JC LEE'S 'LUCE'

Young couples unsure about the prospect of starting a family have not found much comfort this year at LCT3, Lincoln Center Theater’s showcase for young writers. Luce, the company’s latest production, takes on the trying teenage years just months after Daniel Pearle’s sharp A Boy Like Jake tackled the anxieties faced by a couple whose toddler son fantasizes about being a Disney princess. Playwright JC Lee, in his New York début, offers up a liberal-minded husband and wife are forced to reconsider their image of their adopted son, Luce, after he writes a disturbing essay for a class assignment. The bounds of their loyalty are tested, and the inevitable and endless question of how well we can ever know one other—even, or perhaps especially, family—comes to the fore, and is left uncomfortably unanswered.

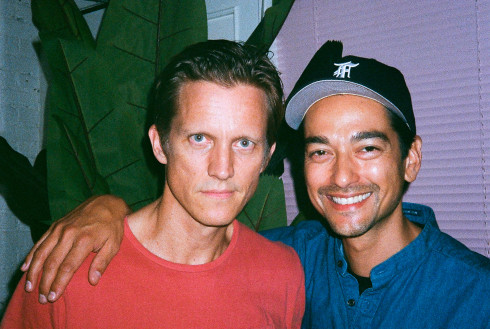

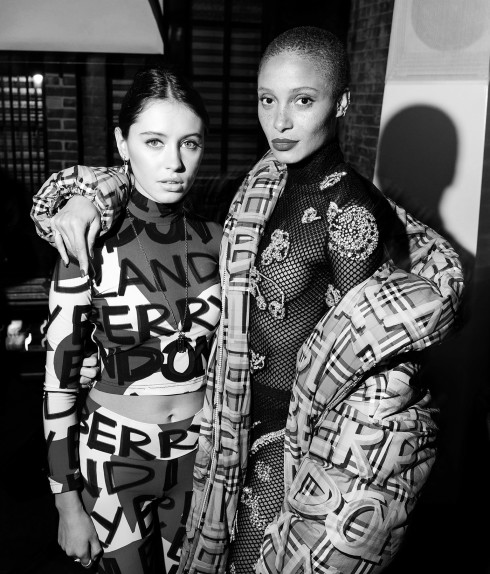

The play’s plot centers around a conflict between Luce, who was adopted from war-stricken Congo as a child, and Harriet, his world cultures teacher. Harriet deems Luce a threat after he takes the position of a violent Eastern European nationalist for a paper in which students were asked to embody a figure from history. Okieriete Onaodowan imbues Luce with a hidden menace cloaked in charm that, as with so many things in this subtle and shifting play, rejects easy interpretation. That question of interpretation, of the impossibility of ever really seeing from someone else’s perspective rather than one’s one, is a driving force of Luce. Luce’s mother Amy struggles to first understand and then comprehend the tension between her son and his professor, but it soon become clear that, although she hears, she doesn’t seem to listen. Her clearer-eyed husband Peter, on the other hand, begins to wonder whether their son is not the boy they think. There are obvious biases at work in all directions, and one of the pleasures of this nuanced play is that it refuses, much like life, to resolve its debates with any conclusive results.

The issue of identity and the debate over nature vs. nurture are perhaps inevitable in any work that touches on the subject of adoption, especially when the difference in environments is as vast as that between Congo and upper-middle-class suburban America, where Luce now lives. Luce, who seems in most respects to have moved beyond the cruelties of his youth, has a precocious self-awareness that allows him to recognize that he is, to many of those around him, less a person than a paragon, a shining example of all that the West can, and must, do to “save” the less-fortunate. Luce greets this reality with surprising equanimity, largely accepting the part he must play as a role model, although the pressure goes some way towards explaining his behavior. He is referred to several times as a top student and a sports star, praises that always seem to carry an unspoken “especially considering…,” a caveat that drags heavily. Harriet, who is African-American, adds the additional burden of calling upon Luce to overcome the stereotypes accorded to him by his race. Lee offers up an honest portrait of a boy who seems to have given up on shouldering the weight forced upon him.

But Luce is also, dense matters of identity and perception aside, a pure family drama, of the sort that pits husband against wife and father against son. Adolescence is an age of writing—and rewriting—the self, often in opposition to one’s parents, and Luce understandably struggles with coming into his own more than the average angsty teen. Theater is full of stories of trouble children, many of them much worse than Luce, but few are as honestly ambiguous as Luce. None of the adult characters is without flaw, and it becomes difficult by the end to categorize any of them as either “right” or “wrong.” Instead, the issue of their goodness is one that twists and sways, never clarifying, only fading away on a dissonant chord that resounds with truth.

Luce runs through November 17 at the Claire Tow Theater, Lincoln Center, New York. Photography by Jeremy Daniel.

Jonathan Shia is the editor of The Last Magazine.