- By

- Annette Lin

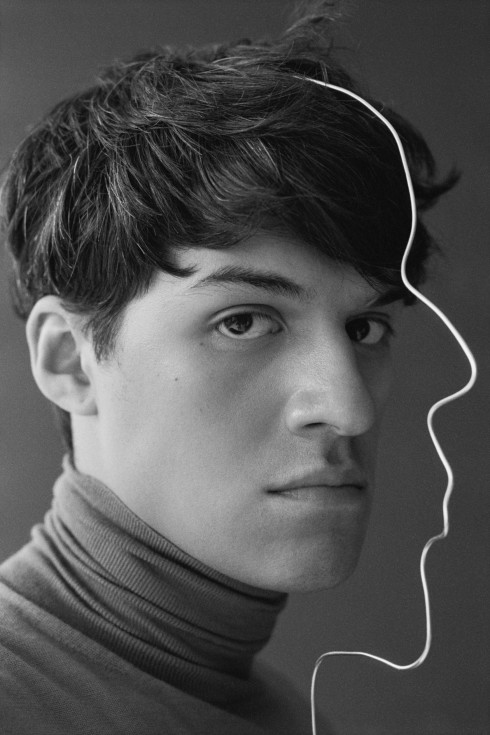

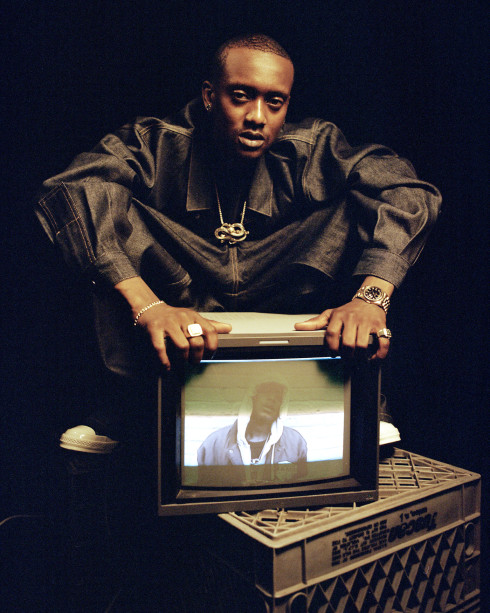

- Photography by

- Gabriela Celeste

Styling by Anthony Pedraza. Hair by Eloise Cheung at Kate Ryan Inc. Makeup by Miguel Lledo at Artlist.

JAY SOM

On a Thursday night in September at Bowery Ballroom, a packed room waits for Jay Som to take the stage. A girl appears; the crowd stirs. “Give a hand for Jay Som!” she shouts, as she sweeps her hands together to clap and nods to the crowd to follow.

Jay Som, whose real name is Melina Duterte, comes out a few seconds later, and the audience goes appropriately wild. As the set starts, the crowd listens with such rapt attention that it’s clear Duterte didn’t need someone to warm them up. Duterte, who is twenty-three, performs with an easy, intimate charisma that’s hard to look away from. She’s preternaturally relaxed with the crowd; whether she’s speaking or singing, it’s with the comfortable familiarity of a friend who’s used to spending school holidays at your house. Even though her bandmates are friends from growing up in the Bay Area—she calls them out throughout the night: Oliver Pinnell on guitar, Zach Elsasser on drums, and Dylan Allard on bass—they are still relatively new to touring together. But the jokes they throw around on stage make it seem like they’ve been touring as a group since kindergarten.

Everybody Works, her début album released earlier this year, inspires the same intimacy. Overall, the record exudes an effortless, pleasantly hazy indie pop vibe. Songs like “The Bus Song” and “Baybee” are laid-back and dreamy, with assertive beats woven in with Nineties synth melodies—songs you would listen to on a lazy afternoon. “One More Time, Please,” her favorite—“It was really fun to make,” she offers—is legitimately danceable, while “Take It” and “1 Billion Dogs” channel the punk-rock ambience of her first collection, Turn Into. The opener, “Lipstick Stains,” seduces with its sleepy, orchestral sound and the album finishes with the lush, downtempo “For Light” that drifts off gently with vibrato electric guitar. The effect is atmospheric and emotionally rich, like a Beach House album, albeit with more energy.

Over a few decades in the late twentieth century, the avant garde playwright María Irene Fornés won nine Obie Awards (the equivalent of Tony Awards for productions produced Off Broadway) partly due to her ability to condense the emotional density of life into plain, easily relatable phrases. Duterte’s lyrics have a similar effect; her words are simple on the surface, but tap into universal human experience with surprising clarity. In “The Bus Song,” about the end of a relationship, she sings, “Why don’t we take the bus?/You say you don’t like the smell/But I like the bus,” encapsulating the small differences that contribute to a separation. She finishes the verse with, “I can be whoever I want to be.” Duterte sings about things we’ve all been through, whether we want to think about them or not.

Duterte has been a musician since her childhood, and a career in music was not so much an act of serendipity as a calling waiting to happen. Even though no one in her Filipino-American family was a professional musician, she grew up surrounded by music, particularly in the form of karaoke. She started practicing at the age of eight, teaching herself to play using tabs from the internet with a small acoustic guitar. At school, she fell in love with the trumpet—her interest was first piqued because “it sounded fun”—and she went on to train classically in trumpet for nine years, while expanding to instruments such as the keyboard and the drums at the same time. (She played each instrument on Turn In.) “It’s hard to think of what other direction I would have taken [without music], it’s just been my entire life,” she says. She started writing music because she was “just pretty curious at a young age,” she explains. “I was just listening to guitar-based bands and I remember thinking I really wanted to do that—and I felt like I could.”

Which isn’t to say her rise has been smooth sailing all the way. Like plenty of artists, Duterte has had to deal with plenty of less-than-ideal jobs; the worst, she says, was “when I worked at this deli at Ocean Beach and the owner was a straight-up racist homophobe. He was also in the closet too.” The album’s title track, “Everybody Works,” is a three-minute ode to the fact that nothing in life comes easy. “Hey, you’re a rockstar/But do you have the time?/Did you pay your way through?/The right place, the right time?” she sings softly, before moving to the chorus: “Try to make ends meet/Penny pinch till I’m dying/Everybody works.”

Perhaps the main thing that has surprised Duterte has been her rapid ascent. She uploaded Turn Into to Bandcamp at the end of 2015; by 2016 she was touring as a support act for Peter Bjorn and John as well as fellow Asian-American acts Mitski and Japanese Breakfast. This year, she is headlining, and performed an NPR Tiny Desk Concert in July with her bandmates. “I thought it was going to take five years,” she says of her progress. She finds the pace, understandably, overwhelming. “It’s harder when you’re headlining. You’re always last so you end up playing late and you load up really late, and you don’t get sleep, so it’s not very glamorous,” she says. “I’m very much a homebody with music. I really like to be by myself in a room, recording.” But when asked what she’s found the hardest so far on her musical journey, she offers: “I think one of the biggest things is it really takes a lot of effort and hard work to get to where you want, but it’s honestly ten times harder to maintain it when you’re there.” Not that she would ever change her mind about her chosen path. “I do want to become a little better with engineering and producing,” she admits, “but I just want to keep doing music forever.”

Everybody Works is out now. Jay Som’s North American tour continues tonight at the Bluebird Theater, Denver.

- By

- Annette Lin

- Photography by

- Gabriela Celeste

Styling by Anthony Pedraza. Hair by Eloise Cheung at Kate Ryan Inc. Makeup by Miguel Lledo at Artlist.