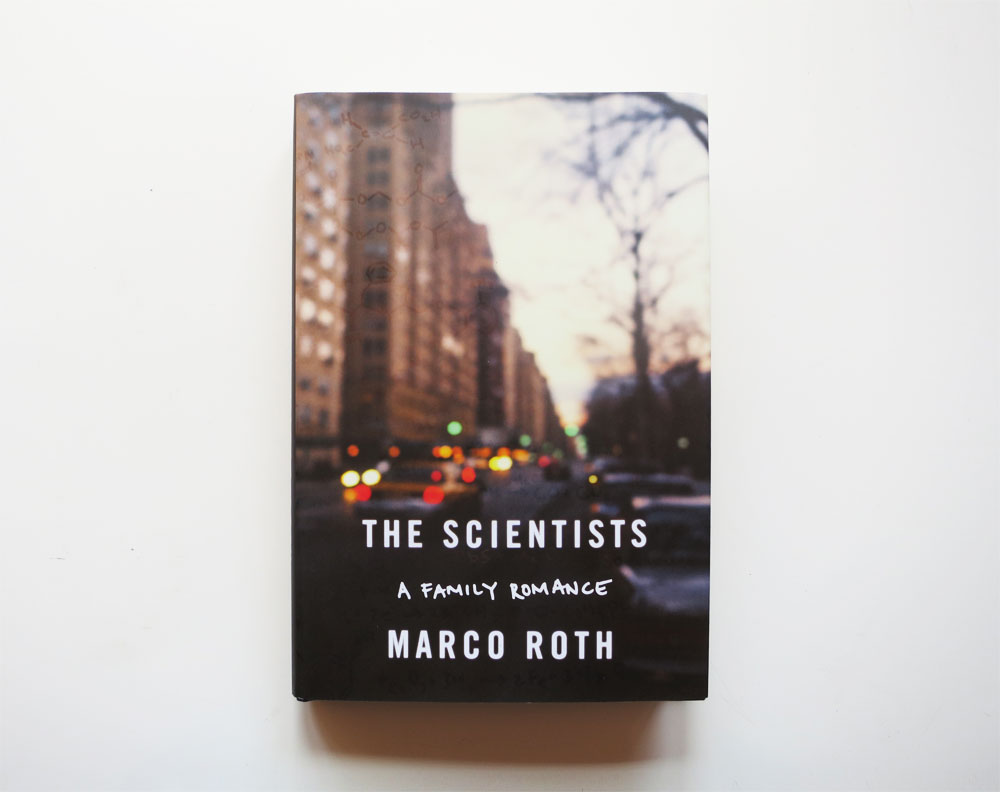

MARCO ROTH'S 'THE SCIENTISTS'

The subtitle of Marco Roth’s memoir—”A Family Romance”—suggests a love story, perhaps the tale of his mother’s devotion as his father wastes away from AIDS, or the crushing legacy of his grandfather’s marriage-for-money, or his own recent divorce. And while all these various and tumultuous affairs do make appearances in The Scientists, the book reveals itself, at heart, as a romance of an altogether different sort, like one from medieval times, with a knight-errant in the starring role and a quest for truth and selfhood at its heart that is no less heroic and epic for its quiet, quotidian nature.

The somewhat-obscure literary allusion is an apt one for Roth, co-founder of the learned review n+1 and an author and editor who describes himself as having been raised in the vanishing middle-class Jewish intellectual milieu of the Upper West Side in the later decades of the twentieth century. His mother, a former classical pianist, and his father, a hematologist with a penchant for existential Russian novels and chamber music, raised him on Norse mythology, Shakespeare’s history plays, and La Fontaine’s fables—in the original French of course. This idyllic childhood comes crashing down when Roth père reveals he has contracted HIV through an accident at his laboratory and begins his slow decline.

Roth makes the typical feints at rebellion during his adolescence, attending Oberlin against the wishes of his parents and fleeing to Guadalajara over winter break rather than returning home, but seems to recognize that his independence is a false front. In a genre overrun with stories of “finding oneself,” Roth acknowledges that perhaps, for a while, he didn’t: “I sensed I was failing at that very American thing, ‘becoming an individual.'”

Years after his father’s death, Roth receives a galley copy of 1185 Park Avenue, his aunt Anne Roiphe’s own memoir, in which she suggests that her brother—Roth’s father—was gay and became infected with HIV in a much more typical manner. That revelation, which is neither confirmed nor denied by Roth’s mother, launches the second half of The Scientists, which finds Roth rereading some of his father’s favorite novels—Thomas Mann’s novella Tonio Kröger, Fathers and Songs, Goncharov’s Oblomov—in a search for insight. A graduate student in comparative literature for many years, he attempts a textual analysis of his father through these works, passed down to him and glancingly digested during his teenage years, but the end is, as it must be, pure speculation. Personal writing is no stranger to the long-hidden familial secret, and it would be facile to say that one of the themes here is the idea that our closest loved ones are sometimes the most inscrutable, but Roth makes a convincing case that we are all, in the end, unknowable, even—and sometimes most glaringly—to ourselves.

If the basic plot points of The Scientists are common ones—the childhood death of a parent, the struggle for self through the early twenties, domestic dramas and broken families—the conceit is one of vigorous originality. For a scholar as avid as Roth, perhaps there is no better way to understand someone than through his literary choices, whether they be lurid genre novels or thorny Barthelme stories. Literature is, in his eyes, a way to learn how to answer the question asked by Sheila Heti’s polarizing book How Should a Person Be? “We first become ourselves,” Roth writes, “by becoming someone else.”

Marco Roth’s The Scientists is out now from Farrar, Straus and Giroux.