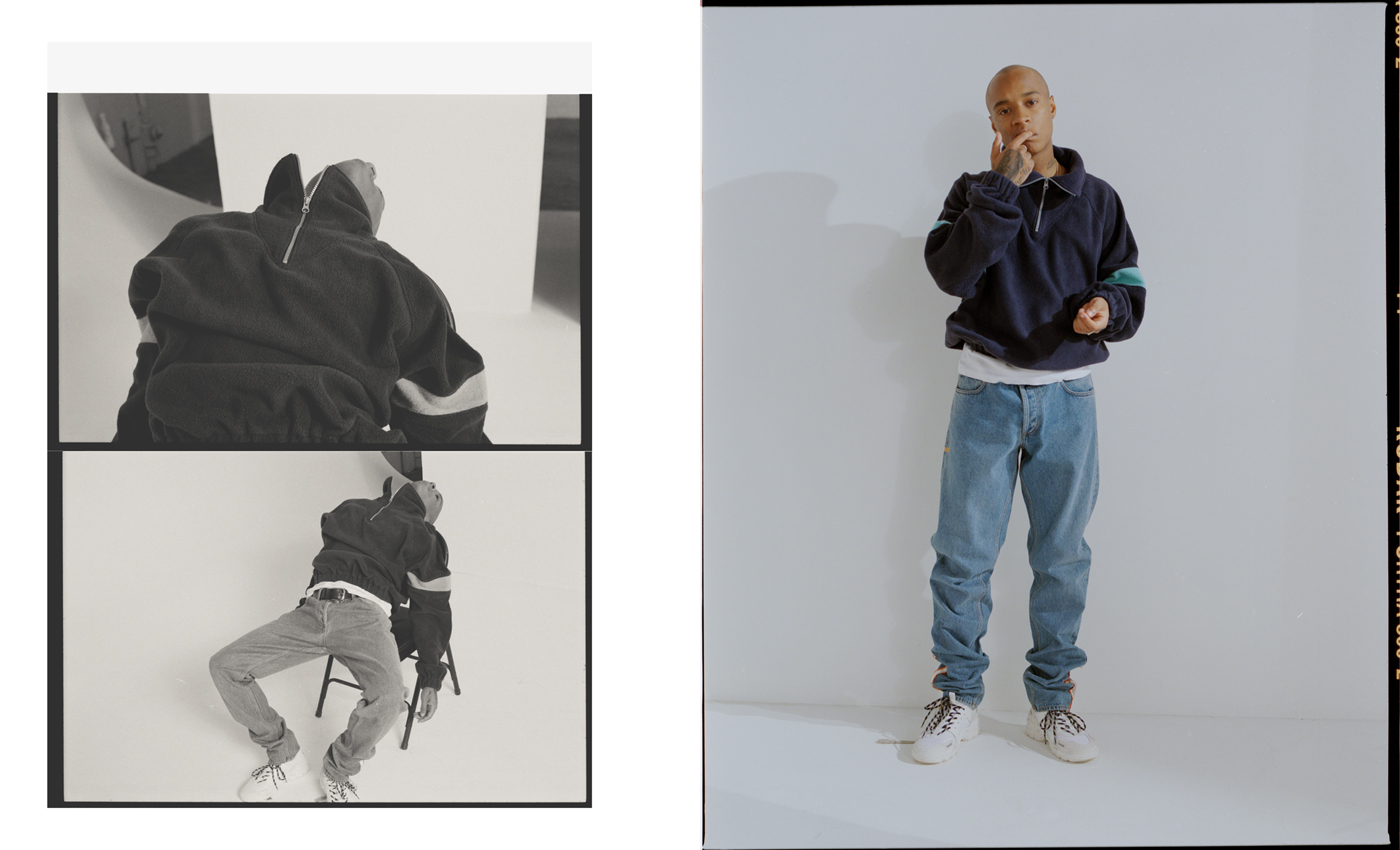

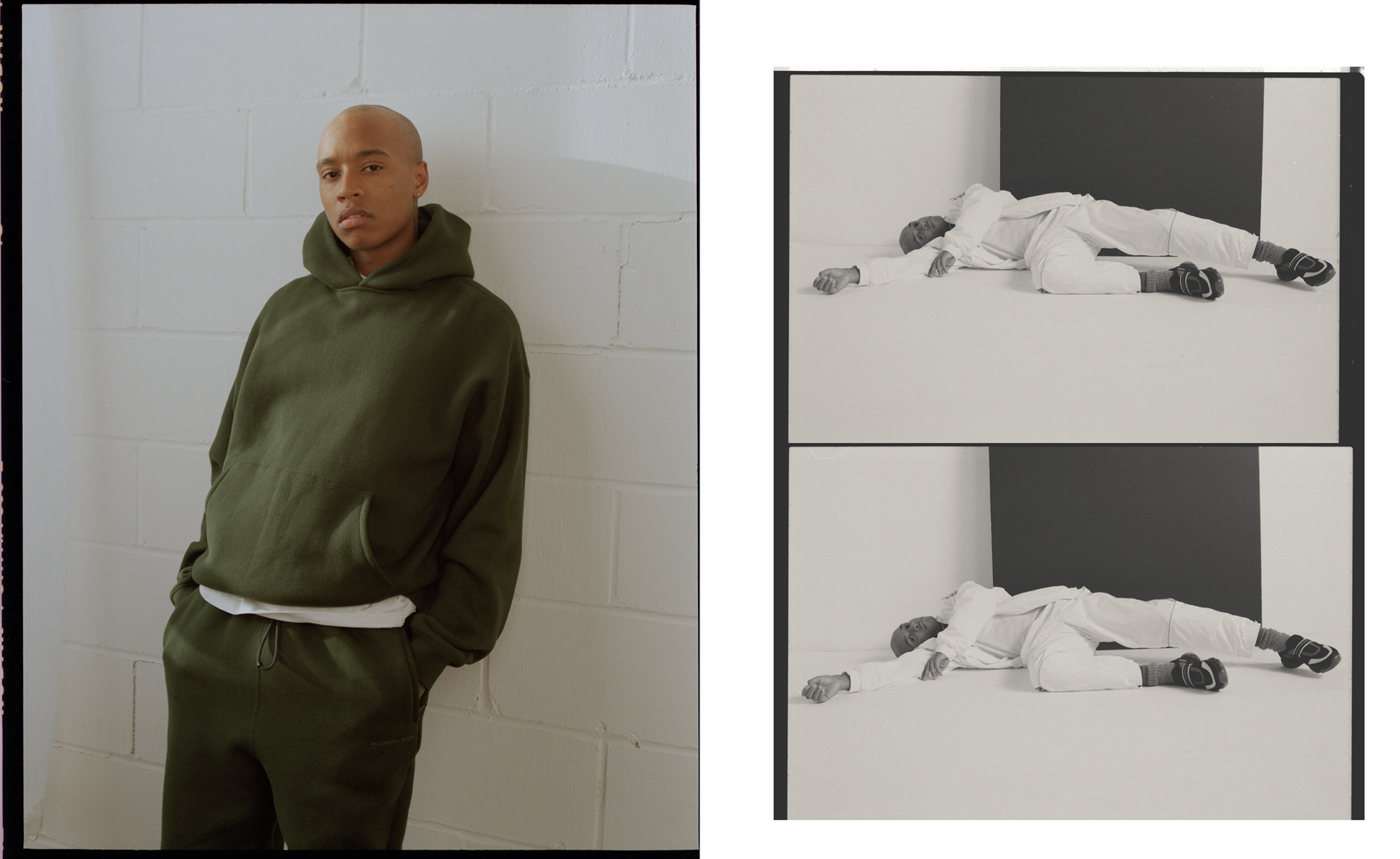

All clothing by Gosha Rubchinskiy. T-shirt, hat, and all jewelry throughout; talent’s own. Sneakers by Prada.

- By

- Janelle Anne

- Photography by

- Davey Adesida

Styling by Thistle Brown. Grooming by Dana Boyer at Art Department. Photographer’s assistant: Tyler Kuffs. Stylist’s assistants: Ian McCrae and Julius Frazer.

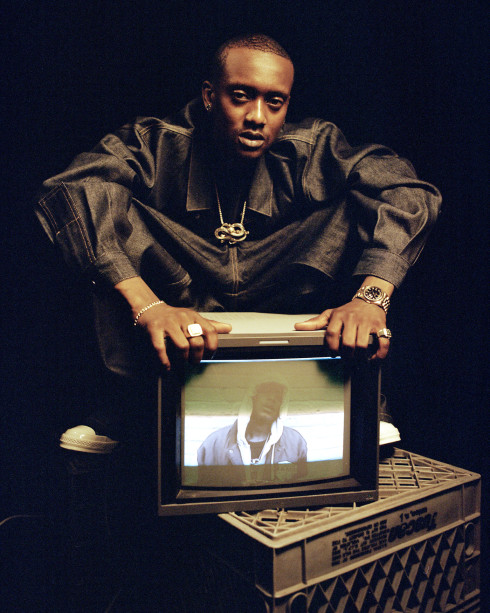

REJJIE SNOW BREAKS THROUGH HIP-HOP'S LIMITS

“Hip-hop kind of happened by accident,” says the 24-year-old Rejjie Snow, who introduces himself by his real name, Alex (last name: Anyaegbunam). “I guess it was just always there because I was the only black kid in my group.”

Anyaegbunam grew up on Dublin’s Northside with a Nigerian father and an Irish-Jamaican mother who both nurtured his independent streak. His friends, who were all white, listened to techno, but also introduced him to hip-hop through video games—Grand Theft Auto and Tony Hawk brought him to Wu-Tang and Nas. He left Ireland at age sixteen, after a stint of getting in trouble for painting graffiti, and moved to London, where he quickly found friendship with collaborators like King Krule. Anyaegbunam now lives wherever he suitcase takes him, usually between Bushwick and the British capital.

Like a black man with an Irish accent, the cover art of his first album Dear Annie, released last month, also elicits curious expressions. Picture a red-headed toddler framed by a verdant lawn—and you’d never guess the kind of sound contained within. As someone who often begins his creative process with an image (or feeling or experience), Anyaegbunam himself can hardly commit to the hip-hop genre entirely. Many of his influences come from the movies, no surprise given that he nearly went to film school. “I wanted to make dark films,” he offers. “I wanted to make people feel uncomfortable.”

But Dear Annie does not sound like the score to a thrasher movie, though there is no shortage of thrill or psychological depth. There is a filmic quality to the tracks, designed by the likes of Kaytranada, Cam O’bi, and Grammy-winning Kendrick collaborator Rahki, best listened to in sequential order as reinforced by the radio intermissions between songs. “I tried to make it really cohesive to the point where you don’t skip any songs and you’re really thrown into this world,” Anyaegbunam explains.

That world of an album, conceived and recorded on the road between Paris, London, and Los Angeles, is Anyaegbunam’s magnum opus, collecting all of his influences in one sound—including the contradictions and conundrums he embodies. Take the song “Rainbows,” named after an arc of illusion, prevalent in the land of leprechauns. Birds chirp to the happy, bouncy melody as Anyaegbunam’s soft, mumbling baritone grounds all that levity: “I’m a star, I’m a king, I’m a champion to those/Black face, black taste, and I got black hoes.” There is the sense that Anyaegbunam’s music occupies a different kind of blackness, one inclusive of people who look like him and inclusive of people who like the creative output of people who look like him—aka the diaspora of hip-hop fans.

This is not to say that Anyaegbunam makes music for white people, as the hip-hop establishment can sometimes be quick to claim, but he has had his worries about being rejected by the hip-hop community solely because of his Irish heritage. This self-awareness informs his music, but doesn’t define it. His response to the conventional narrative is equally rare. “It’s not annoying to be asked about race,” he shrugs, “but I don’t think about race a lot—not in terms of meeting people.”

Anyaegbunam seems to understand the codes of American hip-hop parochialism. When an entire genre is so rooted in the socio-political experience of black and Hispanic Americans, his conscious dissociation from genre identity makes sense. Hip-hop, as perpetuated by its creators and consumers, is spoken from the kind of personal experience that Anyaegbunam acknowledges he didn’t have growing up. And that is something he respects. The genre’s familiar bravado does come out, albeit quietly between songs: “I’m Irish, but not from the waist down.”

He is being touted as a scene unto himself, compared to other nonconformists like Anderson .Paak, Thundercat, and Shabazz Palaces, but perhaps what really sets him apart is not the presence of complexity, but rather the absence of needing to prove himself in the black-and-white world of hip-hop, the freedom from having to argue that just because he’s black doesn’t mean his music has to be defined as such. “I like to keep my music subjective,” he explains. “In the process of making this album, I was trying to find my identity through music: being young and all that shit.”

The last song on the album, “Greatness,” featuring Atlanta soul-singer Micah Freeman, is essentially a four-minute history lesson in the journey of Alex Anyaegbunam thus far. It’s full of twists and turns, as paradoxical as expected. Between an optimistic chorus (“Momma, you told me that everything’s gonna be fine”) and nods to struggle (“Living out dreams ain’t what it seems”), we get the sense this album is the soundtrack to his particular coming-of-age story, as much as it is the rite of passage for someone who cannot be simplified in the public consciousness. It’s perhaps a sentiment we can all identify with.

Dear Annie is out now.

- By

- Janelle Anne

- Photography by

- Davey Adesida

Styling by Thistle Brown. Grooming by Dana Boyer at Art Department. Photographer’s assistant: Tyler Kuffs. Stylist’s assistants: Ian McCrae and Julius Frazer.