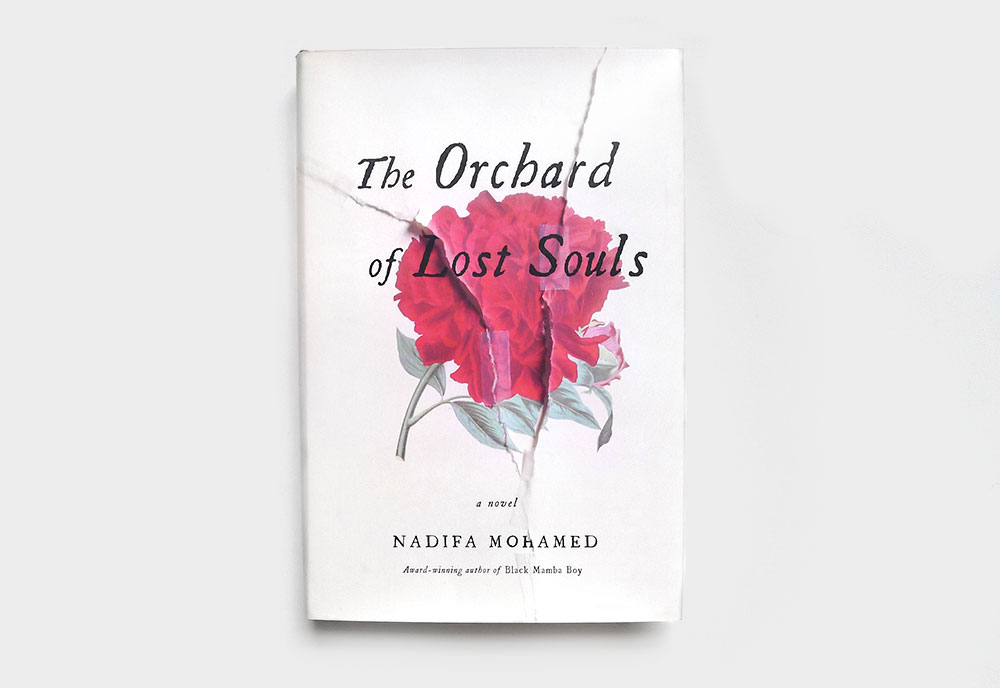

NADIFA MOHAMED'S 'THE ORCHARD OF LOST SOULS'

In Nadifa Mohamed’s intimate and powerful second novel, The Orchard of Lost Souls, the year is 1988, and Somalia is on the brink of civil war. We may remember the scenes ourselves, having watched them flash across our television screens—a scorched landscape ravaged by conflict, a people torn apart by violence—but the lenses of history and journalism panned too wide and too quickly, blurring an entire population into a single, suffering mass. Military dictator Mohamed Siad Barre came into power in a bloodless coup in 1969, and though at first “the shine of independence had made everything magical,” as Mohamed writes, a series of ruinous wars with neighboring countries left “the fury of humiliated men blowing over the Haud desert,” sowing dissent and discontentment among the Somalian people. The civil war was so sprawling, however, that Mohamed decided to focus her intentions for her novel “not on what happened, but to whom it happened,” she says.

Where her first book, Black Mamba Boy, was based on the early life and travels of her father through post-Mussolini East Africa and Europe, The Orchard of Lost Souls was largely inspired by memories, both tender and violent, of her childhood in Hargeisa. Her novel traces the intertwining stories of three women abruptly brought together by a violent confrontation: the widow Kawsar is savagely beaten by Filsan, a young soldier, for trying to protect Deqo, a refugee child. After this initial encounter, each of the characters tells her own story, and as their narratives unfold, the world around them is revealed through Mohamed’s lyrical prose—often with stark, brutal intensity.

“I remember the way children acted out the adult conflict in the local neighborhood, organizing fights between two-year-olds and inflicting immense violence on each other in schools,” she says. But even though the world she describes doesn’t seem to have “space for anything but silence and disobedience,” its great capacity for compassion is revealed as well. “I also have gentler memories about the elderly women I was surrounded by and who were my earliest friends,” Mohamed says; the titular orchard was actually inspired by the one owned by her grandmother. “When I went to visit her orchard in 2008, it was a ruin, full of weeds and rubbish, and her house was still land-mined. That scene really brought home to me all that we had lost and how all the care and effort Somali women had put into nurturing life, even that of plants, had gone to waste.”

Mohamed’s memories, combined with personal testimonies from her extended family, helped give life to her characters, but the intimacy she achieves in her writing hints at a deeper involvement. “My family only left Hargeisa two years before the war broke out, and I kept asking myself, ‘What would I have seen or felt if we had remained there?’ I also wanted to immerse myself in the inner life of these characters and imagine myself into their skin.” In doing so, she gives voice to nine-year-old Deqo, street child and dreamer, who sleeps in a kerosene-soaked barrel but manages to see the “emeralds and sapphires of a peacock’s tail flashing on its moonlit surface,” and she has just as much empathy for the aging, demoralized Kawsar, who dreams only of “the perfect revenge of the old on the thoughtlessly young.”

Yet despite the looming war, it’s the personal battles that take center stage–most prominently, that between women and the relentless shame that “grows and widens with their breasts and hips and follows them like an unwanted friend.” In Somalia, as in the West, “the fear of female bodies and their perceived sexuality is widespread,” Mohamed says, and this fear is manifested even in young Deqo, who is aware that avoiding shame is “at the heart of everything in a girl’s life.” Filsan, too, striving for respect within Barre’s army, realizes that “even in her uniform, they see nothing more than breasts and a hole.” It’s this violation of personhood—the feeling of dehumanization—that is most harshly conveyed in this novel, and it’s perhaps the most painful reality to accept.

Though their individual situations are bleak, the characters eventually find solace, however unexpected, in each other, accepting that “both danger and sanctuary is to be found amongst people.” It’s this ability—to recognize the possibility for tenderness in such hostile circumstances—that makes Mohamed’s work so moving, a factor that likely played a part in her selection as one of Granta’s Best of Young British Novelists in 2013. Her ideas for future work lie with Somali characters, but in a very different setting—one that she has an equally complex relationship with. “I’m fascinated by London and its stories at the moment,” she says, “its divisions, its conflicts, its wealth, and its poverty.” Given her talent for mining the hardest of places for the soft heart within, we look forward to the stories she’ll tell next.

The Orchard of Lost Souls is out now from Farrar, Straus and Giroux.