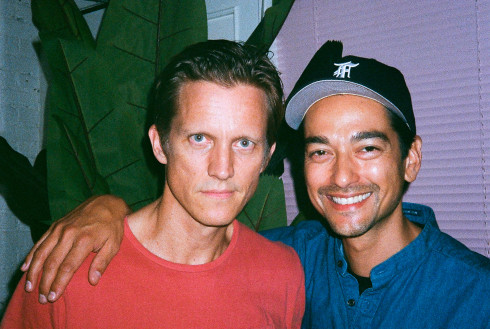

ONLINE EXCLUSIVE: JARED MOSHÉ

When is a Western not a Western? That’s the question Jared Moshé, the young director of Dead Man’s Burden, a neo-Western which opened on Friday, has been playing with lately. The movie’s dusty vistas, set in New Mexico and in period costume, might seem like more of the same—either a John Wayne spoof or a Tarantino bloodbath—but Moshé, a first-time director and writer, is earning high praise for a reason. “I’m interested in mythology, and the West is the mythology of America,” he says.

Dead Man’s Burden walks a fine line, blending elements of noir with post-Civil War cowboys and a cinematic eye built around lush set pieces. It’s hard to make a Western that feels exciting, let alone on a tight budget, but it’s a gamble that is paying off. “I like to sort of joke when I talk to people,” Moshé says from Nashville, a day before Dead Man’s Burden is set to screen at the Nashville Film Festival. “When is a film not a film? When is a Western not a Western? There is this bias against the genre that people don’t necessarily ask about other genres. There are a million relationship dramas made—how do you add something to that? There are a billion action movies made—how do you add something to that? Where you can modernize a Western is in the characters and the story. Modern audiences want more sophisticated characters, to get into the heads of people that audiences maybe fifty years ago did not.”

The story of Dead Man’s Burden is purposely abstruse, centered around the kind of family betrayal that doesn’t end well. The movie begins with a shot: Martha, played by Clare Bowen, kills her father, shooting him as he rides off on horseback. The rest of the film is spent untangling a messy lie. Martha and her husband (David Call), are feral animals trying to sell off a stretch of land to a mining company as a way to buy a better life. But Martha’s brother (Barlow Jacobs), once thought dead in the Civil War, returns to uncover what became of his father and his inheritance.

For a film with much to tell, Moshé is stoically alert to the space between Dead Man’s Burden’s characters. “I had to think as much about what people say as much as what they don’t say,” he says. “I had to put myself in the situation of what it was like to be out in the middle of nowhere with the same people, day in and day out, and how there’d be a different way of communicating.”

Moshé grew up in Chappaqua, New York, the only son of Greek-Jewish doctor and a journalist mother, and was involved in film through much of his early life. After earning a bachelor’s in English from Amherst, he worked with several small-scale studios as a development assistant and sales associate, finally working his way up to produce films including Silver Tongues, Kurt Cobain: About a Son, Low & Behold, Beautiful Losers, and Corman’s World: Exploits of a Hollywood Rebel. “As a producer, your job is to figure out how to make someone else’s vision a realty,” Moshé says.

Having spent ten years helping other people realize their visions, Moshé felt it was time to share his own. “I love this industry and I think I have a voice that I want to express,” he says. Dead Man’s Burden may seem like a stock choice, but it was the perfect way for Moshé, a self-professed history buff, to address the gray areas and moral ambiguity that plague America. “I think we’re in a very divisive time in the country,” he says. “There’s a lot of yelling and a lot ideology, a lot of people not being able to see past their own ideas. I want to tell a story about that, about the cost of ideology, and ask if people can stop thinking about these concepts and actually see how those ideas affect real people.”

Dead Man’s Burden plays with such ethical uncertainties. Bad guys aren’t all bad, and questions have many answers. While most reviews have lauded the film for its economy and complexity, it is also downright beautiful. New Mexico is a sublime canvas in Moshé’s hands, with help from director of photography Rob Hauer. The film seems set in a perpetual sundown. Rays of light wrap around Moshé’s handsome actors or sprawl over the plains and mountains of the film’s setting.

New Mexico becomes a supporting character in Dead Man’s Burden. Every scene is set outdoors save one in the second act. The landscape breathes, as much a player in the plot as the family making its way across it. “Going out to make a Western is like living a Western,” Moshé says. “When you’re shooting on location in the middle of the desert in New Mexico, anything can happen. It brings the cast and crew together in a certain way.”

Moshé wrote the script for Dead Man’s Burden in six weeks, and began shooting only five months later. He hasn’t stopped hustling since. Fresh off the festival circuit, he’s currently at work promoting the limited theatrical release. There are other projects on the horizon for Moshé—a TV pitch about private military contractors and another film set on the frontier—but this labor of love is Moshé’s current burden, and one he gladly bears.

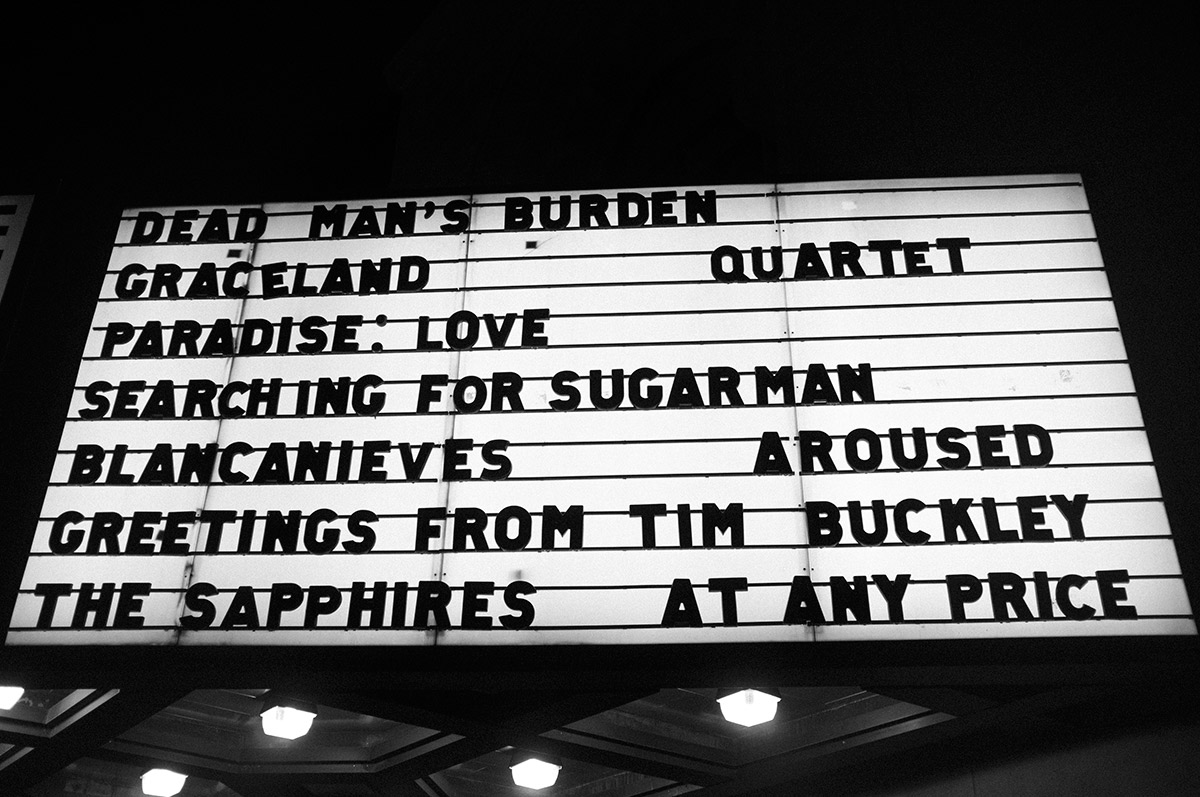

Dead Man’s Burden is currently playing at Village East Cinemas, 181-189 Second Avenue, New York.