- By

- Janelle Anne

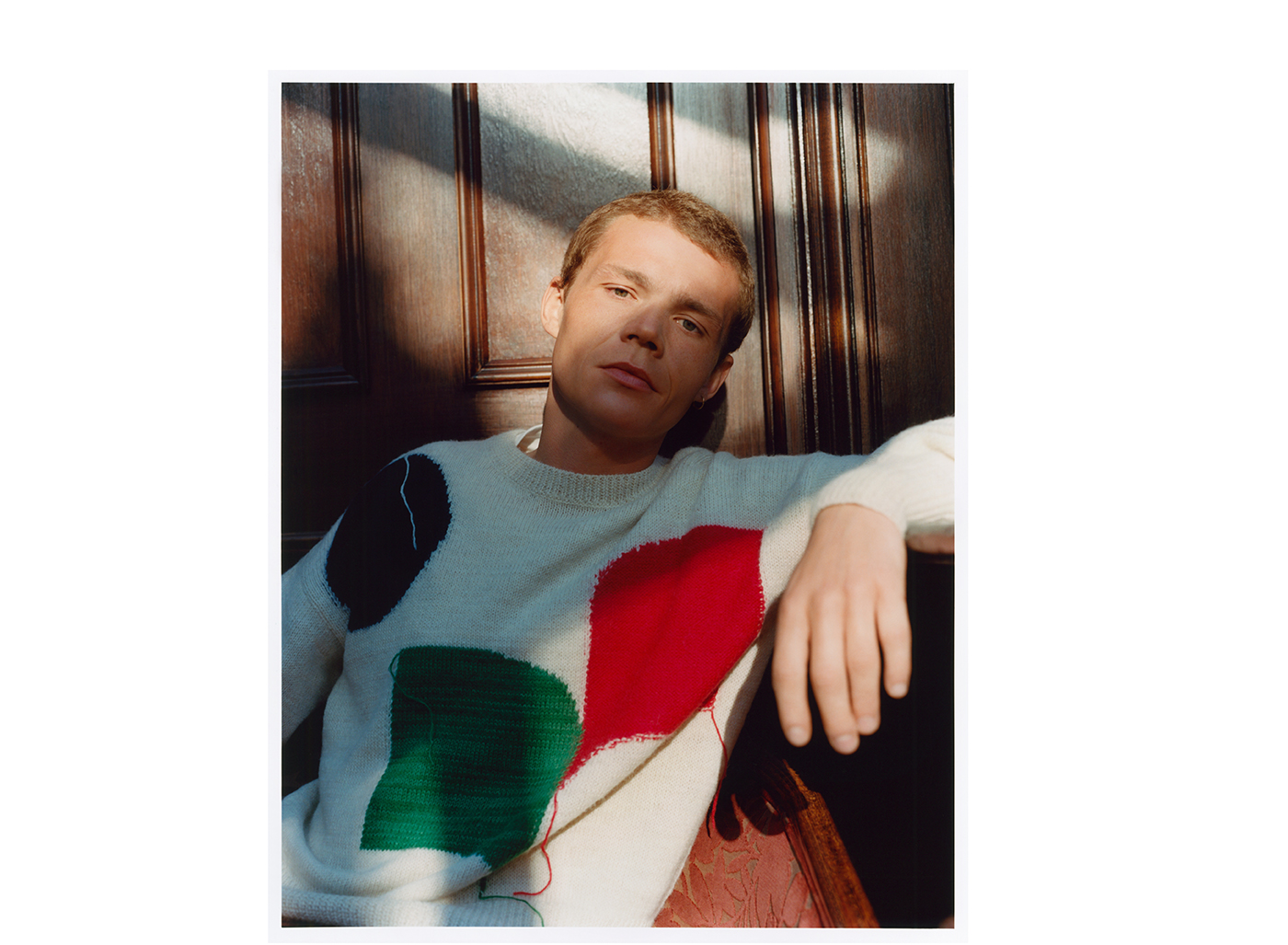

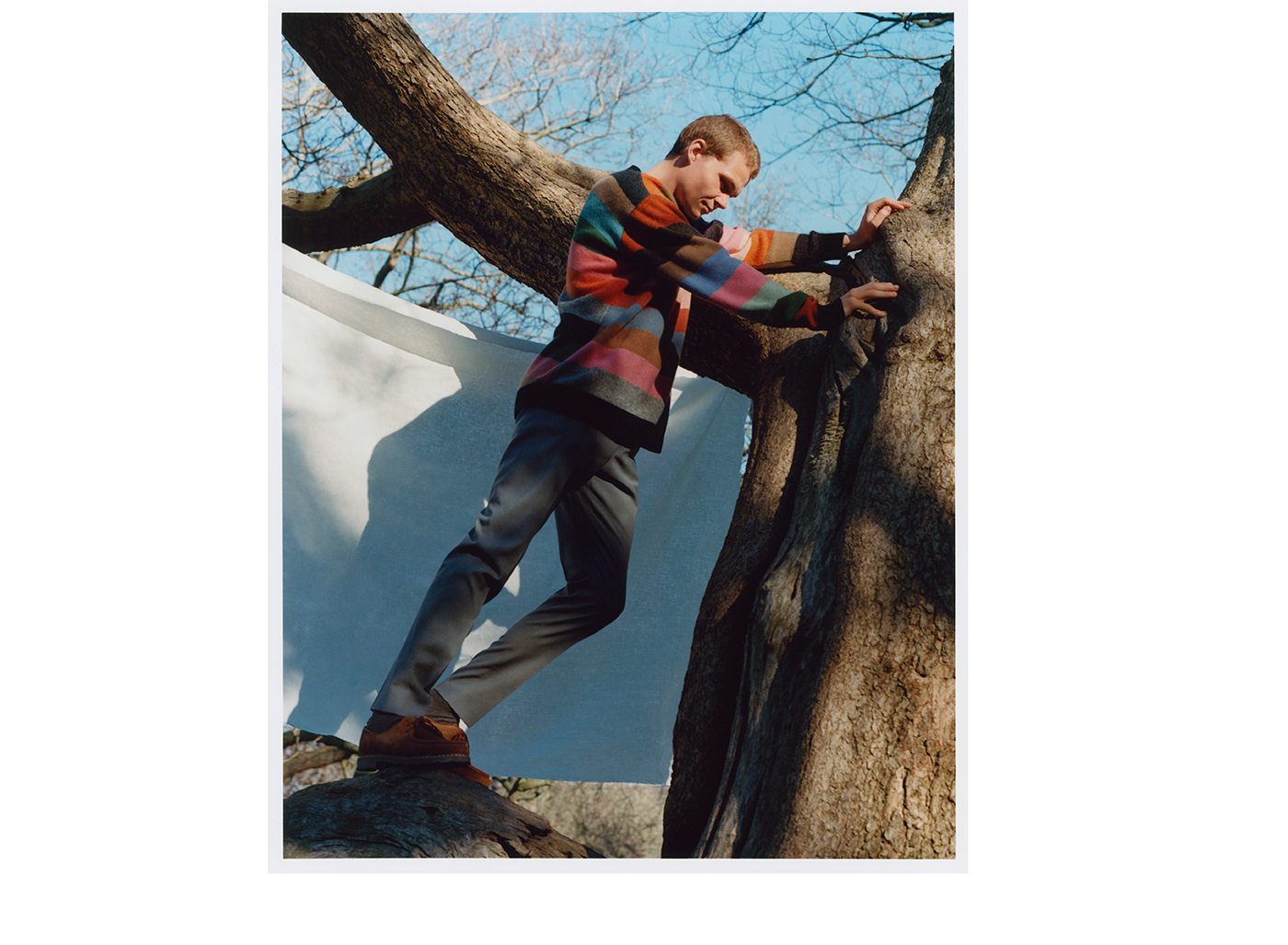

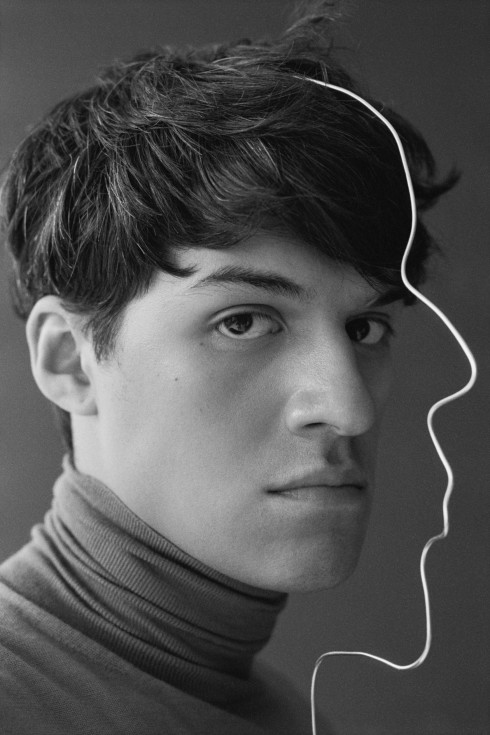

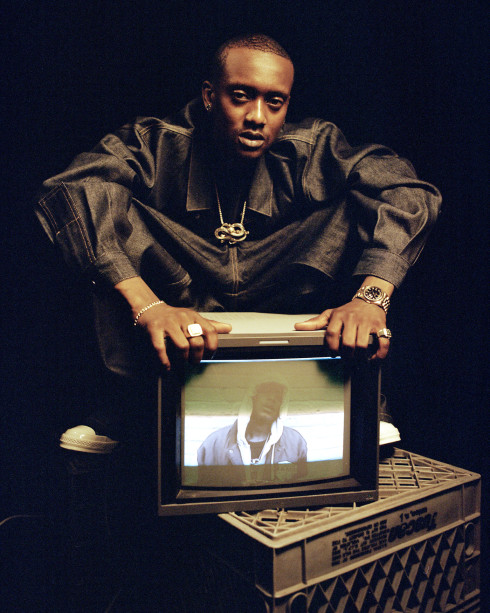

- Photography by

- Julien Tavel

- Styling by

- Laetitia Paul

Grooming by Philippe Miletto. Photographer’s assistants: Andrei Topli and Theodora Papanikita. Production assistant: Amanda Merlo. Postproduction by Art Post.

Westerman Turns Sadness Into Art

“I could live in this song,” I vaguely remember someone saying in the group chat the day I discovered Westerman. Even though it was just a few months ago, the memory is a blur because the rest of the day was marked with constant replays. The song is “Confirmation” by Will Westerman, a singer-songwriter from London who goes by his last name and who used to hide behind his long hair. His most-streamed track on Spotify (to which I contributed significantly that day), “Confirmation” feels tensely comforting. His current electronic folk sound embodies a phantom quality that most people understand as dreamy and introspective, making it perfect for big headphones, solitary commutes, spacing out—or any situation that envelops you within an emotional space, protected from the woes of the world. It’s a space not everyone is comfortable visiting, fearing the honesty of inner monologues. Instead, most people seem to prefer to reverberate music into their skulls until they reach a state of non-thinking. Or at least until the narrative they used to tell themselves is now transformed, enchanted even, by an elegant recording of trapped air. Needing confirmation, I asked Westerman over email.

He wrote back, “I think maybe that’s right—it is a sort of meditation when you get into a good flow of music. It’s unconscious.”

“My music is engaged with questions a lot of the time,” he added later.

I learned afterward that “Confirmation” was written after Brexit and Donald Trump. Depression had ensued. I did not ask for more details, but it’s easy to picture what Westerman was going through, abstractly with an acknowledging, distant nod. The events of 2016 created new genres in music and art which history will remember as either acts of resistance or meaningless reactionary fluff depending on what unfolds. Westerman’s music, however, functions a bit differently, especially since it was released two years later. There’s now a kind of nostalgia attached to it. A bittersweet upheaval of emotions related to trauma and turmoil weirdly also makes you feel again—whether they’re from a love scorned, a death mourned, or a bubble torn. Is it a confirmation of the absurdity of being alive?

As someone who writes about musicians from time to time, I am interested in contrast because it can be measured as dissonance and tension. Sounds are interpreted into visuals, and visuals into words, which seems like a good formula for describing the invisible. But unlike invisible feelings or ideas, sound arranged into patterns is one way the brain mulls over things we all know and feel but can’t quite communicate with the same conviction as seeing. (Blame evolution.) It seems Westerman thinks similarly. “I see melodies and lyrics as the central sketch of a painting and the production around it kind of like a palette,” he says, “the colors you surround and fill it with.”

He hasn’t released a full-length album yet, but he’s working on one now while on tour. “I hope it’s going to sound quite distinct and give a fuller picture of the world I see. I want it to be an album you can live in,” he offers. “I’m excited by all of it! I hope it can be useful.”

Like most people, external validation was what initially drew Westerman to music. “I think I just started with guitar to try and impress girls probably,” he recalls. “Then quickly I started making it and it just felt good in and of itself.” He adds, “The ability to bring disparate tribes of people together over something is exciting for me.”

A few days after our discussion, I saw the disparate tribes for myself, including the tribe from the group chat who led me here. People trickled into Rough Trade, a sizable venue in Brooklyn with a store in the front, perusing the new-ish space filled with shrink-wrapped records that have somehow survived the digitization of music. Thanks to a few smart bets on the vinyl resurgence, here was a place where people would actually hang out, screens be damned. “The audiences [in the US] are much more vocal between songs but really quiet during them, which was good as it hopefully means people are having a good time but also listening quite intently,” says Westerman. “That’s a good balance for me.”

This particular performance was more of the same listening. I stood at the balcony, watching people watch the stage. Westerman quietly slipped in and might’ve gone unnoticed if not for his bright orange long-sleeved shirt and a slight wave. With little introduction, he and the band began with a new song from the new record.

His voice reverberated with a soft gravitas, reaching for a new place on your palette. Between songs, his speech was a little less smooth. The second guitar was broken so he grabbed a capo mid-apology, stepping away from the mic as if forgetting no one could hear him. The audience smiled back as if to say, “It’s ok, please keep singing.”

Maybe it was that particular evening or maybe it was just the venue, with its inherently throwback vibe, that attracted the people who were present. From where I was standing—a classically journalistic, fly-on-the-wall point of view for this decidedly un-journalistic, essay-profile hybrid—the recording devices took the night off. Then I remembered something Westerman had said: “I think a general culture of immediacy is bad for music. You just have to accept the environment you are presented though and try and effectively put your point across in the best way you can and hope people will respond.”

“Confirmation” was the last song. I hurried downstairs for a different perspective. Did the people listening intently know that Westerman studied philosophy? Or that he was thought to be “lazy” by schoolteachers until he was diagnosed with ADHD? Or that the song they were listening to is one brilliant product of one grim year? How many of the people here, purposefully listening and looking up at the stage, were also looking inwards to confirm that sadness can be regenerative?

For more information, please visit WestermanOfficial.com. Westerman opens for Nilüfer Yanya at the Centre for Contemporary Arts, Glasgow, on April 4.

- By

- Janelle Anne

- Photography by

- Julien Tavel

- Styling by

- Laetitia Paul

Grooming by Philippe Miletto. Photographer’s assistants: Andrei Topli and Theodora Papanikita. Production assistant: Amanda Merlo. Postproduction by Art Post.