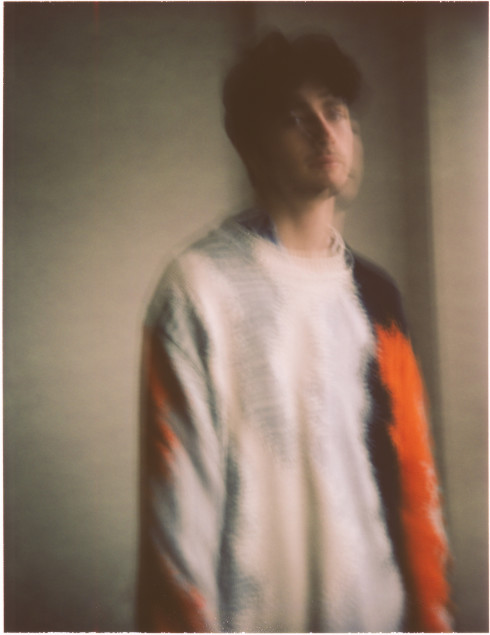

- By

- Brady Donnelly

- Photography by

- Patrick Lindblom

Styling by Ianthe Wright. Grooming by Antonio De Luca. Photographer’s assistant: Simonas Kuzmickas. Stylist’s assistant: Leona Burton. Digital technician: Jim Tobias Johnston.